Listen to Fergal read this article

Every single person in his platoon knew someone who was killed. Yuval Green, 26, knew at least three. He was a reservist, a medic in the paratroops of the Israel Defence Forces, when he heard the first news of the 7 October Hamas attack.

“Israel is a small country. Everyone knows each other,” he says. In several days of violence,1,200 people were killed, and 251 more abducted into Gaza. Ninety-seven hostages remain in Gaza, and around half of them are believed to be alive.

Yuval immediately answered his country’s call to arms. It was a mission to defend Israelis. He recalls the horror of entering devastated Jewish communities near the Gaza border. “You're seeing… dead bodies on the streets, seeing cars punctured by bullets.”

Back then, there was no doubt about reporting for duty. The country was under attack. The hostages had to be brought home.

Then came the fighting in Gaza itself. Things seen that could not be unseen. Like the night he saw cats eating human remains in the roadway.

“Start to imagine, like an apocalypse. You look to your right, you look to your left, all you see is destroyed buildings, buildings that are damaged by fire, by missiles, everything. That's Gaza right now.”

One year on, the young man who reported for duty on 7 October is refusing to fight.

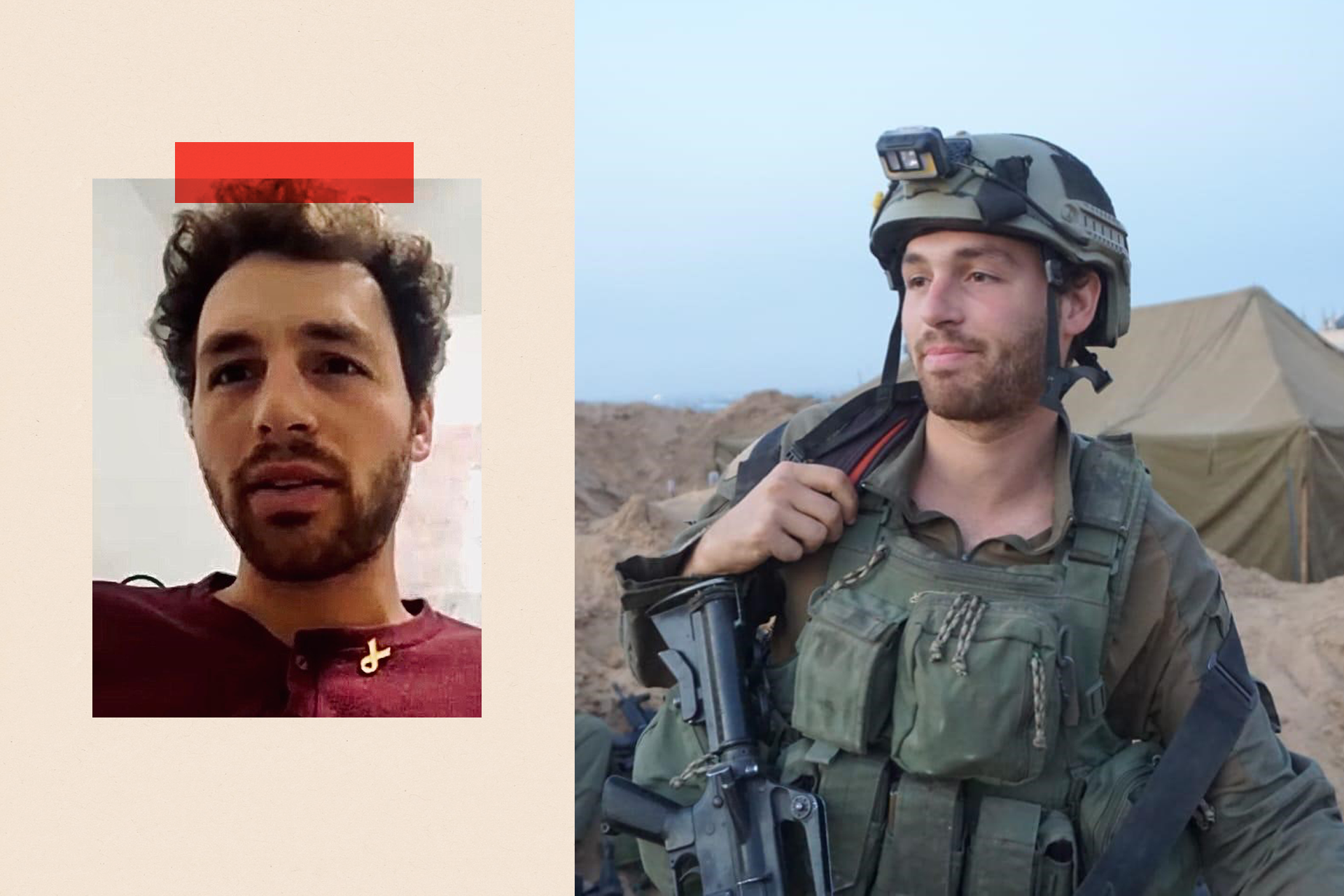

Yuval Green is among those refusing to continue fighting in Gaza

Yuval is the co-organiser of a public letter signed by more than 165 - at the latest count - Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) reservists, and a smaller number of permanent soldiers, refusing to serve, or threatening to refuse, unless the hostages are returned - something that would require a ceasefire deal with Hamas.

In a country still traumatised by the worst violence in its history, those refusing for reasons of conscience are a minority in a military that includes around 465,000 reservists.

There is another factor in play for some other IDF reservists: exhaustion.

According to Israeli media reports, a growing number are failing to report for duty. The Times of Israel newspaper and several other outlets quoted military sources as saying that there was a drop of between 15% to 25% of troops showing up, mainly due to burnout with the long periods of service required of them.

Even if there is not widespread public support for those refusing to serve because of reasons of conscience, there is evidence that some of the key demands of those who signed the refusal letter are shared by a growing number of Israelis.

A recent opinion poll by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) indicated that among Jewish Israelis 45% wanted the war to end - with a ceasefire to bring the hostages home - against 43% who wanted the IDF to fight on to destroy Hamas.

