'Two laptops, six plugs': The South Korean cafes grappling with students who don't leave

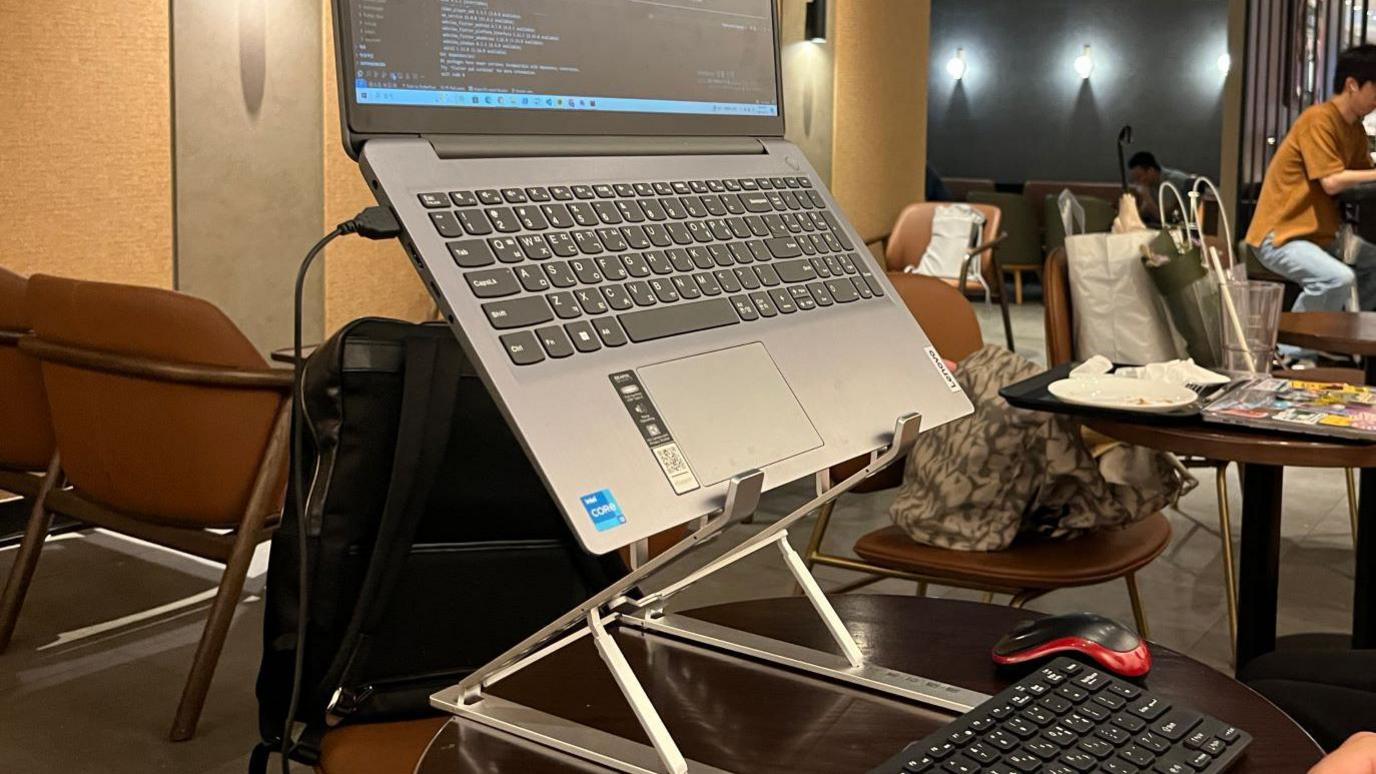

The 'desk' of a 33-year-old developer in Starbucks

- Published

In the affluent Seoul neighbourhood of Daechi, Hyun Sung-joo has a dilemma.

His coffee shop is sometimes visited by Cagongjok, a term for mostly young South Koreans who love to study or work at cafes, but there's a limit.

He says one customer recently set up a workspace in his cafe that included two laptops and a six-port power strip to charge all their devices - for an entire day.

"I ended up blocking off the power outlets," he tells the BBC.

"With Daechi's high rents, it's difficult to run a cafe if someone occupies a seat all day."

The cultural phenomenon of Cagongjok is rampant in South Korea, especially in areas with large numbers of students and office workers. They dominate cafes often on a much greater scale than other Western countries like the UK, where those studying are often surrounded by others there to socialise.

