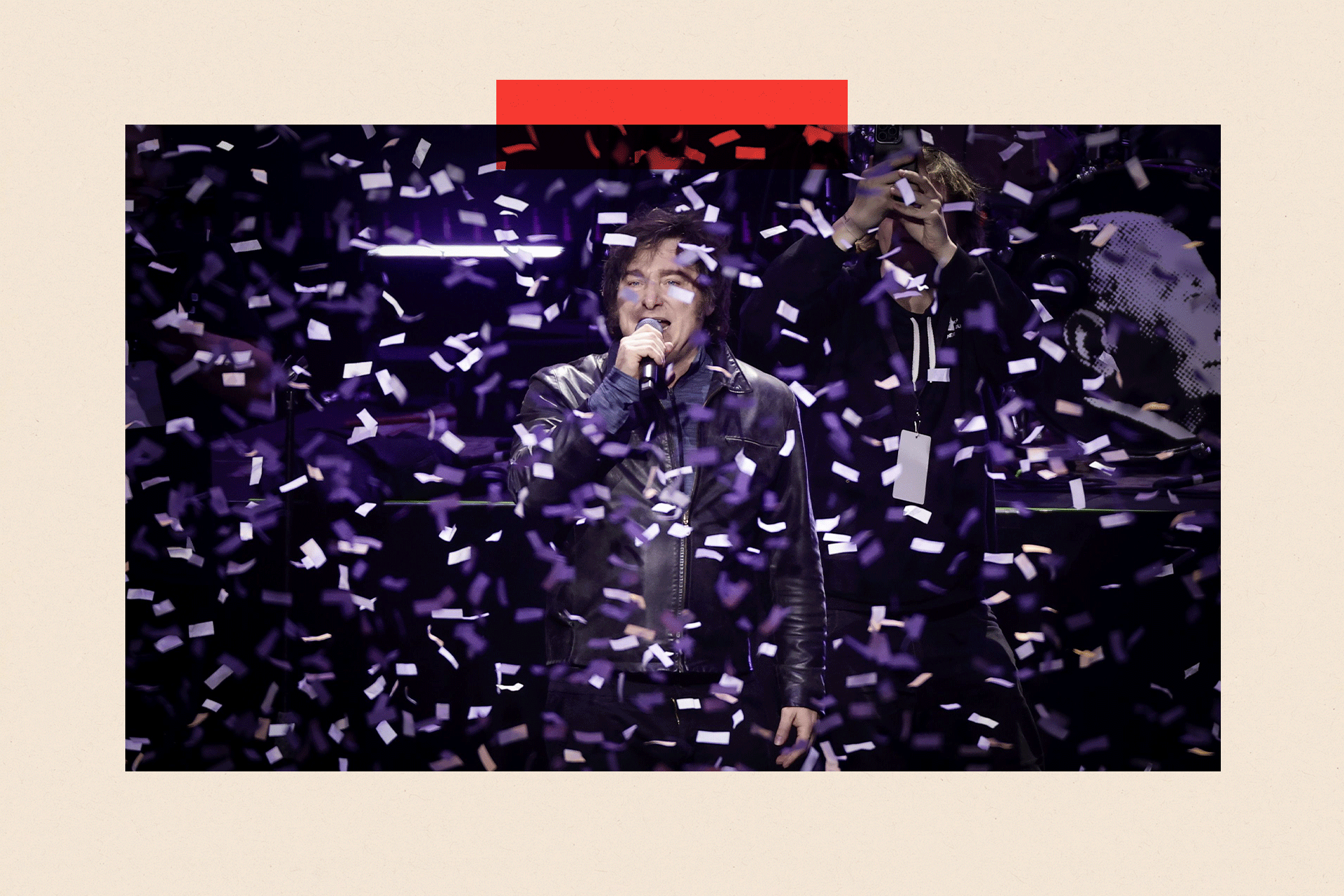

Buenos Aires, September 2023. Hundreds of people crowded around to wave flags and film on their phones. The man with unruly hair and sideburns in the centre of them, clad in a black leather jacket, hoisted a roaring chainsaw above his head.