Significantly, the IDI poll also suggests that the sense of solidarity which marked the opening days of the war as the country reeled from the trauma of 7 October has been overtaken by the revival of political divisions: only 26% of Israelis believe there is now a sense of togetherness, while 44% say there is not.

At least part of this has to do with a feeling often expressed, especially among those on the left of the political divide, that the war is being prolonged at the behest of far-right parties whose support Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu needs to remain in power.

Reports suggest a decline in Israeli soldiers reporting for duty

Even the former Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, a member of Netanhayu’s Likud Party, dismissed by the prime minister last month, cited the failure to return the hostages as one of the key disagreements with his boss.

“There is and will not be any atonement for abandoning the captives,” he said. “It will be a mark of Cain on the forehead of Israeli society and those leading this mistaken path.”

Netanyahu, who along with Gallant is facing an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court for alleged war crimes, has repeatedly denied this and stressed his commitment to freeing the hostages.

The seeds of refusal

The seeds of Yuval’s refusal lie back in the days soon after the war began. Then the deputy speaker of the Knesset (Israel’s parliament), Nissim Vaturi, called for the Gaza Strip to be “erased from the face of the Earth”. Prominent rabbi Eliyahu Mali, referring generally to Palestinians in Gaza, said: “If you don’t kill them, they’ll kill you.” The rabbi stressed soldiers should only do what the army orders, and that the state law did not allow for the killing of the civilian population.

But the language - by no means restricted to the two examples above - worried Yuval.

“People were speaking about killing the entire population of Gaza, as if it was some type of an academic idea that makes sense… And with this atmosphere, soldiers are entering Gaza just a month after their friends were butchered, hearing about soldiers dying every day. And soldiers do a lot of things.”

There have been social media posts from soldiers in Gaza abusing prisoners, destroying property, and mocking Palestinians, including numerous examples of soldiers posing with people’s possessions - including womens’ dresses and underwear.

“I was trying to fight that at the time as much as I could,” says Yuval. “There was a lot of dehumanising, a vengeful atmosphere.”

Thousands of Palestinians have fled their homes

His personal turning point came with an order he could not obey.

“They told us to burn down a house, and I went to my commander and asked him: ‘Why are we doing that?’ And the answers he gave me were just not good enough. I wasn't willing to burn down a house without reasons that make sense, without knowing that this serves a certain military purpose, or any type of purpose. So I said no and left.”

That was his last day in Gaza.

