A million-dollar challenge to crack the script of early Indians

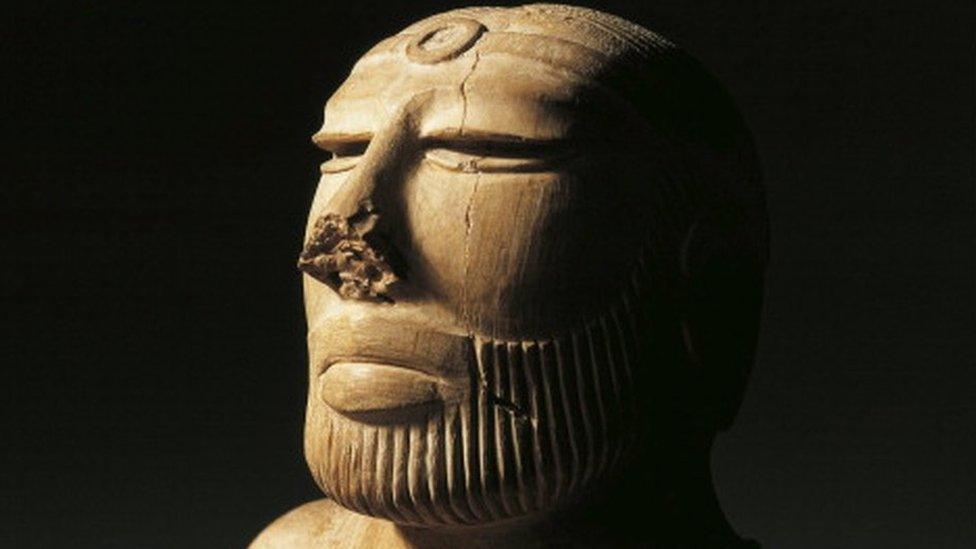

The Indus script consists of signs and symbols, primarily found on stone seals like this one

- Published

Every week, Rajesh PN Rao, a computer scientist, gets emails from people claiming they've cracked an ancient script that has stumped scholars for generations.

These self-proclaimed codebreakers - ranging from engineers and IT workers to retirees and tax officers - are mostly from India or of Indian origin living abroad. All of them are convinced they've deciphered the script of the Indus Valley Civilisation, a blend of signs and symbols.

"They claim they've solved it and that the 'case is closed'," says Mr Rao, Hwang Endowed Professor at the University of Washington and author of peer-reviewed studies on the Indus script.

Adding fuel to the race, MK Stalin, the chief minister of southern India's Tamil Nadu state, recently upped the stakes, announcing a $1m prize for anyone who can crack the code.

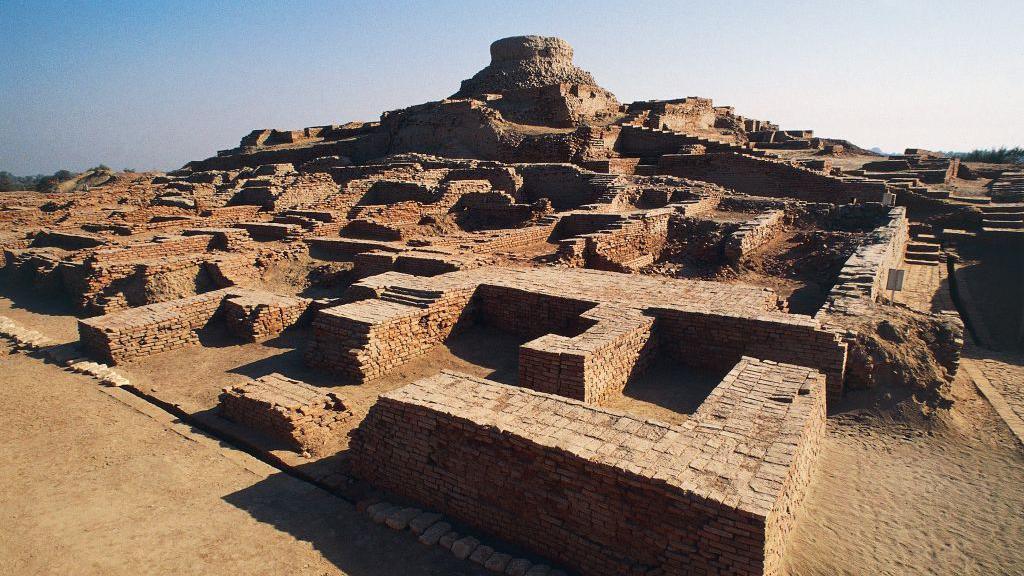

The Indus, or Harappan, civilisation - one of the world's earliest urban societies - emerged 5,300 years ago in present-day northwest India and Pakistan. Its austere farmers and traders, living in walled, baked-brick cities, thrived for centuries. Since its discovery a century ago, around 2,000 sites have been uncovered across the region.

