Elon Musk's Starship rocket to make second flight

Elon Musk says more than a thousand modifications have been made to the system

At a glance

Elon Musk will have another go at launching his new rocket, Starship

Its maiden flight ended when it exploded four minutes after lift-off

Engineers have since made "more than a thousand" modifications

The launch window in Texas opens at 07:00 local time (13:00 GMT)

- Published

American entrepreneur Elon Musk will have another go shortly at launching his mammoth new rocket, Starship.

The vehicle's maiden flight in April ended in spectacular style when it lost control and exploded four minutes after leaving the ground in Texas.

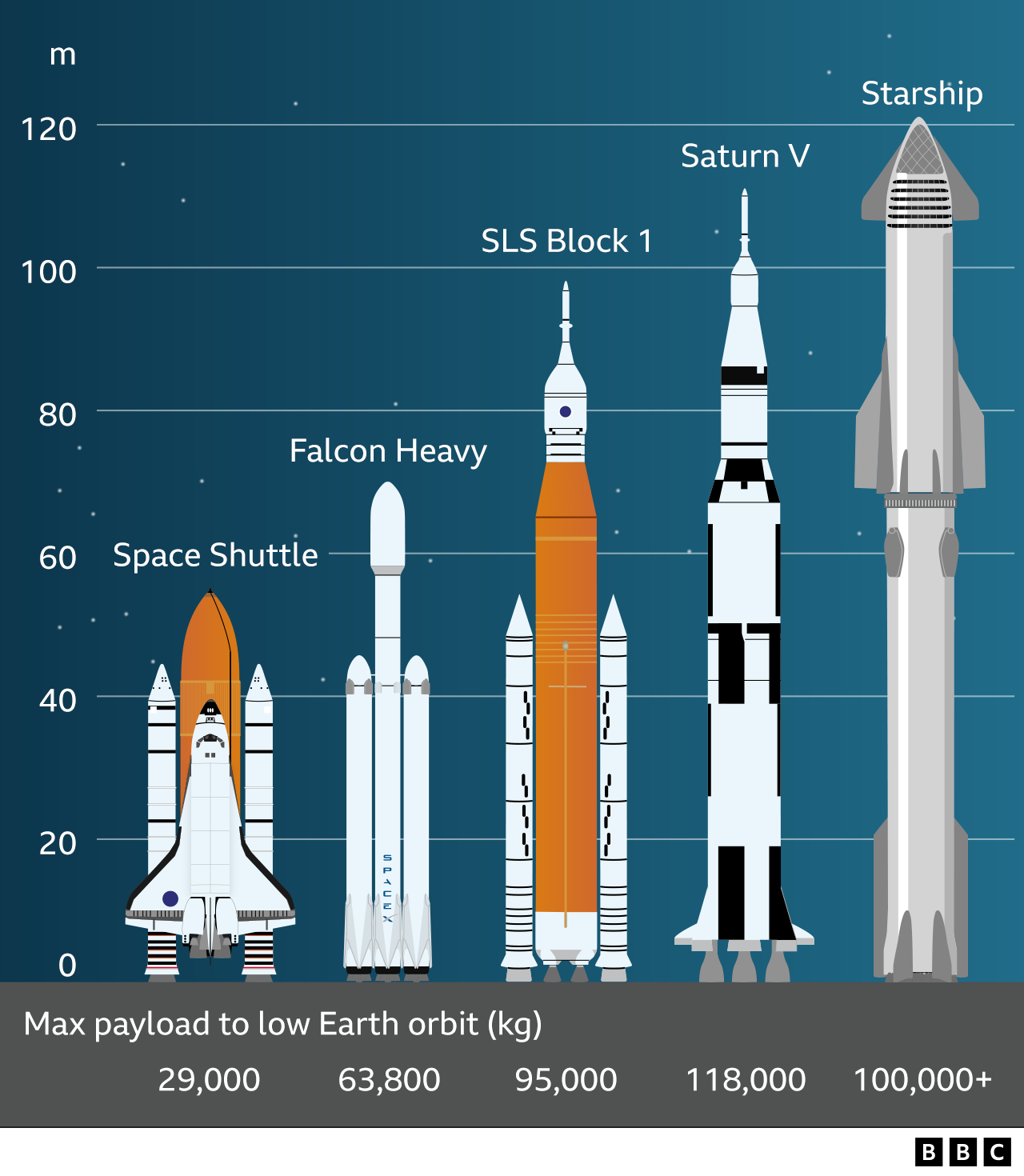

Debris from the 120m-tall (393ft) rocket fell into the Gulf of Mexico.

