'I solved the mystery of an Elizabethan card trick'

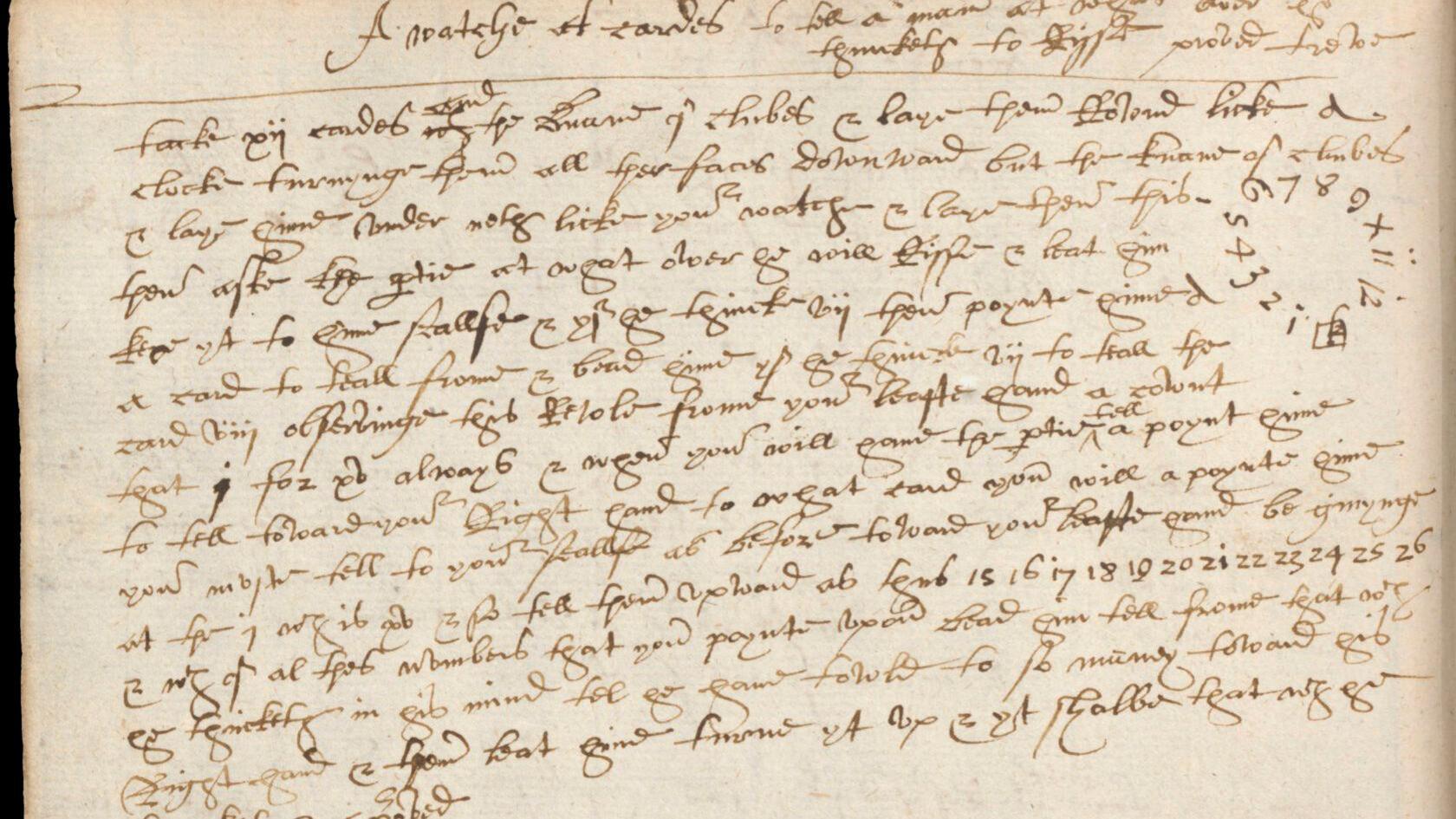

Philip Henslowe wrote down the instructions for the trick in his diary

- Published

More than four centuries ago, a Shakespearean theatre owner in London noted down the instructions to a card trick in his accounts book.