The reasons behind the society's sudden decline remain unclear, with no apparent evidence of war, famine or a natural disaster. But its greatest mystery is its undeciphered script, leaving its language, governance and beliefs shrouded in secrecy.

The ruins of an Indus valley site in Pakistan - it was one of the world's earliest urban societies

For over a century, experts - linguists, scientists and archaeologists - have tried to crack the Indus script. Theories have linked it to early Brahmi scripts, external, Dravidian and Indo-Aryan languages, Sumerian, and even claimed it's just made up of political or religious symbols.

Yet, its secrets remain locked away. "The Indus script is perhaps the most important system of writing that is undeciphered," says Asko Parpola, a leading Indologist.

These days, the more popular spectacular theories equate the script with content from Hindu scriptures and attribute spiritual and magical meanings to the inscriptions.

Most of these attempts ignore that the script, made up of signs and symbols, mostly appears on stone seals used for trade and commerce, making it unlikely they contain religious or mythological content, according to Mr Rao.

There are many challenges to deciphering the Indus script.

First, the relatively small number of scripts - about 4,000 of them, almost all on small objects such as seals, pottery and tablets.

Then there's the brevity of each script - average length of about five signs or symbols - with no long texts on walls, tablets or upright stone slabs.

Consider the commonly found square seals: lines of signs run along their top, with a central animal motif - often a unicorn - and an object beside it, whose meaning remains unknown.

Many seals feature a unicorn motif, with an unidentified object beside it

There's also no bilingual artefact like the Rosetta Stone, which helped scholars decode Egyptian hieroglyphs. Such artefacts contain text in two languages, offering a direct comparison between a known and unknown script.

Recent advancements in deciphering the Indus script have used computer science to tackle this ancient enigma. Researchers have used machine learning techniques to analyse the script, trying to identify patterns and structures that could lead to its understanding.

Nisha Yadav, a researcher at the Mumbai-based Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), is one of them. In collaboration with scientists like Mr Rao, her work has focused on applying statistical and computational methods to analyse the undeciphered script.

Using a digitised data set of Indus signs from the script, they have found interesting patterns. A caveat: "We still don't know whether the signs are complete words, or part of words or part of sentences," says Ms Yadav.

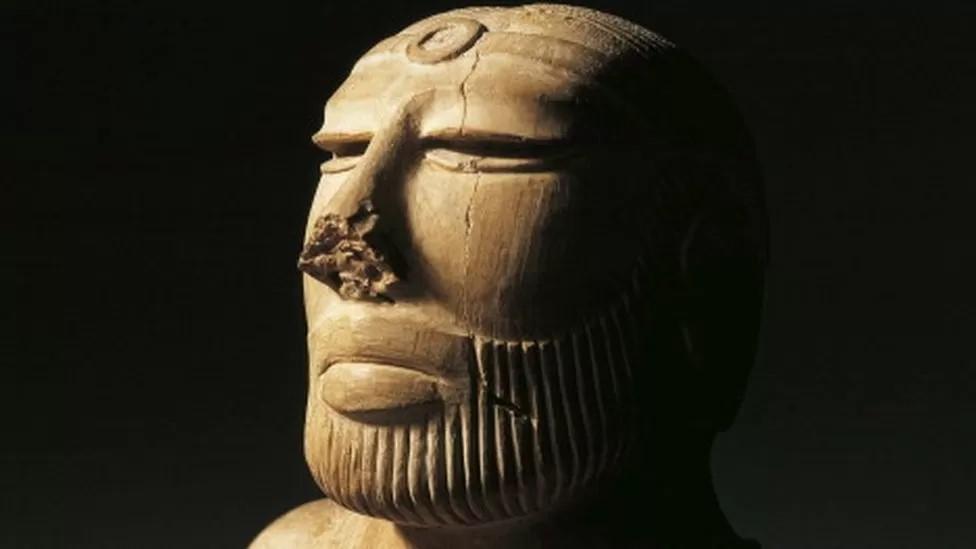

A sculpture, possibly of a priest, discovered from an ancient Indus ruin, now in Pakistan

Ms Yadav and co-researchers found 67 signs that account for 80% of the writing on the script. A sign which looks like a jar with two handles turned out to be the most frequently used sign. Also, the scripts began with a large number of signs and ended with fewer of them. Some sign patterns appear more often than expected.

