Vaginal mesh degrades within 60 days - study

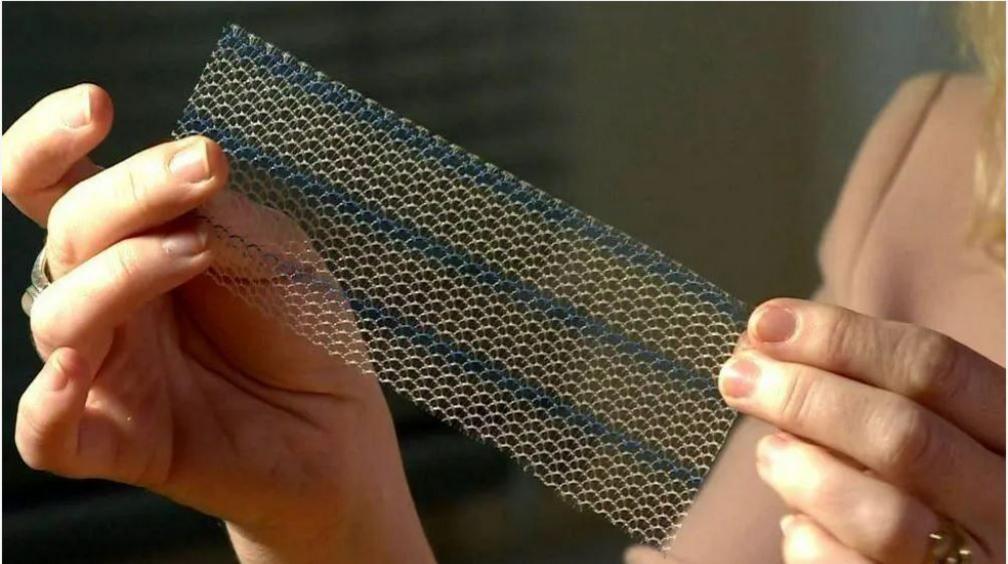

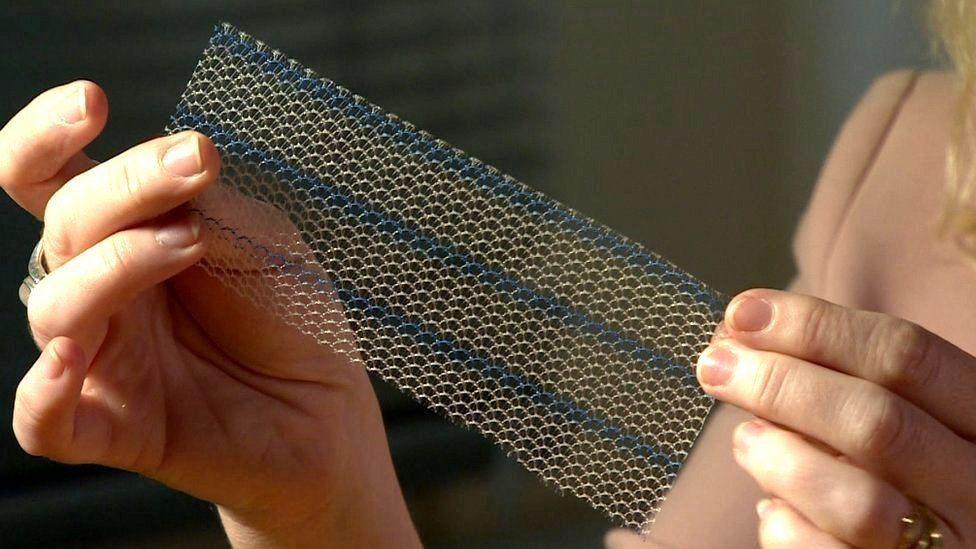

Vaginal mesh implants are made of polyproylene and can "shatter lives", campaigners say

- Published

A material commonly used in vaginal mesh implants starts to degrade within 60 days of being implanted in the pelvis, according to a new study.

Research by the University of Sheffield found traces of polypropylene, a type of thermoplastic, in the tissue surrounding implant sites.

Sheila MacNeil, emeritus professor of biomaterials and tissue engineering, said the findings meant it was "crucial" that "new and better" materials were found.

Dr Alison Cave, chief safety officer at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency said: [The] MHRA keeps devices under continuous review and we assess all new and emerging evidence."

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) implants - made from synthetic materials such as polypropylene - have been used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, but can cause debilitating harm to some women.

Side effects have included infection, pelvic pain, difficulty urinating, pain during sex, and incontinence.

The NHS restricted its use of TVM implants in 2018 and they are now used only as a last resort through a high-vigilance programme of restricted practice.

The study looked at polypropylene mesh implanted in sheep, which share a similar pelvic anatomy to women.

Prof MacNeil said: "This research provides objective physical evidence that this material does not cope well with implantation in the pelvis.

"This is crucial because it is imperative that we develop new and better materials for the many thousands of patients suffering from stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse."

It comes after more than 100 women in England with complications from vaginal mesh implants were given payouts as part of a group settlement.

Campaigners have now called for immediate action based on the Sheffield study.

Kath Sansom, founder of the support group Sling The Mesh, which has almost 11,000 members around the world, said: "The mesh-injured community have endured debilitating complications, unaware that the plastic material implanted in their bodies is not fit for purpose and could degrade so quickly.

"This study confirms what many of us have suspected - that the mesh becomes unstable, causing harm that is irreversible."

Dr Cave from the MHRA said: "Patient safety is our top priority and the use of surgical mesh to treat stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse has been subject to restrictions since July 10 2018.

"Exceptions are made in cases where this type of mesh may be the only treatment option that is right for a woman.

"However, it should only be used for carefully selected patients who have been informed of, and understand, the benefits and risks, and where all other treatment options have been explored."

Listen to highlights from South Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, catch up with the latest episode of Look North or tell us a story you think we should be covering here, external.

Related topics

- Published19 August 2024

- Published18 April 2017