In response, the IDF told me that its actions were “based on military necessity, and with accordance to international law” and said Hamas “unlawfully embed their military assets in civilian areas”.

Three of the refusers have spoken to the BBC. Two agreed to give their names, while a third requested anonymity because he feared repercussions. All stress that they love their country, but the experience of the war, the failure to reach a hostage deal led to a defining moral choice.

'People calmly talked about abuse or murder'

One soldier, who asked to remain anonymous, was at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion airport when news started coming in about the Hamas attacks. He recalls feeling shock at first. Then a ringing sensation in his ears. “I remember the drive home… The radio’s on and people [are] calling in, saying: ‘My dad was just kidnapped, help me. No-one's helping me.’ It was truly a living nightmare.”

This was the moment the IDF was made for, he felt. It wasn’t like making house raids in the occupied West Bank or chasing stone-throwing youths. “Probably for the first time I felt like I enlisted in true self-defence.”

But his view transformed as the war progressed. “I guess I no longer felt I could honestly say that this campaign was centered around securing the lives of Israelis.”

Tributes at the Nova festival site

He says this was based on what he saw and heard among comrades. “I try to have empathy and say, ‘This is what happens to people who are torn apart by war…’ but it was hard to overlook how wide this discourse was.”

He recalls comrades boasting, even to their commanders, about beating “helpless Palestinians”. And he heard more chilling conversations. “People would pretty calmly talk about cases of abuse or even murder, as if it was a technicality, or with real serenity. That obviously shocked me.”

The soldier also says he witnessed prisoners being blindfolded and not allowed to move “for basically their entire stay… and given amounts of food that were shocking”.

When his first tour of duty ended he vowed not to return.

The IDF referred me to a statement from last May which said any abuse of detainees was strictly prohibited. It also said three meals a day were provided, “of quantity and variety approved by a qualified nutritionist”. It said handcuffing of detainees was only carried out “where the security risk requires it” and “every day an examination is carried out… to make sure that the handcuffs are not too tight”.

The UN has said reports of alleged torture and sexual violence by Israeli guards were “grossly illegal and revolting” and enabled by “absolute impunity”.

‘A fertile ground for fostering brutality’

Michael Ofer-Ziv, 29, knew two people from his village who were killed on 7 October, among them Shani Louk whose body was paraded through Gaza on the back of a pickup truck in what became one of the most widely shared images of the war. “That was hell,” he says.

Michael was already a committed left-winger who advocated political not military solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But, like his comrades, he felt reporting for reserve duty was correct. “I knew that the military action was inevitable… and was justified in a way, but I was very worried about the shape it might take.”

His job was to work as an operations officer in a brigade war room, watching and directing action relayed back from drone cameras in Gaza. At times the physical reality of the war hit home.

“We went to get some paper from somewhere in the main command of the Gaza area,” he remembers. “And at some point we opened the window… and the stench was like a butchery… Like in the market, where it's not very clean.”

Again it was a remark heard during a discussion among comrades that helped push him towards action. “I think the most horrible sentence that I heard was someone who said to me that the kids that we spared in the last war in Gaza [2014] became the terrorists of October 7, which I bet is true for some cases… but definitely not all of them.”

Michael Ofer-Ziv was an operations officer in brigade war room

Such extreme views existed among a minority of soldiers, he says, but the majority were “just indifferent towards the price… what's called ‘collateral damage’, or Palestinian lives”. He’s also dismayed by statements that Jewish settlements should be built in Gaza after the war - a stated aim of far-right government ministers, and even some members of Netanyahu’s Likud party.

Figures suggest there is a growing body of officers and troops within the IDF who come from what is called a ‘National Religious’ background: these are supporters of far-right Jewish nationalist parties who advocate settlement and annexation of Palestinian lands, and are firmly opposed to Palestinian statehood. According to research from the Israeli Centre for Public Affairs, a non-governmental think tank, the number of such officers graduating from the military academy rose from 2.5% in 1990 to 40% in 2014.

Ten years ago, one of Israel’s leading authorities on the issue, Professor Mordechai Kremnitzer, a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, warned about what he called the ‘religification’ of the army. “Within this context, messages about Jewish superiority and demonisation of the enemy are fertile ground for fostering brutality and releasing soldiers from moral constraints.”

