Five words that changed the Sara Sharif murder trial

Sara's uncle Faisal Malik, her stepmother Beinash Batool and her father Urfan Sharif all stood trial at the Old Bailey

- Published

On the morning of 13 November, four weeks into the murder trial of 10-year-old Sara Sharif, came a moment so dramatic it left jurors open-mouthed and an Old Bailey courtroom horrified.

Sara’s father Urfan Sharif had not long been in the witness box on the seventh day of giving evidence when suddenly, trembling, he uttered five words that would change the course of the trial.

“She died because of me.”

Until then, he had denied almost everything, instead blaming his wife - Sara’s stepmother - for her death. Now he was suddenly taking full responsibility for his daughter's death.

It was the defining moment of an eight-week murder trial, which was disturbing and heart-breaking for jurors to sit through. They listened to horrifying details of Sara’s short, desperate life - the torture, the beatings, the injuries - and watched the courtroom drama of a husband and wife turning on each other.

Warning: This article contains descriptions of physical abuse

'Too close for comfort'

The trial began just over a year after Sara was found dead in a bunkbed in her home - alone and abandoned by her family.

Inside the glass-panelled dock at London's Old Bailey were the three people accused of her murder; Sara’s father, Urfan Sharif, her stepmother, Beinash Batool, and her uncle, Faisal Malik. They were separated by dock officers but were, I imagined, still too close for comfort.

"There is a head-on conflict brewing between the defendants,” prosecutor Bill Emlyn Jones KC said at the start of the trial.

Sharif was smartly dressed in a white collared shirt and black jacket. He was much thinner than in the pictures we had seen of him. Batool had gold-rimmed glasses on and wore a mustard jacket, with her hair tied back.

In the weeks they spent together in the dock not once did I see the two of them make eye contact. Most of the time they stared ahead. Sometimes they would look down at bundles of evidence.

On days Batool arrived first, her husband would have to walk within inches of her to get to his seat. They never turned to each other and they never spoke.

Both would often cry. The sounds of her sobbing would fill the courtroom. One day proceedings had to be suspended when Sharif, upset, walked out of the dock.

He would go on to brand his wife a “psycho” from the witness box, only to later take it back. One day she called out “liar” while he was giving evidence.

Sara suffered dozens of horrific injuries, the court heard

The first days of the trial were particularly shocking. Sara’s treatment had been brutal, the prosecutor said.

X-rays were put up on screens showing her fractured bones. Computer-generated images showed the extensive bruising over her body. “I’m afraid you may find even the graphical depictions upsetting," the prosecutor told the jury.

Mr Emlyn Jones KC took us through the dozens of horrific injuries, both old and new - fractures and refractures, puncture wounds and abrasions, burns, blisters and bite marks.

There was an injury to Sara’s abdomen and a traumatic injury to her brain.

Just when we thought it could not get any worse there was more disturbing and sadistic evidence, that Sara had been hooded and repeatedly tied up or restrained. You could feel the lingering sense of horror in the courtroom.

In court, the prosecutor took us inside the house in Woking, Surrey, where Sara lived and where she was ultimately murdered.

