How should countries deal with falling birth rates?

Birth rates are falling in two thirds of the world

- Published

The first thing you need to know about the so-called demographic timebomb facing countries such as the UK and US is to never call it that.

With birth rates continuing to decline in both nations, it is tempting to use the timebomb term. However, it is greatly disliked by demographers, the experts that study population change.

“Number one, I hate the phrase,” says Sarah Harper, professor of gerontology (the study of the impact of aging) at the University of Oxford.

“I do not think there is a demographic timebomb, it is part of the demographic transition. We knew this was going to happen, and happen across the 21st Century. So, it is not unexpected, and we should have been preparing for this for some time.”

However, the scale of the future problem is immense. For a country in the developed world to increase or maintain its population it needs a birth rate of 2.1 children per woman on average. This is known as the “replacement rate”.

Prof Sarah Harper says that increased immigration can solve the problem of lower birth rates

Yet the latest figures for England and Wales show that the average birth rate, also called the total fertility rate, declined to 1.49 children per woman, external in 2022, from 1.55 in 2021. The rate has been falling since 2010.

It is a similar picture in Scotland and Northern Ireland, which record their data separately.

Meanwhile, in the US the fertility rate fell last year to 1.62, a record low., external Back in 1960 it was 3.65.

“In fact, two thirds of the world’s countries now have childbirth rates below the replacement rate,” adds Prof Harper. “Japan is low, China is low, South Korea is the lowest in the world.”

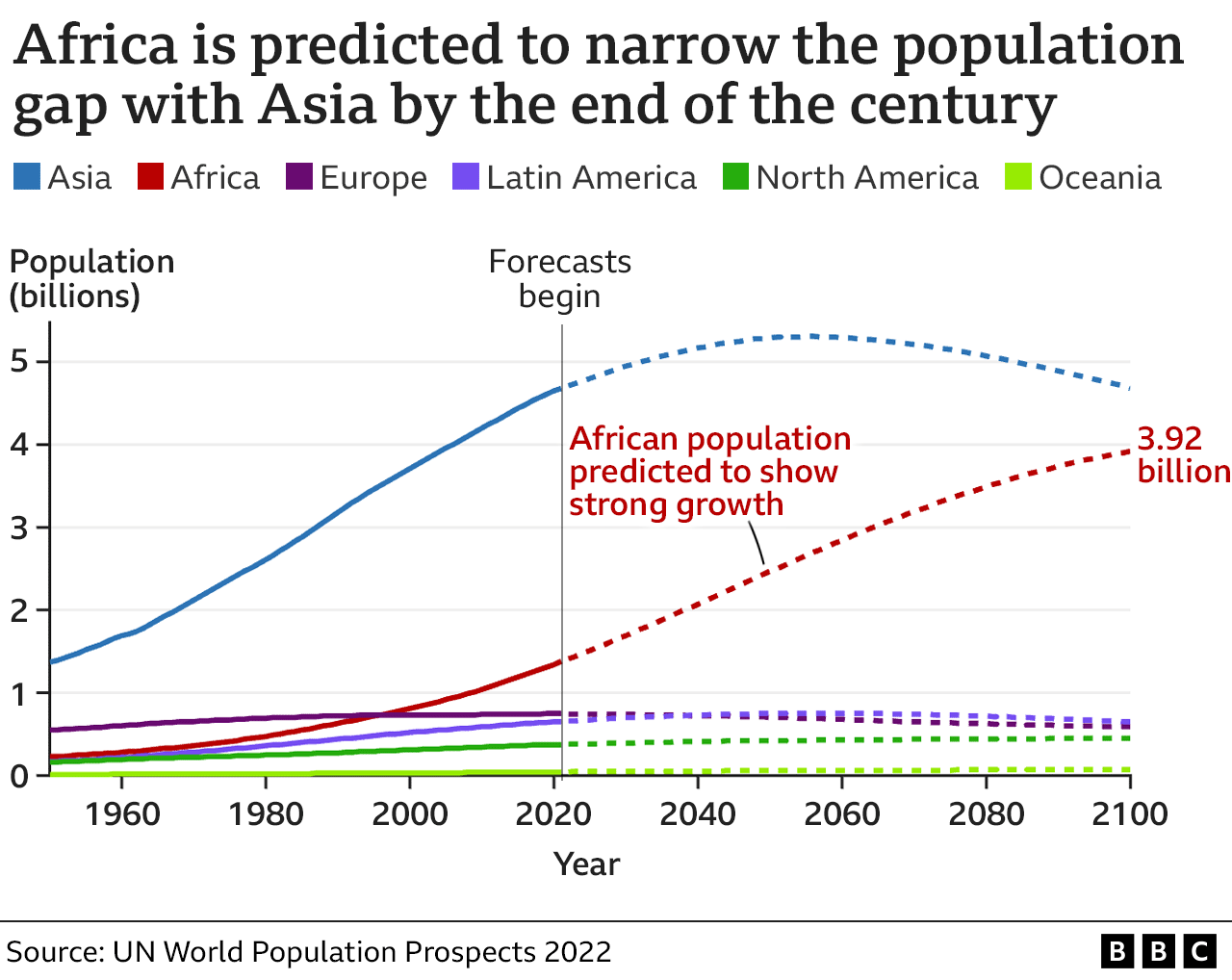

Population growth is really only limited to sub-Saharan Africa these days.

