'Give us back our gods': Inside Nepal's Museum of Stolen Art

One of the 45 replicas in Rabindra Puri's museum

- Published

Along a small street in Nepal's Bhaktapur city stands an unassuming building with a strange name - the Museum of Stolen Art.

Inside it are rooms filled with statues of Nepal's sacred gods and goddesses.

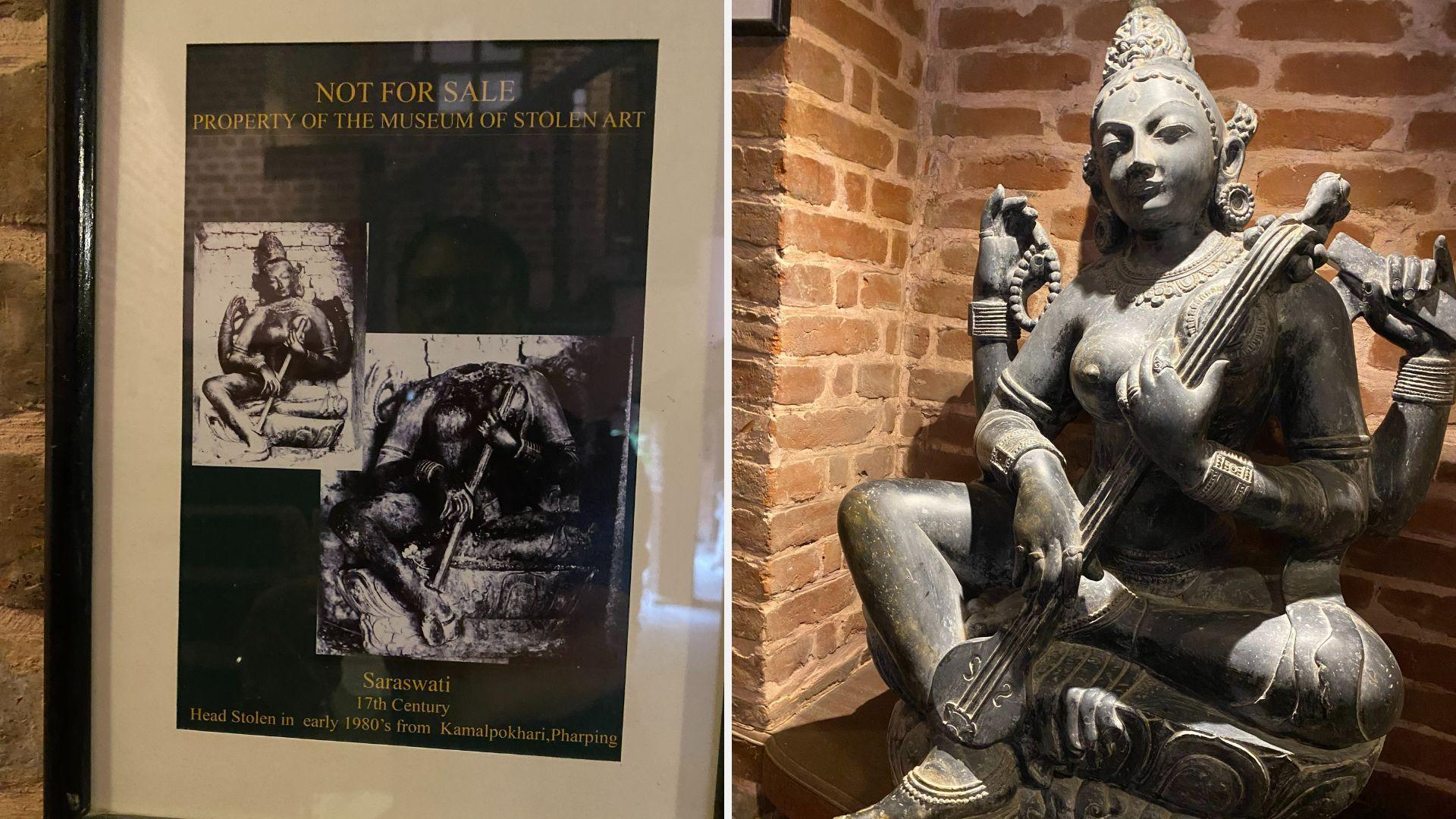

Among them is the Saraswati sculpture. Sitting atop a lotus, the Hindu goddess of wisdom holds a book, prayer beads and a classical instrument called a veena in her four hands.

But like all the other sculptures in the room, the statue is a fake.

The Saraswati is one of 45 replicas in the museum, which will have an official site in Panauti, set to open to the public in 2026.