It described a routine where the performer could reveal a secret number chosen by a volunteer ... except it did not work.

The elaborate handwriting and archaic language already made it difficult to understand and a 19th Century transcription did not help.

With the trick almost lost, a mathematician from Weymouth began investigating and has now solved the mystery, with the help of his 11-year-old son.

Colin Beveridge, who describes himself as a freelance mathematician, learned about the trick from his friend, maths historian Rob Eastaway, who came across it while writing a book about the mathematics of Shakespeare.

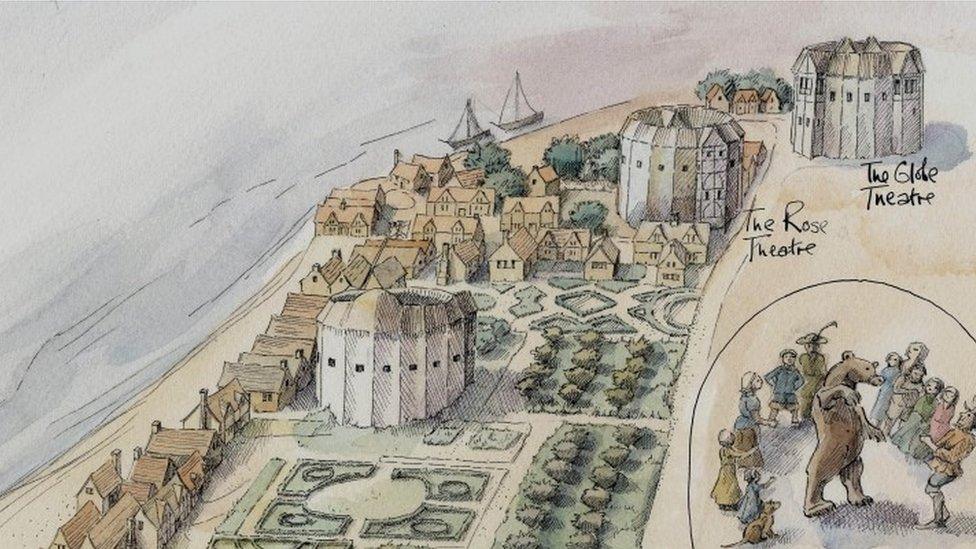

It was described in the 1590s by Philip Henslowe, an entrepreneur who built and owned the Rose Theatre on London's Bankside.