And Starbucks Korea warned this month that a minority of people are going further than just laptops, such as bringing in desktop monitors, printers, partitioning off desks or leaving tables unattended for long periods.

The chain has now launched nationwide guidelines aimed at curbing "a small number of extreme cases" where elaborate setups or prolonged empty seats disrupt other customers.

Starbucks said staff would not ask customers to leave, but rather provide "guidance" when needed. It also cited previous cases of theft when customers left belongings unattended, calling the new guidelines "a step toward a more comfortable store environment".

It doesn't seem to be deterring the more moderate Cagongjok though, for whom Starbucks has been somewhat of a haven in recent years and continues to be.

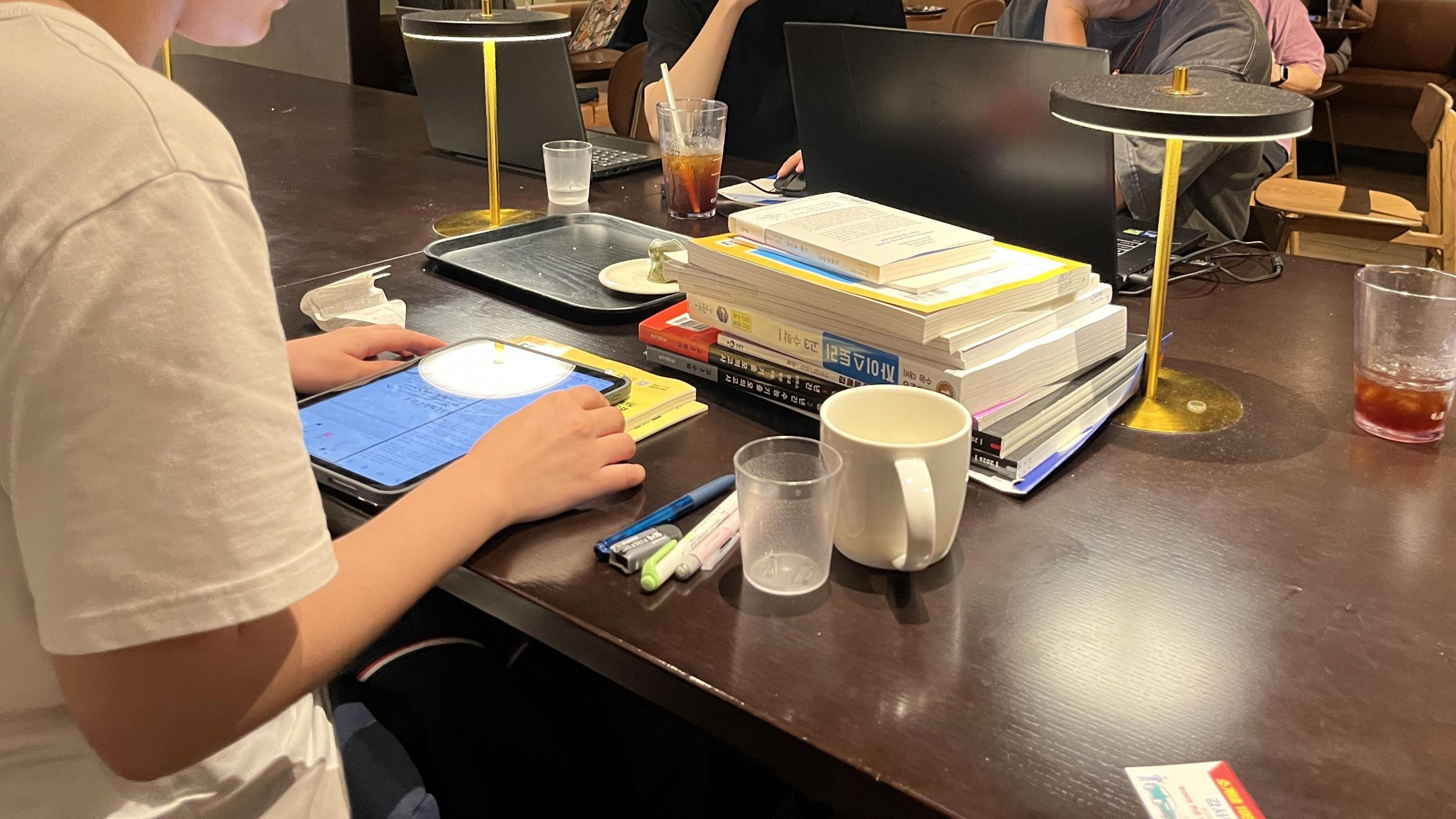

Students often set up study areas in South Korean cafes

On a Thursday evening in Seoul's Gangnam district, a Starbucks branch buzzes quietly with customers studying, heads down over laptops and books.