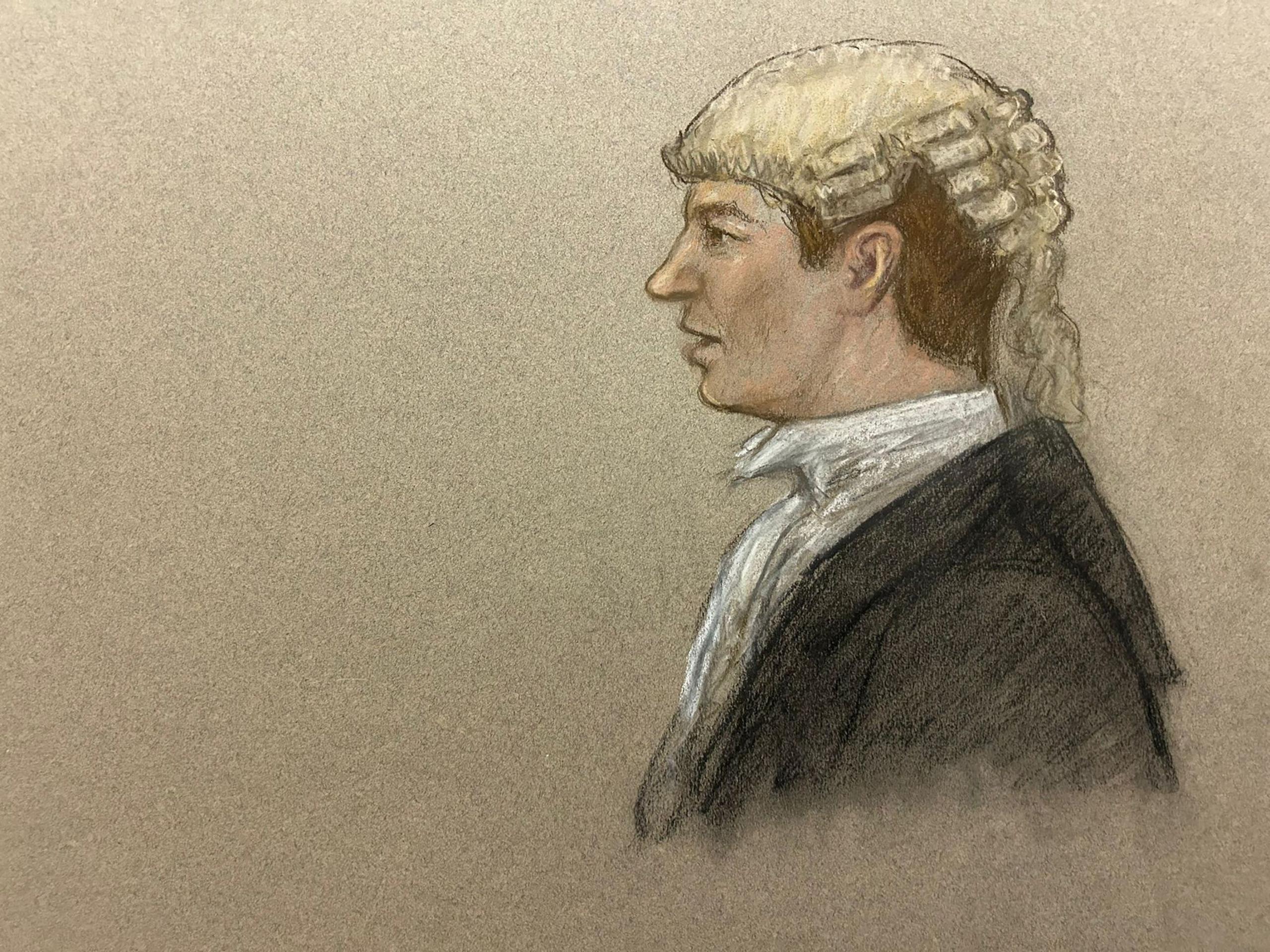

Prosecutor Bill Emlyn Jones KC described disturbing details of Sara Sharif's many injuries

We watched haunting footage from an officer’s body-worn camera of the moment police arrived to discover her body. The police officer who found Sara recalled how he had “pulled back the cover and underneath there was the body of a 10-year-old girl”.

Some witnesses gave evidence from behind a screen, shielded from the defendants and the public. One of them was Sara’s primary school teacher. It was Helen Simmons who first brought Sara's personality to life during the trial.

She described her former pupil as “often bubbly” and a girl who “at times could be sassy”. She said her “happy space” was on stage singing and performing.

There were other deeply poignant moments during the trial.

In one video we saw Sara dancing at home two days before she died. Batool cried when it was played. In another we got to hear Sara’s voice, as she played in the garden with other children one sunny day two months before she died.

Shock turned to horror

Just over three weeks into the trial Sharif’s barrister Naeem Mian KC was on his feet.

“What’s going to happen now," he said, "is Mr Sharif is going to take what amounts to the longest walk of his life from that dock to the witness box.” The courtroom fell silent.

