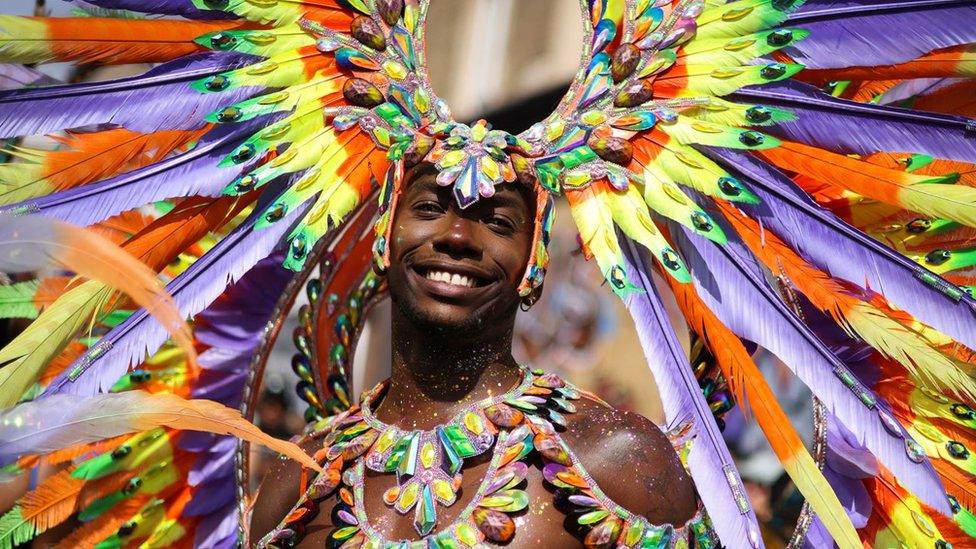

Curry, chutney and the Notting Hill Carnival

Parbatee Sawh, who goes by Sarah, and her daughter Christina sell Trinidadian food at Notting Hill Festival

- Published

In a small kitchen hidden away in west London, Parbatee Sawh, who goes by the name Sarah, is frying dough to make doubles, a popular Trinidadian snack of flatbread filled with curried chickpeas.

It's the kind of dish she's previously made for the Notting Hill Carnival and indeed claims to be one of the first to introduce Indo-Caribbean cuisine to the event.

"I started selling rotis, aloo pie, dhal puri… just out of my car," she says with a smile. "Then in the 90s I started distributing my Indo-Caribbean cuisine to the yearly event."

Originally from Trinidad, Sarah moved to Lewisham in 1972 to work as a nurse. Since then, she has become a regular at Carnival, serving up meals that reflect her heritage.

"I had noticed there was a real lack of Trinidadian food, even though the carnival has its roots in Trinidad," she explains.

"The Indian influence in some of the dishes reflects the island's diverse cultural heritage."

Doubles are a common street food of Indo-Trinidadian origin that consist of curried chickpeas served on two fried flatbreads

These days, Sarah's daughters Christina and Leah Bedeau do most of the cooking for their stall Sweet Hand Cuisine, though the 72-year-old still gets involved.

"Caribbean cuisine is incredibly diverse," says Christina, whose father is from Grenada.

Growing up in west London, the 38-year-old says she often found her mixed Black-Indian identity hard for others to place - especially compared to visits back to Trinidad.

"In London during the 90s, there wasn't really a space for Indo-Caribbeans. People didn't know how to box me, and I'd get frowned upon by different ethnic groups, whereas in Trinidad the diversity is the norm," says Christina.

She also feels that while the food is loved, the deeper history is often overlooked.

"People don't always talk about how Indians came to the Caribbean in the first place. There isn't much awareness of indentureship. The dishes get celebrated, but the story behind them does not," she says.

Sophia says she connects to her heritage through Notting Hill Carnival

It's a perspective shared by Sophia Estelle Mangroo, who is another regular at Notting Hill Carnival.