The museum is the brainchild of Nepalese conservationist Rabindra Puri, who is spearheading a mission to secure the return of dozens of Nepal's stolen artefacts, many of which are scattered across museums, auction houses or private collections in countries like the US, UK and France.

In the past five years, he has hired half a dozen craftsmen to create replicas of these statues, each taking between three months and a year to finish. The museum has not received any government funding.

His mission is to secure the return of these stolen artefacts - in exchange for the replicas he has created.

In Nepal, such statues reside in temples all across the country and are regarded as part of the country's "living culture", rather than mere showpieces, says Sanjay Adhikari, the secretary of the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign.

Many are worshipped by locals every day, with some followers offering food and flowers to the gods.

“An old lady told me she used to worship Saraswati daily,” says Mr Puri. “When she found out the idol was stolen, she felt more depressed than when her husband passed away.”

It is also common for followers to touch these statues for blessings - meaning they are also rarely guarded - leaving them wide open for thieves.

A replica of a Saraswati idol - the original was mutilated and its head stolen (left photo)

Nepal has categorised more than 400 artefacts missing from temples and monasteries across the country, but the number is highly likely to be an underestimate, says Saubhagya Pradhananga, who heads the official Department of Archaeology.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, hundreds of artefacts were looted from Nepal as the isolated country was opening up to the outside world.

Many of the country's most powerful administrators back then were believed to have been behind some of these thefts - responsible for smuggling them abroad to art collectors and pocketing the proceeds.

For decades, Nepalis were largely unaware about their missing art and where it had gone, but that has been changing, especially since the founding of the National Heritage Recovery Campaign in 2021 - a movement led by citizen activists to reclaim lost treasures.

Activists have found that many of these idols are now in museums, auction houses or private collections in Western countries such as the US, the UK and France.

They also work with foreign governments to pressure overseas institutions to return the pieces.

'Shocked to find it in an American museum'

But there are many hurdles. The Taleju Necklace, dating back to the 17th century, is a case in point.

In 1970, the giant gold-plated necklace engraved with precious stones went missing from the Temple of Taleju - the goddess known as the chief protective deity of Nepal.

Its disappearance was all the more shocking as the temple is only open to the public once a year – on the 9th day of the Dashain Festival.

It's still unclear how it might have been stolen and many in Nepal had no idea where it might have gone until three years ago, when it was seen in an unlikely place - the Art Institute of Chicago.

It was spotted by Dr Sweta Gyanu Baniya, a Nepali academic based in the US who said she fell to her knees and started to cry when she saw the necklace.

"It's not just a necklace, it's a part of our goddess who we worship. I felt like it shouldn't be here. It's sacred," she told the US university Virginia Tech.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

“We were shocked to learn after so many years that it was on display in an American museum,” says Uddhav Karmacharya, the chief priest of the Temple of Taleju.

He has submitted documents proving its provenance to Nepali authorities, saying: "The day it is repatriated will be the most important day in my life."

According to the Art Institute of Chicago, the necklace is a gift from the Alsdorf Foundation - a private US foundation. The museum told the BBC it has communicated with the Nepali government and is awaiting additional information.

But Pradhananga said Nepal's Department of Archaeology had provided enough evidence, including archival records. On top of that, an inscription on the necklace says it was specifically made for the Goddess of Taleju by King Pratap Malla.

It's these "tactics of delay" that often "wear down campaigners", says one activist, Kanak Mani Dixit.

“They like to use the word ‘provenance’ whereby they ask for evidence from us. The onus is put on us to prove that it belongs to Nepal, rather than on themselves on how they got hold of them.”

But overall, some progress has been made, and about 200 artefacts have been returned to Nepal since 1986 – though most transfers took place in the past decade.

An idol representing the deities Laxmi and Narayan - a husband and wife duo - has been brought back home to Nepal from the Dallas Museum of Art almost 40 years after it first disappeared from a temple.

Currently, 80 repatriated artefacts are housed in a special gallery of the National Museum of Nepal, waiting to undergo restoration before being returned to their rightful place. Six idols have been returned to the community since 2022.

Some communities have put the idols in iron cages for security

The idol of Laxmi Narayan has been brought home and reinstalled at the temple it was originally taken from and is being worshipped daily, just like it was in the 10th Century when the idol was first made.

But many worshippers are now a lot more paranoid - putting these idols in iron cages to protect them from going missing.

Mr Puri however hopes his museum will eventually have its shelves wiped bare.

“I want to tell the museums and whoever is holding the stolen artefacts: Just return our gods!” he says. “You can have your art.”