But why the concern about falling birth rates? The economic problems they can cause are significant, as countries face the impact of both aging and declining populations, and a smaller workforce in relation to the number of pensioners.

For example – where will a nation’s economic growth come from if companies cannot recruit enough workers? And how can a smaller workforce afford to pay for the pensions of a much larger retired population? Those are questions that make government economists wince.

To try to increase birth rates, countries can make it easier for women to have children, by providing more generous childcare provision, such as tax breaks and extended, fully-paid maternity leave. In addition, companies could be compelled to offer new mums and dads more flexible working hours, and provide workplace creches.

However, while such policies might slow the decline, they rarely reverse it.

Put simply, the more women are educated, the more they work and save, the better their lives are.

Many women would instead prefer not to take the hit to their earnings and career prospects that becoming a mother often causes.

So they have fewer children, or none at all.

There are basically two main ways in which a country can deal with a falling birth rate – you can keep your population heathier and employed for longer, or you can have large-scale immigration.

Singapore is one of the fastest-ageing countries in the world, and it is going for the first option.

“There is a lot of effort being put into raising the retirement age, training in middle life, and encouraging companies - which have to offer you re-employment up to the age of 69 - to hire older workers,” says Prof Angelique Chan. She is the inaugural executive director of Singapore’s Centre for Ageing Research & Education.

By re-employment, Prof Chan means older workers being able to stay in work after they have reached retirement age, if they so wish.

Currently the retirement age in Singapore is 63, but this is due to rise to 64 in 2026, , externaland to 65 by 2030. By that year the age to which people in re-employment can stay in work is expected to have risen to 70.

The Singapore government wants more older Singaporeans to stay in work

Prof Chan says that the Singaporean government is also increasing efforts to ensure that every citizen has a doctor “who must take care of you and monitor your condition, and make sure we have heathier cohorts who can continue to work”.

She adds that Singapore is spending a huge amount of money “so we have the healthiest kind of population, giving people the opportunity to work [in their old age]”.

In the US, Ronald Lee, emeritus professor of economics at the University of California, says that a growing number of older Americans are having to work to cover their living expenses., external

“If we look at the proportion of consumption of 65-year-olds and older in the USA that is funded by continuing to work, it is significantly higher than in other developed countries,” he says.

Prof Lee adds that this is not a bad thing. “I think it is fundamental for the whole world, to get over the idea that older people are entitled to an indefinitely long period of leisure at the end of their life.

“People are healthier, vigorous, cognitively sharper, and ready to go on at much older ages than used to be the case. I hope to see retirement ages rising well into the 70’s.”

Currently, Americans only get a full social security pension from 66 years and two months. But that will gradually rise to 67., external

Prof Lee’s thoughts may not be very popular with many people, but economically it looks inevitable. As life expectancy increases it becomes increasingly difficult to afford ever longer retirements. Something has to give, and working longer is the obvious solution.

There is, however, another answer to this problem, as Prof Harper makes clear - increased immigration. Yet this is obviously a hot political potato on both sides of the Atlantic.

“Migration could easily solve the problem of lower birth rates from a demographic point of view,” she says. “There are political and policy issues, but demographically what we should be doing is allowing those countries with huge child-bearing rates, and with huge numbers of workers for maybe the next four decades, to be able to flow across the world and make up the slack.”

We all know there are huge pressures against large-scale immigration, although even populist regimes often turn a blind eye to it when necessary.

Elizabeth Kuiper, associate director of the European Policy Centre think tank, says Hungary is a case in point. Its government claims to have a zero-tolerance attitude to migrants, but “we know that while these countries will not admit it publicly, in sectors like care and health care they have developed unspoken strategies for selective migration”.

The problem is, of course, that in most of the developed world immigration is nowhere near the level necessary to make up for an aging population, and yet it is already deeply unpopular.

The demographic experts know something has to give – countries will need to make people work longer, or increase immigration, and probably both. But to do that needs political consensus, and politicians know that asking people to approve additional immigration, and the need to work for more years in later life, is not a vote winner.