Among them is an 18-year-old student who dropped out of school and is preparing for the university entrance exam, "Suneung".

"I get here around 11am and stay until 10pm," she tells the BBC. "Sometimes I leave my things and go eat nearby."

We have seen no bulky equipment during our visits to Starbucks since the new guidelines were issued on 7 August, though we did see one man with a laptop stand, keyboard and mouse. Some customers still appear to be leaving their seats unattended for long periods, with laptops and books spread across tables.

When asked whether its new restrictions have led to visible changes, Starbucks Korea told the BBC it was "difficult to confirm".

Some students set up their belongings and then left a Starbucks seen here in Suwon

Reactions to Starbucks' move have been mixed. Most welcome the policy as a long-overdue step toward restoring normalcy in how cafes are used.

This is particularly so among those who visit Starbucks for relaxation or conversation, who say it has become difficult to find seats because of Cagongjok, and that the hushed atmosphere often made them feel self-conscious about talking freely.

A few have criticised it as overreach, saying the chain has abandoned its previously hands-off approach.

It reflects a wider public discussion in South Korea over Cagongjok that has been brewing ever since it started taking off in 2010, coinciding with the growth of franchised coffee chains in the country. That has kept growing, with the country seeing a 48% increase in coffee shops over the past five years, according to the National Tax Service, nearing 100,000.

Some 70% of people in a recent survey of more than 2,000 Gen Z job seekers in South Korea by recruitment platform Jinhaksa Catch said they studied in cafes at least once a week.

'Two people would take up enough space for 10 customers'

Dealing with "seat hogging" and related issues is a tricky balance, and the independent cafes grappling with a similar thing have deployed a range of approaches.

While Hyun has experienced customers bringing multiple electronic devices and setting up workstations, he says extreme cases like this are rare.