The decisive moment for Michael Ofer-Ziv came when the IDF shot three Israeli hostages in Gaza in December 2023. The three men approached the army stripped to the waist, and one held a stick with a white cloth. The IDF said a soldier had felt threatened and opened fire, killing two hostages. A third was wounded but then shot again and killed, when a soldier ignored his commander’s ceasefire order.

More from InDepth

'I spent 30 years as a therapist to killers - and no-one is born evil'

- Published1 December 2024

Will flights really reach net zero by 2050 - and at what cost to passengers?

- Published29 November 2024

Trump and Xi Jinping’s ‘loving’ relationship has soured - can they rebuild it?

- Published19 November 2024

“I remember thinking to what level of moral corruption have we got… that this can happen. And I also remember thinking, there is just no way this is the first time [innocent people were shot]… It's just the first time that we are hearing about it, because they are hostages. If the victims were Palestinians, we just would never hear about it.”

The IDF has said that refusal to serve by reservists is dealt with on a case-by-case basis, and Prime Minister Netanyahu insists it is “the most moral army in the world”. For most Israelis, the IDF is the guarantor of their security; it helped found Israel in 1948 and is an expression of the nation - every Israeli citizen over 18 who is Jewish (and also Druze and Circassian minorities) must serve.

The refusers have attracted some hostility. Some prominent politicians, like Miri Regev, a cabinet member and former IDF spokeswoman, have called for action. “Refusers should be arrested and prosecuted," she has said.

But the government has so far avoided tough action because, according to Yuval Green, “the military realised that it only draws attention to our actions, so they try to let us go quietly.” For those starting their national service and who refuse, sanctions are tougher. Eight conscientious objectors - not part of the reservists group - due to begin their military service at 18 years old have served time in military prison.

The future character of the Jewish state

The soldiers I spoke with described a mix of anger, disappointment, pain or ‘radio silence’ from their former comrades.

“I strongly oppose them [the refusers],” says Major Sam Lipsky, 31, a reservist who fought in Gaza during the current war but is now based outside the Strip. He accuses the refusers group of being “highly political” and focused on opposing the current government.

“I don't have to be a Netanyahu fan in order to not appreciate people using the military, an institution we're all meant to rally behind, as political leverage.”

Maj Lipsky is a supporter of what he views as Israel’s mainstream right - not the far right represented by government figures like Itamar Ben-Gvir, the national security minister who has been convicted of inciting racism and supporting terrorism, and finance minister, Belazel Smotrich, who recently called for the population of Gaza to be halved by encouraging “voluntary migration”.

Maj Lipsky acknowledges the civilian suffering in Gaza and does not deny the imagery of dead and maimed women and children.

