'She found a hellhole and called for reform'

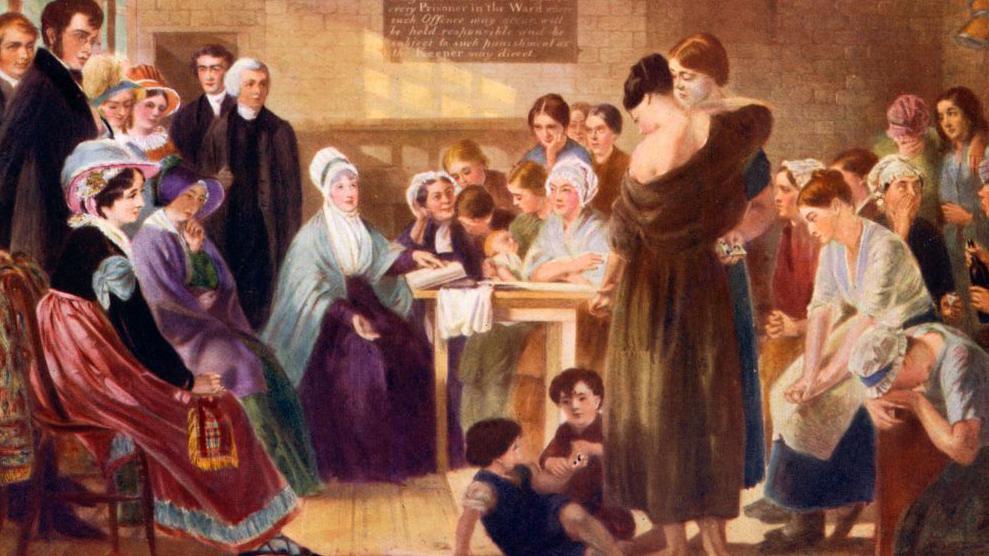

Elizabeth Fry was accompanied by friends on her first Newgate visit in 1813 and came with provisions for the inmates, but she was horrified by the experience

- Published

Prison isn’t working for women, according to Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood, while prisons minister James Timpson has said he sees “lots of very ill women” on visits.

More than 200 years ago, Elizabeth Fry felt the same way, after being deeply shocked by her visits to Newgate Prison in London.

The Quaker philanthropist spearheaded a campaign that resulted in women-only prisons superintended by female guards, treated inmates with humanity, and emphasised rehabilitation.

So, while ministers consider changes to the criminal justice system for female offenders, external, what can be learnt from the Norwich-born 19th Century reformer?

'A bunch of wild beasts'

Her prison reform activism was inspired by her membership of the Society of Friends or Quakers, who interpret Christianity to mean "all are equal before God"

Fry first visited Newgate Prison in 1813 and discovered "an absolute hellhole", according to Prof Rosalind Crone from the Open University, based in Milton Keynes.

"The guard said, 'I don't think we can let you go in, they're a bunch of wild beasts, they'll steal your valuables'," said the history professor.

"But she went in and saw some terrible sights, recorded in her journal, including women taking the clothes of a dead baby to give them to another living one."

Many of the women, who were not segregated from male prisoners and were awaiting deportation to Australia, were drunk and violent.

Some had their children with them; others delivered babies while in prison.

"When she returned in 1816, women were now separated from men, but the conditions were still dire, and she decided to open her Bible to read to them. They became quiet and listened," said Prof Crone.

"It gave her heart, and she came up with a plan for the prison - a way to structure it that she thought would be beneficial and would turn these 'wild beasts' into Christian women able to contribute to society - and give them peace as well."

'The men were flabbergasted'

An illustration based on a mid-19th Century painting, showing a largely fictionalised version of her Bible readings to women and child inmates and prison visitors

Elizabeth Fry's plan had three pillars, explained Prof Crone.

Superintendence: Women prisoners should be looked after by female officers, supervised by a superintendent or matron, there should be no access to these women by men unless they were chaperoned by a female, and the system should be "watched over by moral and religious ladies like herself".

Occupation: Fry thought the prisoners needed to be doing something, such as sewing or knitting, and she used her contacts to sell their products outside Newgate, giving some of the earnings back to the women. She also set up a school to teach inmates reading, writing and arithmetic.

Religious instruction: She was convinced that if they opened up to God and repented, this would turn their lives around and help create a better society outside prison.

Yet she knew better than to present this plan to the City of London authorities who ran the prison.

Prof Crone said: "Instead, she works pretty much in secret to set things up in prison, having gone to the prisoners and got their agreement.

"She brings a band of ladies together, which she called the Ladies' Newgate Association, they train the matron and start bringing work to the prisoners and mentoring them.

