Euphoria and rage in Bordeaux over shock poll result

Residents of Pessac in the Bordeaux region were among those to vote in the election

- Published

“I can barely believe it.”

That was one left-wing activist’s response to the exit poll which showed the left ahead in France’s parliamentary elections.

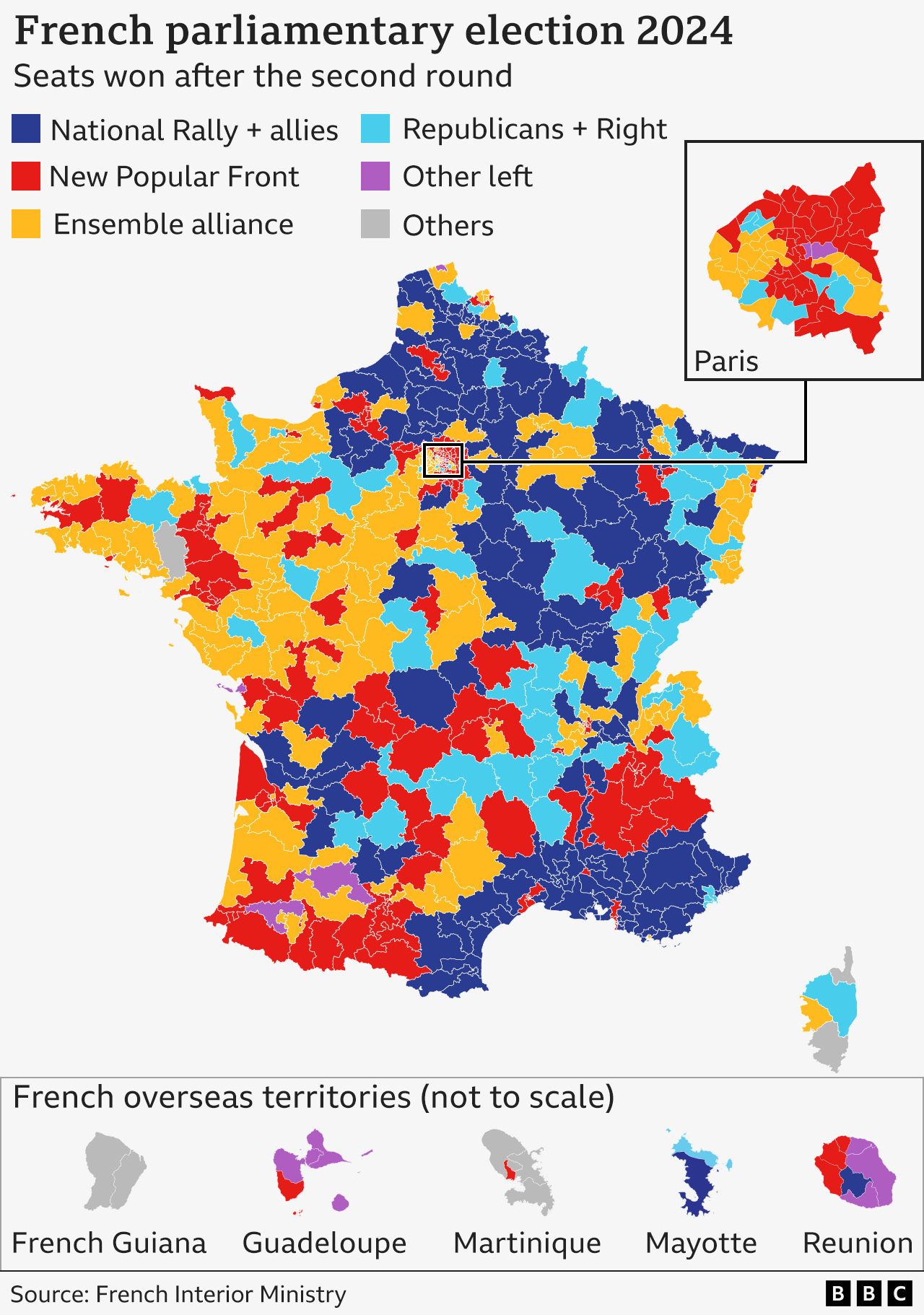

At an election count at Pessac, in the Bordeaux region, disbelief blended into euphoria as the news sunk in that the left-wing New Popular Front (NFP) - not the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) - had come first. Teary-eyed volunteers hugged each other and gave triumphant whoops as the winning NFP candidate, Sébastien Saint-Pasteur, walked in.

“I am cherishing this moment,” Salima Z, an NPF activist, told me. “I haven’t thought about what comes next yet.”

The so-called “republican front” holding was key to the NFP’s victory. The front - a type of forced tactical voting, where some candidates withdraw to leave a single option for anti-far right voters - prevented scores of RN candidates winning.

NPF activist Salima was among those celebrating the National Rally's surprise defeat

East of Bordeaux, RN candidate Sandrine Chadourne expected to easily take the seat she was standing in. But in the end, she was narrowly beaten because of voters like winemaker Paul Carrille, who said he viewed voting against the far right as his democratic duty.

“Our institutions are strong. But it would still be very bad for the far right to win,” Mr Carrille told me outside the medieval town hall in Libourne.

Voters seemed to realise that they were in a unique - for many, uniquely dangerous - political moment. Turnout in the country was the highest for 25 years. In some seats where the RN stood a chance of winning, numbers were up in the second round compared to the first.

NFP candidates were also helped by campaigns often grounded in their local areas. As Mr Saint-Pasteur, a longstanding local official, went around the town of Pessac on election day, he seemed to know many voters he greeted by name.

By contrast, his RN opponent was an 18-year-old high school student who was accused of ducking scrutiny by refusing to debate between the two rounds of voting.

But even though the RN underperformed expectations, its result was still the best in its history. It has only slightly fewer MPs than the other two blocs in parliament.

And the rage felt by its voters towards establishment politics is unlikely to dissipate. Sylvie, a first-time RN voter, told me she was angry at high taxes being used to “pay for illegal immigrants”.

“We have tried all the other parties – why not them?”

Addressing that anger before the next presidential election, due in 2027, will be the paramount task of the next government.

Mr Saint-Pasteur alluded to the scale of the challenge following his election victory.

“The French people have sent a clear signal that they do not want the RN,” he told me.

“But if, by 2027, people have not been given the answers they need, more social justice and less inequality… maybe this time Marine Le Pen will win.”