Engineers at Mr Musk's SpaceX company have since made "more than a thousand" changes to Starship's systems to try to make the vehicle more reliable.

Lift-off from the coastal town of Boca Chica is scheduled to occur within a 20-minute window, starting at 07:00 local time (13:00 GMT).

The planned mission profile will be broadly the same as before: to send the top part of the two-stage vehicle - the Ship - nearly one full revolution of the Earth.

The aim is for the uncrewed craft to make an ocean splashdown near Kauai, one of the islands in the Hawaiian archipelago.

If Mr Musk can get Starship working as designed, it will be revolutionary.

A fully reusable rocket capable of putting more than a hundred tonnes in orbit in one go would radically lower the cost of space activity. It would also assist the entrepreneur in his efforts to realise the long-held dream of taking people and supplies to Mars to establish a human settlement.

Musk's influence grows as world leaders flock to him

- Published20 September 2023

Elon Musk promises second Starship launch in months

- Published20 April 2023

The mantra Elon Musk follows is “test early, break it, and learn”, and engineers at his SpaceX company certainly had a lot of lessons to learn after the first flight test in April.

Starship’s fiery exhaust dug out an enormous hole under the launch pad, hurling debris in all directions. Scientists later calculated the forces generated by the vehicle's first-stage engines were similar to those found in an erupting volcano.

"The rocket exhaust went through cracks in the launchpad's concrete. It was super hot, it was approximately 2,000C, and it vaporised the groundwater," explained Dr Phil Metzger from the University of Central Florida.

"We actually used the equations of volcanoes to predict how fast ejecta would fly - 90 meters per second," he told BBC News.

