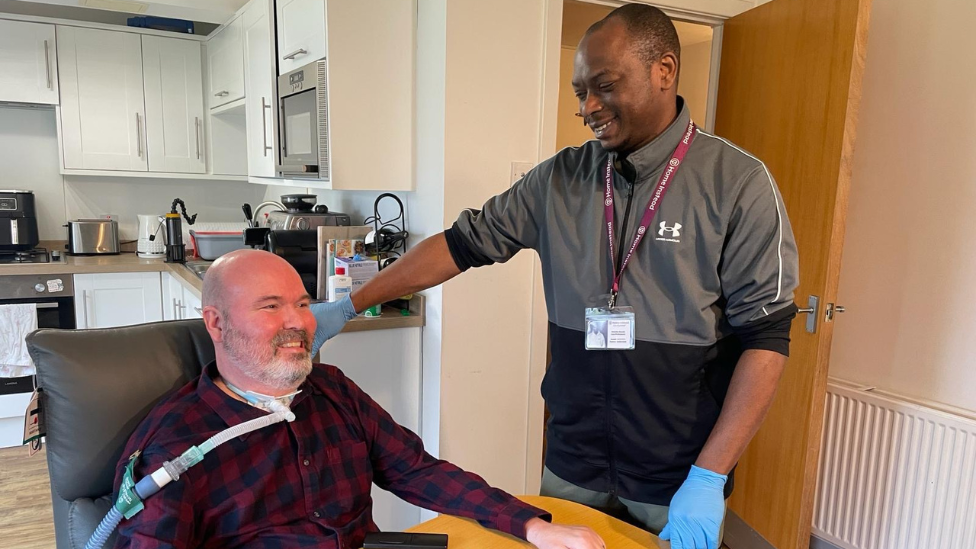

MND patient: 'Without my carers I would not be here'

Brian Murphy says the care service will suffer under the new rules

- Published

A former cardiologist who lives with motor neurone disease (MND) said he "would not be here" without his team of carers.

Brian Murphy requires round-the-clock support from workers including Afe Akande, who came to the UK almost three years ago from Nigeria.

But tougher visa restrictions mean those moving from overseas will no longer be allowed to bring their families to Scotland.

Afe brought his three children so his wife, Temi, could study for her masters degree.

But if he was applying to come to the UK now, Afe would be living thousands of miles from home without Ethan, 10, Elsa, eight, and two-year-old Ean.

Experts said the decision would increase demands on a sector already struggling for staff.

More than 2,000 overseas health and care worker visas were issued in Scotland last year, figures show.

The UK government claims the new rules will help to halt abuse of the system.

However Brian, 50, who underwent a tracheotomy and had a breathing tube inserted in his windpipe last year, described the policy as "unbelievable".

Brian and Afe have become close friends

Including Afe, his seven-strong team includes carers from Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Romania.

Without them, he said he would never have been released back to his own home from hospital.

"We have managed to have a team of highly-skilled carers and they can’t just be replaced," Brian said.

"Every one of them are wonderful people and they are part of our family now.

"Without them, I would either never have got out of ICU or I would be in a care home. I can’t contemplate either of those options."

Brian added: "I genuinely don’t think I would be here."

Afe said having his family close helped him cope with the demands of the job

Afe began working in the care sector in 2021 after his wife picked up part-time social care work while studying at university.

He was assigned to Brian’s Glasgow home last year through care provider Home Instead and the pair struck up a close bond.

Brian refers to him as "McAfe" while Afe and his colleagues have taught Brian a few words of Pidgin.

They spent Christmas Day together at Brian and wife Gillian’s home with some of the other carers and their families.

They are settled now in the city, but Afe believes the new rules will only stop those in similar positions from bringing their skills to the country.

"For a carer not to have his family with them, it is emotionally stressful,” he said.

"If my wife calls me and tells me one of our children is ill, I am able to go after work and see what is going on.

"But if they were back in Nigeria, I can’t concentrate working with Brian. I would be confused, I would be distracted."

He added that having his family close by provided the physical, emotional and mental support needed to "fully concentrate on taking care of the client".

Afe said: "You get to go home and see your kids, they smile at you, your wife kisses you, it’s lovely.

"And it gives you that motivation to go out the next day.”

Brian and wife Gillian hosted some of Brian's care team for Christmas dinner

Others in Brian’s team have not been as fortunate.

Another care worker, from Zimbabwe, has been separated from his family for about 18 months due to UK Home Office red tape.

Figures released to the BBC under Freedom of Information laws show that 4,406 care worker visas were issued to sponsoring organisations in Scotland between March 2021 and September last year.

A total of 33 overseas care worker visas were issued in 2020/21 but this jumped to 1,893 in 2022/23.

And between April and September last year a total 1,678 visas were issued.

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh said the new policy was “regressive” and seriously threatened recruitment in adult social care.

Its president, Prof Andrew Elder, said: “The new immigration polices from the Home Office may hinder, not help, care homes struggling to fill vacancies and it is members of the public – both those who receive care and those who provide it - who could suffer the most”.

As of September last year about 101,000 Health and Care Worker Visas were granted, with around 120,000 Dependant Visas going to family members.

Home Secretary James Cleverly said the legislation had been introduced in a bid to curb what he called “clear abuse and manipulation” of the immigration system.

The changes, announced in December, included hiking the minimum salary needed for skilled overseas workers from £26,200 to £38,700.

The minimum income for family visas has also risen to £38,700.

He said the legislation had been introduced to “protect and prevent the continued undercutting” of British workers.

But for those who rely on care, like Brian, it is a worrying time.

“The care sector is so reliant on overseas workers and we will lose them because no-one will want to come over without their family," he said.

“The UK government seems to think there is a pool of British workers waiting to take these jobs, but we have seen no sign of that.

“If we lose those numbers, I don’t know what kind of state we will be in.”