"As a second-generation British Indo-Trinidadian whose grandparents came to the UK during the Windrush era, a moment often portrayed as Afro-Caribbean, I think it's vital to acknowledge that Indo-Caribbeans were part of that journey too."

Hailing from Tooting, she enjoys raising awareness of the Indo-Caribbean culture in London through her social media.

"I attend Carnival because it connects me to my heritage through music, dance and celebration," she adds.

Pholourie, a fried Indo-Caribbean snack food commonly eaten in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname and other parts of the Caribbean.

An Indo-Caribbean music genre called chutney is also often played at Notting Hill Carnival, which according to Sophia, some people do not realise is an Indo- Caribbean rhythm.

The British Journal of Ethnomusicology , externaldescribes chutney as a vibrant fusion that blends Indian folk music with Caribbean calypso and soca.

But behind these lively rhythms and delicious dishes lies a deeper, often untold history of indentureship.

The Caribbean has always been a melting pot of culture and history. Among the African, Chinese and European waves of migration came the Indian populations.

A project by the National Archives highlighted how it started, external following the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, when the British Empire turned to India for cheap labour.

Between 1838 and 1917, more than half a million Indians were brought to work on sugar cane plantations across the British colonies, external.

Most came from northern India; Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal.

They signed contracts to work for three to five years in exchange for wages and, later, the choice between a return passage to India or land and citizenship.

Their journeys were long and often dangerous, with months spent in overcrowded ships under harsh conditions.

Many eventually settled in the Caribbean, in countries like Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Suriname, and formed tight-knit communities that preserved elements of Indian culture while they adapted to their new homes.

Same dish, different sides of the world

Christina recalls a moment when she met someone from Mauritius at a community event in London.

"We both sat down with dhal puri and just laughed. Same dish, similar taste, but our parents had grown up on different sides of the world," she says.

According to writer and indentureship expert Gina Agnew, who is of Indo-Guyanese descent, this shared culinary heritage is no coincidence.

"Dhal puri, a flatbread made with seasoned ground chickpeas, was born out of necessity," she explains.

"It was created by indentured workers during the voyage itself. So you'll find versions of this dish not just in the Caribbean, but in places like Mauritius, Fiji, and South Africa - wherever Indians were taken under indentureship."

The Indo-Caribbean story did not end in the Caribbean.

From the 1950s onwards, many Indo-Caribbean families, particularly from Trinidad and Guyana, migrated to the UK as part of the wider post-Windrush movement.

Encouraged to settle in Britain to help rebuild the country following World War Two, they arrived with hopes for better opportunities.

London quickly became a hub, with communities forming in areas including Ladbroke Grove, Southall, Harlesden and Brixton, bringing their food, music and culture with them.

It is in these neighbourhoods where the seeds of Notting Hill Carnival were also planted, and where the sounds and smells of Indo-Caribbean culture, such as sizzling doubles, still fill the streets today.

Sarah says she began distributing her Indo-Caribbean cuisine, including Dhal Puri, at Notting Hill Carnival in the 1990s

As of 2021, there are an estimated 2.5 million people of Indo-Caribbean descent worldwide, Gina says.

In countries like Guyana and Trinidad, they represent up to 40% of the population and are the largest ethnic group in some areas.

Indian influence is deeply woven into the cultural fabric: from chutney music to dishes like dhal puri and chicken curry - or curry chicken, depending on who you ask - to festivals like Phagwah (Holi) and Indian Arrival Day.

Gina, who was involved in the National Archives project on indentured workers in 2023, notes that many descendants still struggle to trace their roots.

"A lot of families simply don't know where in India their ancestors came from, but that's slowly changing," she says.

For Sarah, her daughters and Sophia, Notting Hill Carnival is not just about the food, music, or costumes - it is about honouring a legacy that spans continents, generations, and the resilience of people who made the Caribbean - and later London - their home.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published20 August

- Published21 March 2024