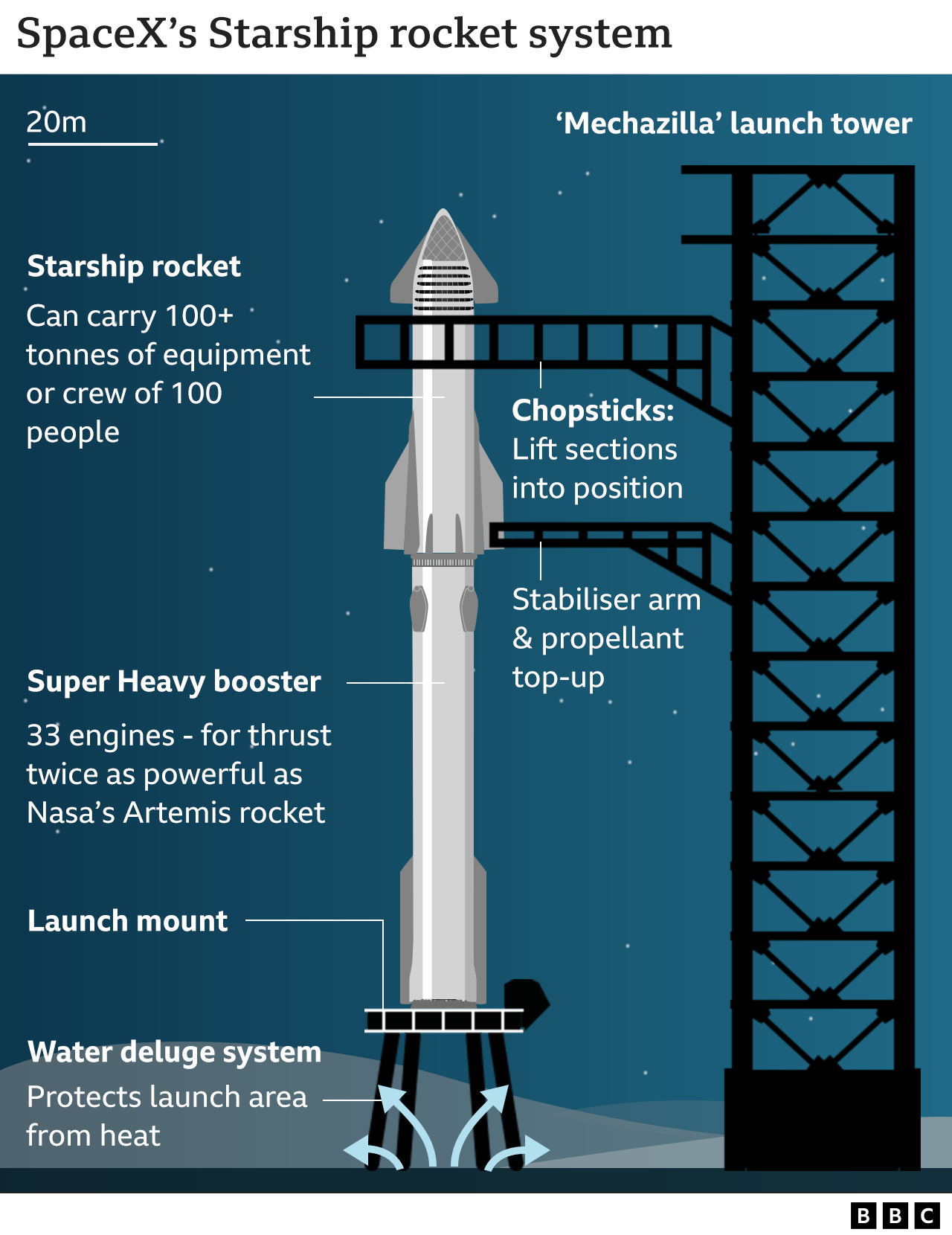

Engineers have since installed a steel plate-structure at the pad they liken to an upside-down showerhead. This will produce immense fountains of water in a bid to dampen the heat and noise at lift-off.

The debut flight ended when the vehicle broke up high above the Gulf of Mexico

SpaceX has also been working these past months to improve the performance of Starship's methane-burning Raptor engines.

There are 33 of these on the lower-stage, or Super Heavy booster as it's known, and several were seen to stop operating as the vehicle climbed higher into the sky. It's possible a few were damaged by all the flying debris at the moment of launch.

The two halves of Starship are supposed to separate a couple of minutes into a mission, once the Super Heavy booster has completed its main task of getting all the hardware airborne. In April, this detachment event never happened; and the automated command to destroy the floundering vehicle with explosive charges failed to have the desired effect.

The rocket eventually tore itself apart after tumbling end over end.

A new approach is being taken to stage separation on this next flight.

The Ship segment will fire up its engines just before separation to push itself clear. A slotted ring has been added to the area around its engines to prevent their hot exhaust gases from burning through the top of the booster.

Commentators think getting beyond staging will be the minimum requirement for SpaceX to claim progress with their innovative vehicle.

"I think you have to step beyond that this time," observed Malcolm Macdonald, professor of space technology at the University of Strathclyde, UK.

"You have to go from the point where you get all of the engines lit, you get to altitude with that capability, you get the separation, and then you progress from there to perhaps failure further in the timeline."

There was a cascade of engine failures during the April ascent

Assuming everything goes as planned, Starship will rise up and head down range across the Gulf in the direction of the Atlantic and Africa.

Stage separation is timed to occur at about two minutes and 40 seconds into the flight.

At that point, the booster's engines will shut down and the Ship with its own engines will thrust onwards for a further five minutes and 53 seconds.

SpaceX wants the Super Heavy booster to try to fly back to near the Texan coast and come down vertically, to hover just above the Gulf's waters. It will then be allowed to topple over and sink.

The Ship is expected to re-enter the Earth's atmosphere once it gets over the Pacific. It's been given protective tiling to cope with the immense heating it will experience during the descent.

A completed mission will see the Ship bellyflop into the ocean roughly 90 minutes after lift-off.

A water deluge system has been added to the launch pad

If the Ship doesn't make it all the way to waters off Hawaii and maybe even disintegrates mid-flight again, there shouldn't be a rush to judgement, says Garrett Reisman, a professor of astronautical engineering at the University of Southern California.

"I think the benefit of this rapid development approach is even though things don't look good at first, when things are blowing up - you learn so much and so quickly that you actually do converge on the correct solution much faster than if you try to get something 100% perfect the first time," he told BBC News.

"SpaceX does seem to get there in the end."