Ancient trees reveal last summer hottest in 2,000 years

Italy was one of a number of European countries to experience a prolonged heatwave last summer

- Published

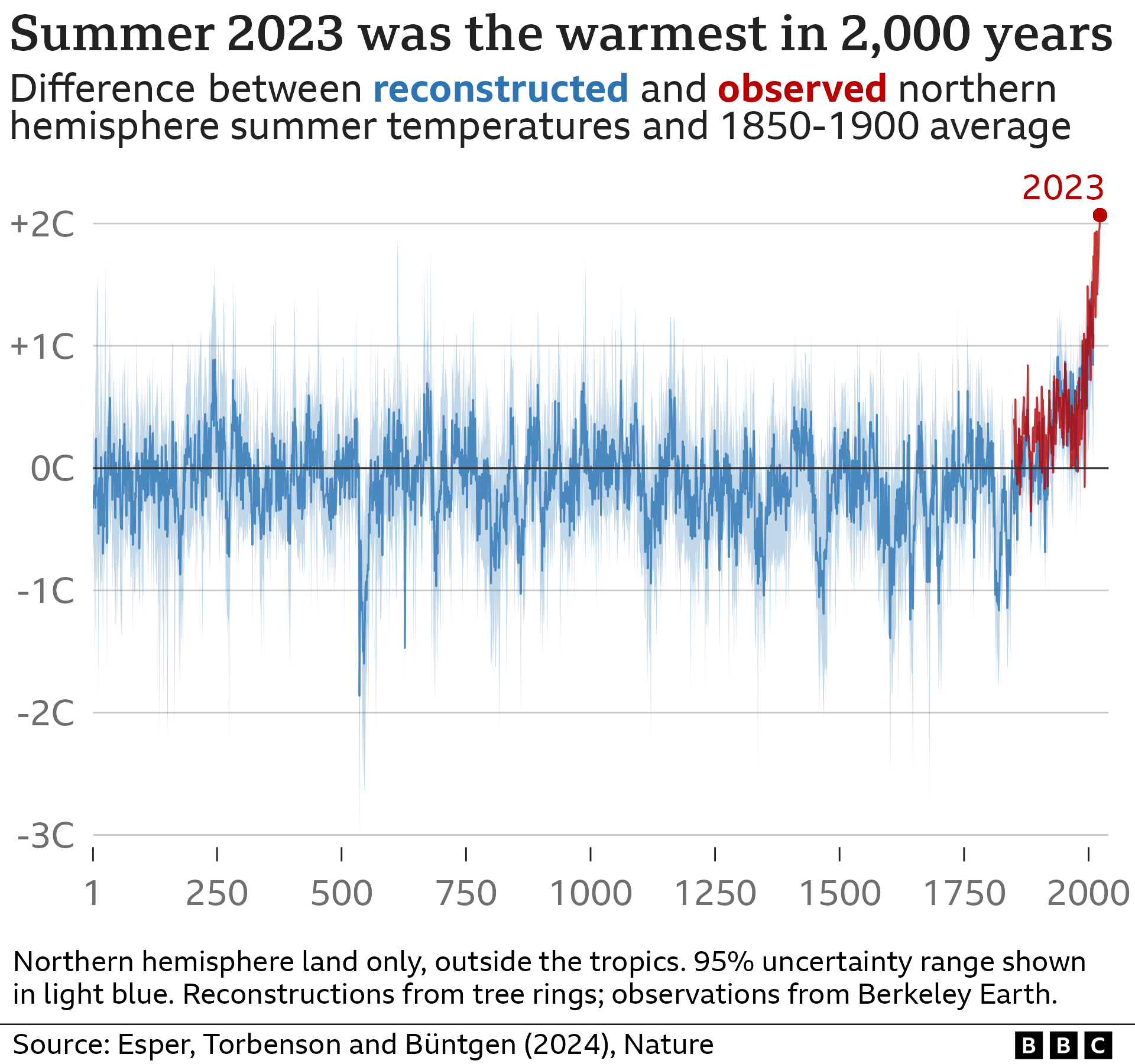

Clues hidden deep in the trunks of ancient trees have revealed that last summer was the northern hemisphere's hottest in 2,000 years.