"In April 1817, they brought in the authorities, and the men were absolutely flabbergasted at the change in the women: they were quiet, obedient and sober."

Her small rehabilitation home for former Newgate prisoners ensured they had employable "feminine skills" for domestic service, while the ladies' association helped the ex-offenders find employment.

Who was Elizabeth Fry?

She was remembered with the "Fry fiver", which was in circulation between 2002 and 2016, but is now discontinued

Fry was born into the wealthy Gurney family in 1780 and grew up at Earlham Hall, just outside Norwich.

Prof Crone said: "They were Quakers, and Elizabeth had what she described as an epiphany aged 17 and became devout."

On getting married and moving to London in 1800, she continued her philanthropic endeavours in between having 11 children.

"The idea that all are equal before God is absolutely essential to the Quaker faith, and that's very important in this story," said Prof Crone.

As a result, the Society of Friends, or Quakers, treated women near-equally, with Fry later becoming one of their ministers.

Prof Crone said: "That also means that for prisoners, or the poor, there's a kind of equality before God, though that is not necessarily equality in society."

This affluent and activist evangelical Christian background gave her access to a network of other influential philanthropists at a time when prison reform was rising up the political agenda.

'An outsized influence on the law'

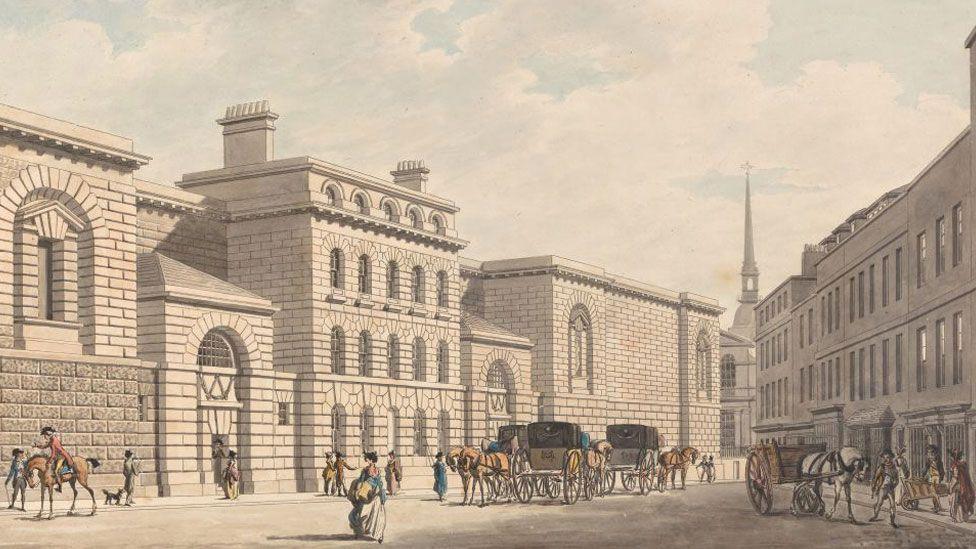

Newgate Prison was where prisoners were held for trial or after sentence in the early 19th Century

Fry toured the country with her campaign for women's prison reform, encouraging the establishment of many local prison visiting associations.

She became one of the first women to be called to speak to a parliamentary inquiry, giving evidence on prisons in 1818.

Prof Crone said: "And when the 1823 Gaols Act comes out, there's a clause about women being separated from men and also women being superintended by female officers."

She believes Fry's campaign for a women-centred system, which treated women differently from male prisoners, had "an outsized influence on that legislation" - and goes wider than that.

"I just think it's remarkable, because you see it just spreading through society, it then becomes a thing in hospitals too - that women should be taken care of by women, or there should be some kind of female chaperone present - is something we take for granted now when we go to the GP," she added.

Are there 19th Century lessons?

The philanthropist went on organise homeless shelters and established a national system of libraries for coastguard men and their families, as well as the Institution of Nursing Sisters in 1840

Prof Crone said: "In the beginning of the 19th Century, women were expected to be more virtuous than men, so female criminals were considered really deviant, and the purpose of Fry's rehabilitation regime - and those that followed - was to re-feminise women.

"Then female criminality is tied to female biology - mania, menstruation, menopause - and by the end of the century, women criminals are seen as feeble-minded or mentally ill, and that becomes the way of dealing with women's criminality.

"The lesson of the 19th Century and Fry is that our ideas of what a woman should be shape the regime in a woman's prison - and sometimes that is not a regime that allows women to flourish."

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Norfolk?

Follow Norfolk news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

- Published6 October 2024

- Published6 October 2024

- Published11 July 2024