Also, a machine-learning model of the script was created to restore the illegible and damaged texts, paving the way for further research.

"Our understanding is that the script is structured and there is an underlying logic in the writing," says Ms Yadav.

To be sure, several ancient scripts remain undeciphered, facing challenges similar to the Indus script.

Mr Rao cites scripts like Proto-Elamite (Iran), Linear A, external (Crete), and Etruscan (Italy), whose underlying language is unknown.

Others, like Rongorongo (Easter Island) and Zapotec (Mexico), have known languages, "but their symbols remain unclear". The Phaistos Disc from Crete - a mysterious, fired clay disc from the Minoan civilisation - "closely mirrors the Indus script's challenges - its language is unknown, and only one known example exists".

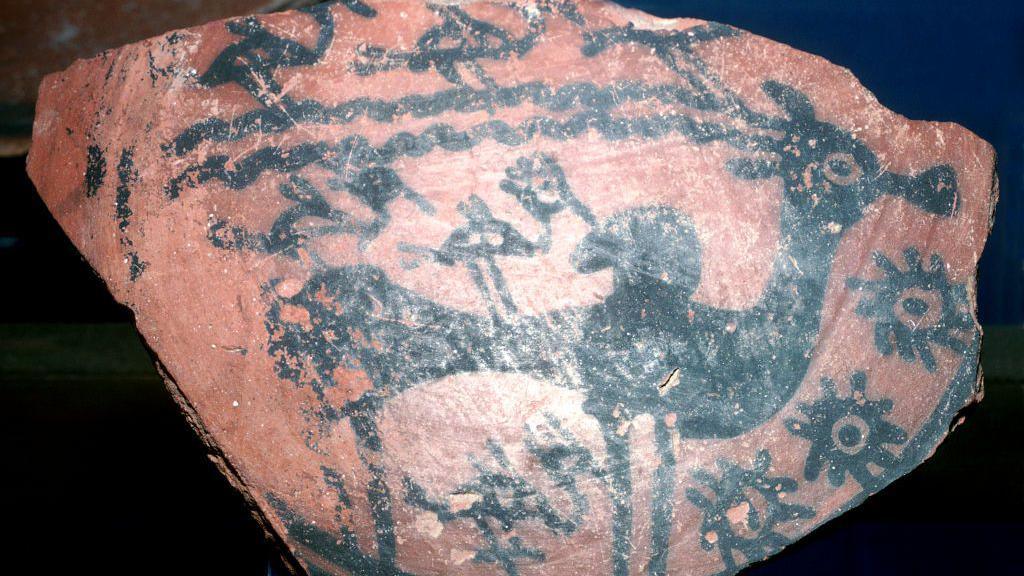

Pottery with humped bulls and birds recovered from an Indus site

Back in India, it is not entirely clear why Mr Stalin of Tamil Nadu announced a reward for deciphering the script. His announcement followed a new study linking Indus Valley signs to graffiti found in his state.

K Rajan and R Sivananthan analysed over 14,000 graffiti-bearing pottery fragments from 140 excavated sites in Tamil Nadu, which included more than 2,000 signs. Many of these signs closely resemble those in the Indus script, with 60% of the signs matching, and over 90% of south Indian graffiti marks having "parallels" with those from the Indus civilisation, the researchers claim.

This "suggests a kind of cultural contact" between the Indus Valley and south India, Mr Rajan and Mr Sivananthan say.

Many believe Mr Stalin's move to announce an award positions him as a staunch champion of Tamil heritage and culture, countering Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which rules in Delhi.

But researchers are confident that there will be no claimants for Mr Stalin's prize soon. Scholars have compiled complete, updated databases of all known inscribed artefacts - crucial for decipherment. "But what did the Indus people write? I wish we knew," says Ms Yadav.

- Published5 October 2023

- Published30 December 2018