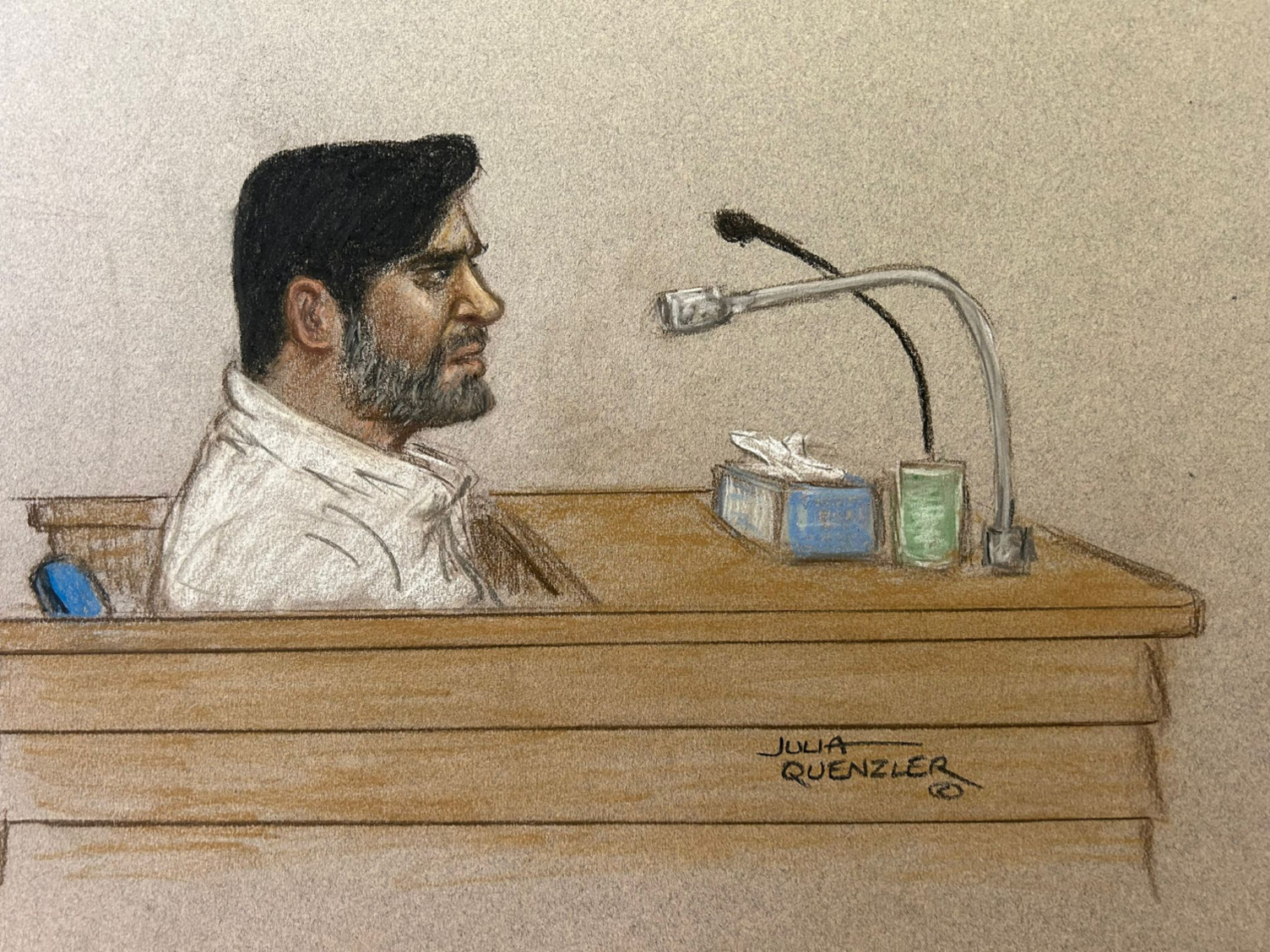

Sara’s father, slightly built and dressed in a white fleece top and jeans, appeared at the dock door and took the three steps down into the courtroom.

As he stepped up into the witness box he was already upset, pulling tissues from a box in front of him. Once he sat down his barrister slowly and carefully led him through his version of events. He spoke quietly and mumbled at times.

For the next six days Sharif maintained his daughter’s death had had nothing to do with him. He admitted slapping Sara, but denied beating her. He placed the blame firmly on his wife saying he had never been there when abuse happened. It turned out he was an exceptional liar.

During his evidence he was highly emotional and cried many times, often struggling to get his words out. “My Sara,” he would say over and over. Through tears he spoke of his “beautiful angel” whose favourite food was chicken biriyani and favourite colour was pink.

“Were you close to her?" asked his barrister. “Yes,” Sharif replied.