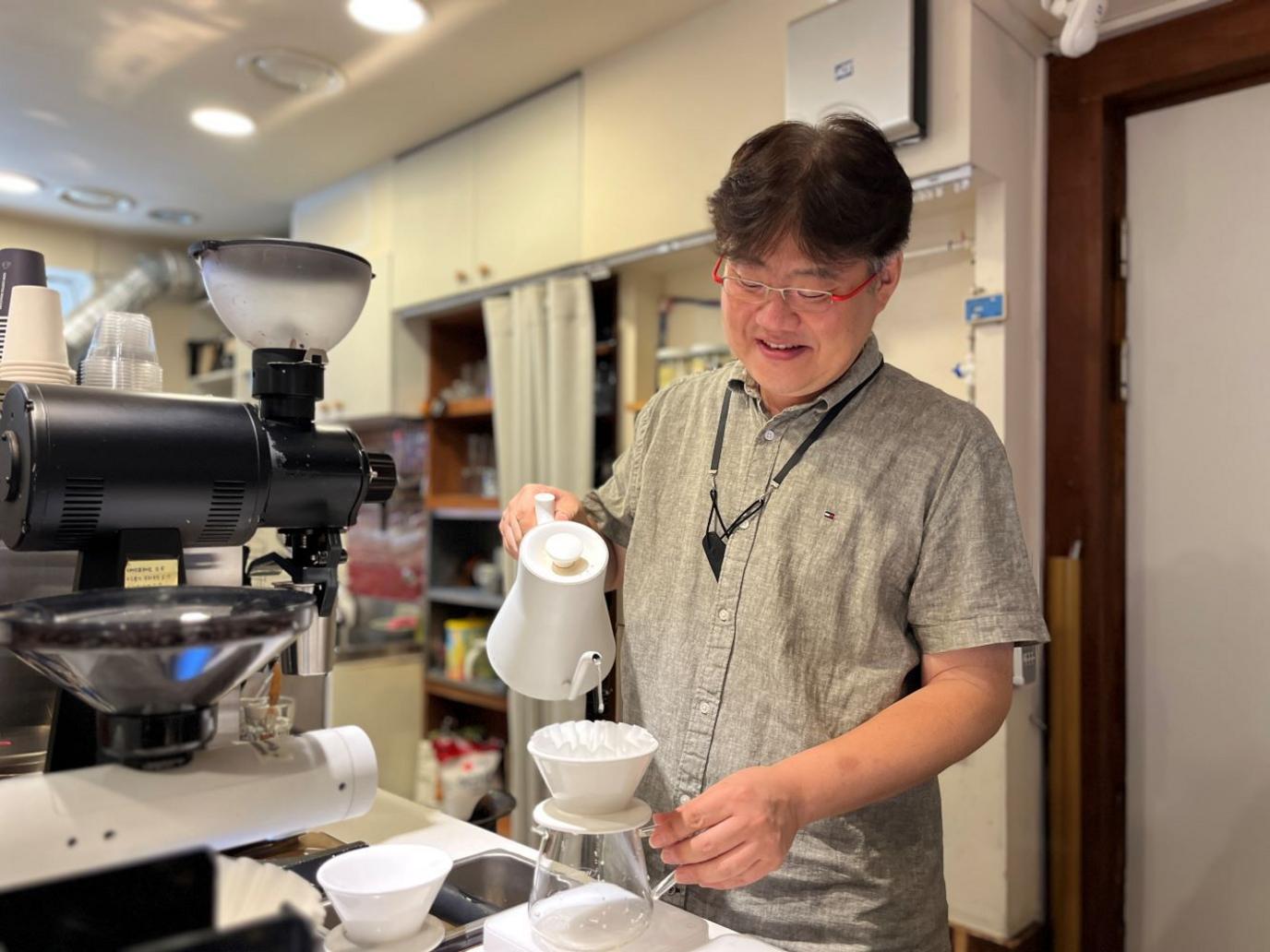

"It's maybe two or three people out of a hundred," the cafe owner of 15 years says. "Most people are considerate. Some even order another drink if they stay long, and I'm totally fine with that."

Hyun's cafe, which locals also use as a space for conversation or private tutoring, still welcomes Cagongjok as long as they respect the shared space.

Some other cafe franchises even cater to them with power outlets, individual desks and longer stay allowances.

Cafe owner Hyun Sung-joo isn't against Cagongjok but finds some customers take it too far

But others have taken stricter steps. Kim, a cafe owner in Jeonju who asked the BBC to remain anonymous, introduced a "No Study Zone" policy after repeated complaints about space being monopolised.

"Two people would come in and take over space for 10. Sometimes they'd leave for meals and come back to study for seven or eight hours," he says. "We eventually put up a sign saying this is a space for conversation, not for studying."

Now his cafe allows a maximum of two hours for those using it to study or work. The rule does not apply to regular customers who are simply having coffee.

"I made the policy to prevent potential conflicts between customers," Kim says.

'Cagongjok' - here to stay?

Yu-jin Mo feels more comfortable in cafes than in libraries

So what's behind the trend and why do so many in South Korea feel the need to work or study in cafes rather than in libraries, shared workspaces or at home?

For some, the cafe is more than just an ambient space; it's a place to feel grounded.

Yu-jin Mo, 29, tells the BBC about her experience growing up in foster care. "Home wasn't a safe place. I lived with my father in a small container, and sometimes he'd lock the door from the outside and leave me alone inside."

Even now, as an adult, she finds it hard to be alone. "As soon as I wake up, I go to a cafe. I tried libraries and study cafes, but they felt suffocating," she says.

Later Ms Mo even ran her own cafe for a year, hoping to offer a space where people like her could feel comfortable staying and studying.

Professor Choi Ra-young of Ansan University, who has studied lifelong education for over two decades, sees Cagongjok as a cultural phenomenon shaped by South Korea's hyper-competitive society.

"This is a youth culture created by the society we've built," she tells the BBC. "Most Cagongjok are likely job seekers or students. They're under pressure - whether it's from academics, job insecurity or housing conditions with no windows and no space to study.

"In a way, these young people are victims of a system that doesn't provide enough public space for them to work or learn," she adds. "They might be seen as a nuisance, but they're also a product of social structure."

Professor Choi said it was time to create more inclusive spaces. "We need guidelines and environments that allow for cafe studying - without disturbing others - if we want to accommodate this culture realistically."

Related topics

More Weekend Picks

- Published9 March