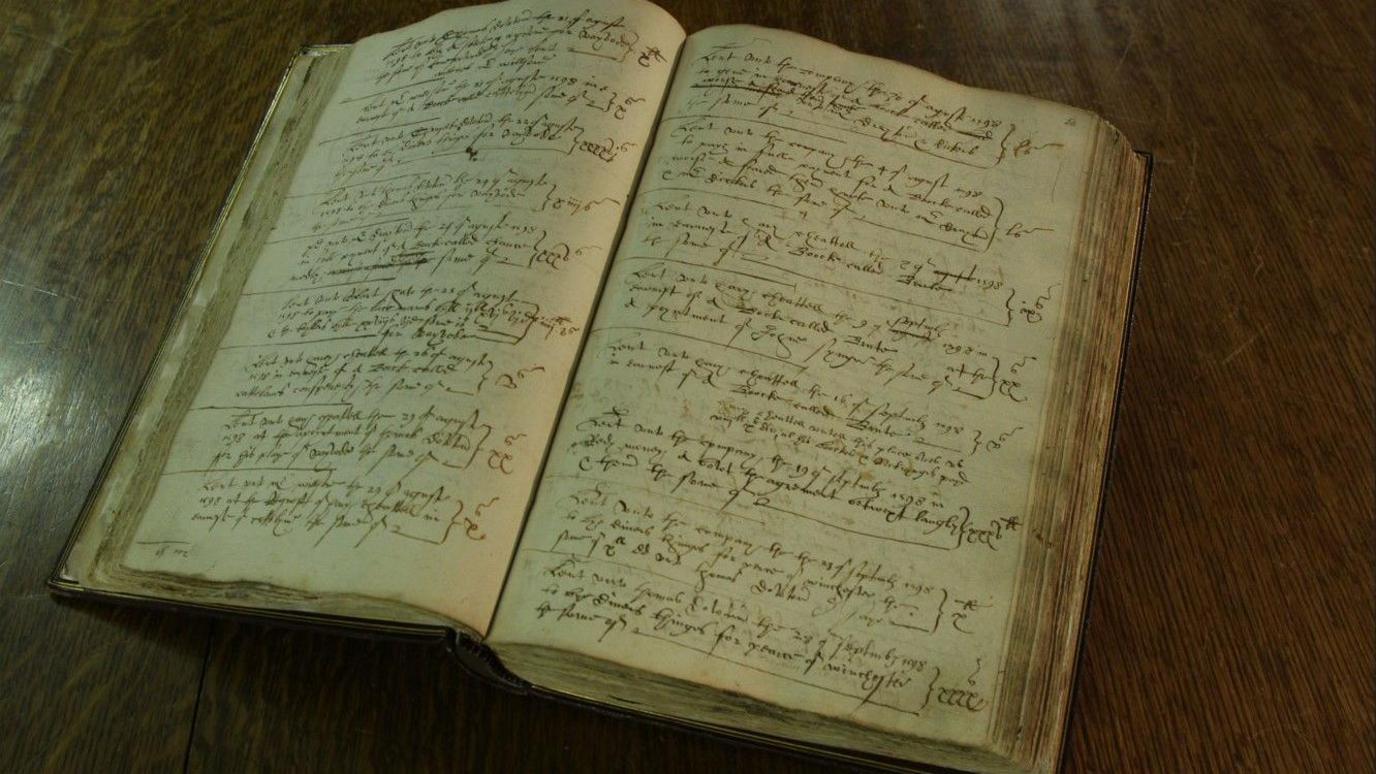

Henslowe's notebook - later published as the Diary of Philip Henslowe - served as a record of the theatre's accounts, which included performances of Shakespeare's plays.

Colin Beveridge sat down with a pack of cards in a bid to solve the puzzle

"In among all the theatre accountancy, there's this card trick," said Mr Beveridge.

"It's written in Shakespearean English so it's difficult to understand.

"Rob asked me if I could make sense of it."

It fascinated Mr Beveridge because most of the card tricks from the Elizabethan era were based on sleight of hand rather than calculations.

According to the 19th Century transcription, the performer lays out a circle of 13 cards - ace to queen - followed by the jack of clubs face-up.

The volunteer is asked to think of a number from one to 12 and a card in the circle, keeping both secret.

Henslowe's book listed theatre accounts, including those of Shakespeare's plays

By counting clockwise and anticlockwise from their chosen card, under the direction of the performer, the volunteer ends up turning over the card showing their secret number.

But, no matter how it was performed, the trick seemed to end in disappointment.

"There were two sides to understanding it – the maths and the English," said Mr Beveridge.

"It was a case of sitting down with a pack of cards and figuring out what might work."

After explaining his new theory to his maths-savvy son, the pair were able to devise a simpler explanation, which Mr Beveridge shared on the Aperiodical, external maths blog.

He said: "Quite often when I'm writing something that is public-facing, I will explain it to my son and he will ask questions that help me refine it, so he is a good person to go to."

Get in touch

Do you have a story BBC Dorset should cover?

You can follow BBC Dorset on Facebook, external, X (Twitter), external, or Instagram, external.

- Published1 November 2024

- Published14 March 2024

- Published26 September 2016