Last year had already been confirmed as the world's warmest on record by a large margin, at least since 1850, due to climate change.

But tree rings, which record temperature information far further back than even Victorian scientific records, now show just how unprecedented last year's scorching temperatures were.

Researchers say that temperatures last June, July and August were nearly 4C warmer than the coldest summer two millennia ago.

Oceans suffer from record-breaking year of heat

- Published8 May 2024

2023 confirmed as world's hottest year on record

- Published9 January 2024

Climate scientists have repeatedly shown that global temperatures have been rising rapidly in recent decades. According to the UN's climate body, the last time the world was consistently this warm may have been more than 100,000 years ago, external.

These conclusions come from records like ice cores and deep sea sediments, which can give a good indication of the Earth's geological past, but cannot pinpoint individual years or even decades far back in time.

For this, tree rings are particularly valuable. They not only show the tree's age, but also record detailed information about the state of the climate each year as they grow.

"That is the beauty of tree ring records," Ulf Büntgen, professor of environmental systems analysis at the University of Cambridge and co-author of the study, told BBC News.

Researchers take tree ring samples using cores from thousands of alive and dead trees to build a more reliable picture of past climates

Scientists looked at living specimens as well as fossils, from the European Alps to the Russian Altai mountains. They focussed on trees living at altitude, where the impact of summer growth would be most clearly felt.

In such places rings are usually wider in warmer years, when there is more growth, and thinner in colder years.

Using the nine longest temperature-sensitive tree ring chronologies, researchers had built a picture of summer temperatures dating back two millennia for the northern part of the world, outside of the tropics.

By using such a large dataset - containing many thousands of trees in different parts of the hemisphere - the researchers can be more confident that their record represents how temperatures have changed, rather than more local disturbances like disease.

By measuring the width of each ring, scientists can gain insights into temperatures at the time that the tree grew

The authors combined the long-term tree ring record with modern temperature data.

They found that the summer of 2023 was 2.07C warmer than the "pre-industrial" period of 1850-1900.

Compared with the coldest summer in the record, year 536, last summer was 3.93C warmer.

Like many colder years, 536 was impacted by a large volcanic eruption which put more sulphur into the atmosphere, helping to cool the planet.

Volcanic activity has also been linked to cooler periods such as the Little Antique Little Ice Age in the 6th Century and the Little Ice Age, which spanned roughly from 1350 to 1850.

The warmest summer in the tree ring reconstruction before industrial times was year 246, but the researchers say that even this does not come close to the recent warmth.

Even taking account of the large uncertainties, the authors say summer 2023 surpassed this range of natural climate variability by 0.5C at the very least.

Researchers say the tree ring information is a huge addition to what we know about our changing climate over history.

Even in the 1850-1900 period, there were only 58 weather stations recording temperatures around the world, with 45 of them in Europe.

The consequence is temperatures during this period may actually have been overestimated, because of the way in which these measurements were taken.

The new study suggests this means that the world may have actually warmed around a quarter of a degree more than typically reported.

A woman covers herself from the sun with a fan, in Valencia, Spain in August last year

While the researchers say that human activities are responsible for the vast majority of the 2023 summer warmth above pre-industrial levels, they also note that temperatures have been amplified by El Niño.

This naturally occurring climate pattern sees warm waters come to the surface of the Pacific and help push up air temperatures globally.

El Niño was first noted by South American fishermen in the 17th Century but tree ring data helps to show that it dates back much further in time.

The most recent El Niño episode helped make 2023 the warmest year on record, but because it has continued into the early part of 2024, it may also make 2024 a record warm 12 months.

What is El Niño and how does it change the weather?

- Published16 April 2024

The authors say the key conclusion from their work is the need for rapid reductions in emissions of planet-warming gases.

“The longer we wait, the more expensive it will be and the more difficult it will be to mitigate or even stop that process and reverse it,” said lead author, Prof Jan Esper from Johannes Gutenberg University, in Germany.

“That is just so obvious,” he said.

“We should do as much as possible, as soon as possible.

The new study has been published, external in the journal, Nature.