When his daughter died in his arms he said he had felt “numb”. “I was crushed. The whole world fallen on me.”

As he tried to convince the jury, he sounded rehearsed.

On the second day of Sharif’s evidence there was a dramatic moment. Voice raised and emotional, Sharif pointed towards his wife in the dock and called her a “psycho” and “evil”.

But it was under forensic cross-examination by his wife’s barrister that Sharif finally cracked.

Caroline Carberry KC dredged up his past, the previous partners he had allegedly threatened to kill and the arrests for false imprisonment for which he had never been charged.

“You are a lying, manipulative, controlling man,” Ms Carberry KC went on to say.

She got him to stand for her questions and took him to task when he pointed towards her client in the dock again.

Urfan Sharif at the Old Bailey

It was the seventh day of his evidence when everything changed.

Sharif was being questioned about missing the birth of one of his children. He started trying to interrupt her, while she persisted in trying to get him to answer the questions.

Eventually he managed to get it out. “I want to say something.”

“I admit what I said in my phone call and my written note, every single word.”

There was a pause as everyone took in what he had just said.

Then Ms Carberry KC ran with it, grabbing a copy of the note that he had left by his daughter’s body. She started to go through it line by line.

“Did you kill your daughter by beating?" “Yes,” he replied. “She died because of me.”

“It was you who inflicted those injuries on her wasn’t it?” “Yes,” he said.

“Do you accept causing the fractures?” “Yes ma’am.” “Did you use the cricket bat?” “Yes ma’am.” “Did you use the white metal pole?” “Yes ma’am.”

Surprise turned to shock and shock turned to horror, as he agreed to more and more cruel acts. Some jurors sat open-mouthed.

“I take full responsibility for everything,” he said.

He was shaking and crying. Batool was sobbing in the dock.

Even Sharif’s barrister was taken by complete surprise. “I had absolutely no idea he was going to do that. You can imagine my reaction when it did happen?” he would later tell the jury.

Eventually Batool ran out of court sobbing and the hearing was suspended. Some jurors were later seen in tears.

Sharif continued to deny causing the burn and bite marks on Sara.

Ms Carberry KC asked Sharif if he wanted to have the charge of murder put to him again.

“Yes ma’am,” he said, before his barrister intervened and asked to speak to him.

When the court reconvened Sharif said he did not accept he was guilty of murder. “I didn’t intend to kill her,” he said.

'How low will you stoop?'

Sharif spent nine days in the witness box. We will never know what made him crack in the end. The pressure of having to keep up with his extensive lies? Or the realisation that there was no way out?

The jury never got to hear from Sara's stepmother. Batool declined to give evidence. So we never heard her explain why she refused to provide dental impressions for comparisons to the bite marks found on Sara. Sharif and Malik had both been ruled out as a match.

We will also never know who caused the iron burn to Sara's bottom. Sharif insisted it was not him.

One day the prosecutor suggested it would have taken two people to hold Sara down and burn her. "Who was it?" he asked.

"I don't know Sir, must have been kids?" Sharif replied. "How low will you stoop?" replied the prosecutor.

What we do know is that Batool knew for at least two years that her husband was beating Sara.

After deliberating for nine hours and 46 minutes, the jury decided Sharif was not alone in murdering the ten-year-old. Batool had either assaulted Sara, or encouraged or assisted Sharif in carrying out at least some of the brutal attacks. And those had either caused or contributed significantly to her death.

In the end, Batool was the primary child carer in the house.

Sara's father Urfan Sharif and stepmother Beinash Batool were found guilty of murder

Faisal Malik, Sara's uncle, also declined to give evidence in the trial.

The jury will have been sure that he must have known what was going on in the house and did not take reasonable steps to prevent or stop the violence that led to Sara's death.

As the court assembled to hear the verdicts the judge asked for silence and respect.

Both Sharif and Batool were found guilty of murder. Malik, cleared of Sara's murder, was found guilty of causing or allowing her death. Sharif looked straight ahead, while Batool sobbed and Malik cried, as the verdicts were delivered.

The three of them were led out of the dock and down to the cells, bringing an end to the trial.

The horror that had been felt for weeks in the courtroom quietly turned into a deep sadness for Sara - the confident, chatty and caring 10-year-old girl who had big dreams of becoming a ballet dancer.

Additional reporting by Daniel Sandford.