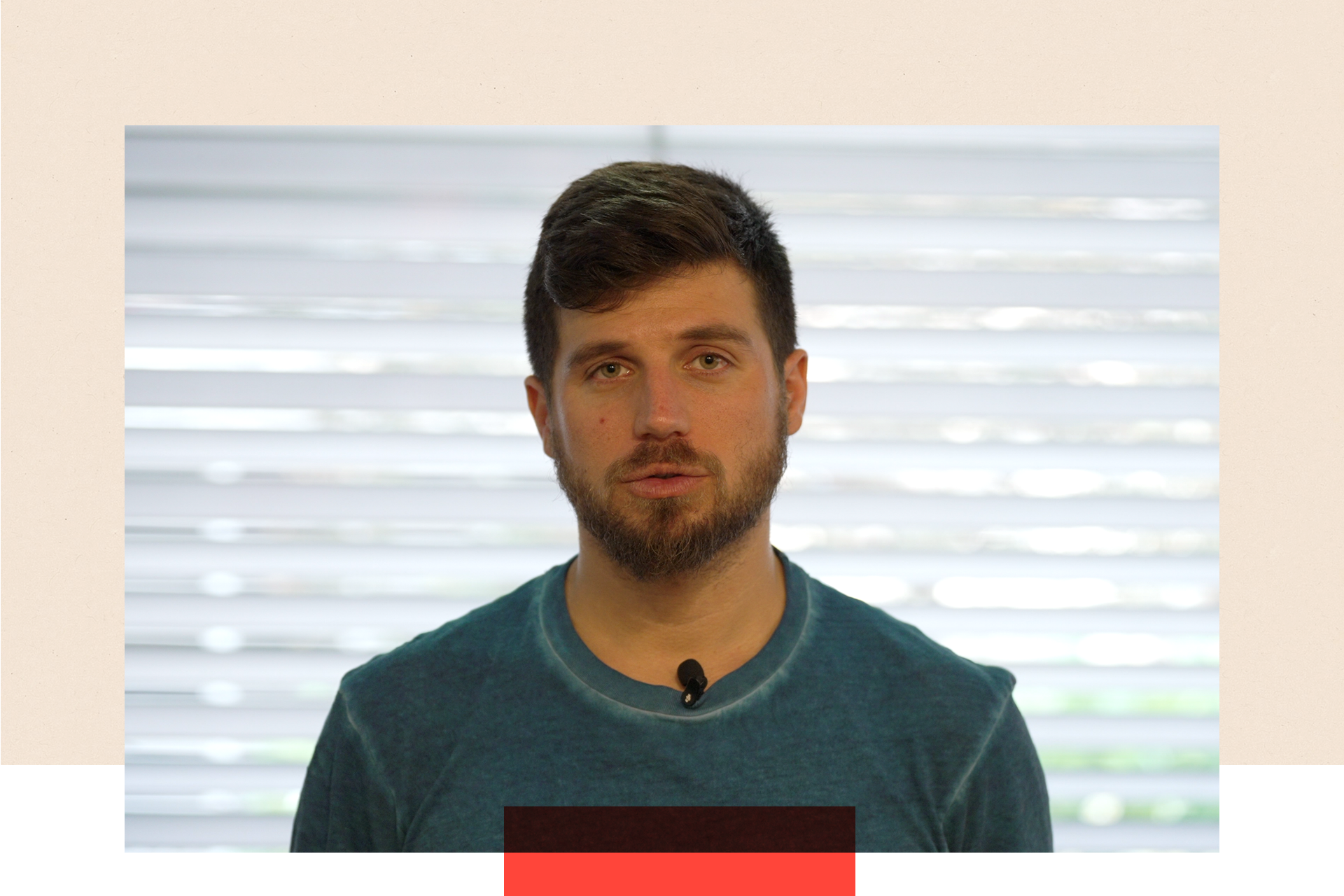

Sam Lipsky, who fought in Gaza during the ongoing conflict, is now stationed outside the Gaza Strip

As we speak at his home in southern Israel, his two young children are sleeping in the next room. “There's no way to fight the war and to prosecute a military campaign without these images happening,” he says. He then uses an expression heard in the past from Israeli leaders: “You can't mow the lawn without grass flying up. It is not possible.”

He says the blame belongs to Hamas who went to “randomly slaughter as many Jews as possible, women, children, soldiers”.

The imperative of fighting the war has postponed a deepening struggle over the future character of the Jewish state. It is, in large part, a conflict between the secularist ideals held by people like Michael Ofer-Zif and Yuval Green, and the increasingly powerful religious right represented by the settlements movement, and their champions in Netanyahu’s cabinet, including figures like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich.

Add to that the lingering, widespread anger over the government’s attempts to dilute the power of the country’s judiciary in 2023 - it led to mass demonstrations in the months before October 7 - and the stage is set for a turbulent politics long after the war ends.

On both sides it is not unusual to hear people talk of a struggle for the soul of Israel.

Maj Lipsky was packing to return to military duty on the evening I met him, sure of his duty and responsibility. No peace until Hamas was defeated.

Among the refusers I spoke with, there was a determination to stand by their principles. Michael Ofer-Ziv may leave Israel, unsure whether he can be happy in the country. “It just looks less and less likely that I will be able to hold the values that I hold, wanting the future that I want for my kids to live here, and that is very scary,” he says.

Yuval Green is training to become a doctor, and hopes that a settlement can be reached between peacemakers among the Israeli and Palestinian people. “I think in this conflict, there are only two sides, not the Israeli side and the Palestinian side. There is the side that supports violence and the side that supports, you know, finding better solutions.” There are many Israelis who would disagree with that analysis, but it won’t stop his mission.

Top image credit: Getty

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Girl who lost eye in Israeli raid that killed father carries ‘pain mountains can't bear’

- Published7 October 2024

What has happened to the leaders of Hamas?

- Published21 January

The Lebanon ceasefire is a respite, not a solution for the Middle East

- Published27 November 2024

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.