This was an election rally taking place in the San Martín area of the Argentine capital a month before the presidential election - and the metaphor was explicit.

The candidate Javier Milei believed the state was far too bloated, with annual debts that were bigger than Argentina's entire annual economic output.

Rather than 'trimming the fat', as some politicians delicately put it, he said he would take a chainsaw to ministries, subsidies and the ruling political class he derided as "la casta" - the caste.

Javier Milei's election rallies featured an unusual prop

Milei had form for stunts. In 2019, he dressed up in a "libertarian superhero" costume, purporting to be from Liberland - a land where no taxes are paid. In 2018, he smashed a piñata of the Central Bank on live television.

According to official data, inflation in 2023 topped 211% annually - Milei took office in December of that year. Roughly 40% of the population lived in poverty. Years of high public spending, and a reliance on printing more money and borrowing to cover deficits, had left the country in a cycle of debts and inflation.

Yet nearly two years on, the headline figures are vastly different: Argentina recorded its first fiscal surplus in 14 years and inflation, which had hit triple figures annually, has tumbled to roughly 36%.

The UK Conservative party leader Kemi Badenoch called the measures Milei has taken a "template" for a future Conservative government. And in the US, President Donald Trump described Milei as "my favourite president".

They will meet in Washington on Tuesday.

Donald Trump has described Milei as 'my favourite president' - they are due to meet at the White House later today

Foreign investors regained confidence in Argentina too. Although that recently slipped, Washington's decision last week to swap $20bn (£15bn) in dollars for pesos, effectively propping up Argentina's currency with International Monetary Fund (IMF) backing, is a sign Milei's fiscal shock therapy has appeased international lenders. Trump and Milei's meeting will hail the deal.

Yet for all the international praise, this is just one side of the story. On the streets there have been heated protests over Milei's reforms, with police firing tear gas, rubber bullets and a water cannon during clashes.

"He said in his campaign that this adjustment would be paid for by 'la casta' – the wealthy, the politicians, the evil businessmen," says Mercedes D'Alessandro, a left-wing economist and senate candidate.

But, she argues, the result was less money for pensioners and hospitals. "The adjustment in the end was directed at the working classes, not the caste."

Milei's reforms have prompted heated protests

Milei's critics argue that the price of his changes have been recession, job losses, weaker public services and declining household budgets. And now some economists say the country could be about to enter a recession.

Milei has created a paradox.

On paper, his chainsaw has achieved some of the macroeconomic successes he set out to do. But Milei has lost political support and that has spooked the markets, which in turn has destabilised his economic project.

With midterm elections looming on 26 October, Argentina is about to deliver its verdict: will Milei be punished for doing what he set out to do — and could losing political support completely unravel his economic gains?

Argentines feeling the cost

Around 700 miles from the capital in the Misiones province, tea farmer Ygor Sobol looks anxious. "We're all going backwards economically," he says. "I had to close the payroll. Now I am completely without employees."

For three generations his family has grown yerba mate, a drink popular with Argentines, but since Milei deregulated his industry by scrapping minimum prices, he says that his crops have become worth less than the cost of producing them.

Now, Mr Sobol says he can't afford to do basic tasks like cleaning and fertilising his plantation. And with the business making a loss, he's deciding what his family will have to go without too.

For all the international praise since Milei was sworn in (pictured), this is just one side of the story

Argentina's multibillion dollar textile industry is also affected. Luciano Galfione, chairman of a non-profit for the sector Fundacion Pro Tejer, describes "daily" closures and job losses.

Unlike Trump's approach of raising tariffs to promote "America First", Milei cut tariffs and other criteria for imports.

"I have environmental controls, labour controls - we don't pay people $80 (£60) a month, or have 16-hour work days that might be allowed in places like Bangladesh or Vietnam. This creates an unequal playing field," Mr Galfione argues.

He believes that boosting imports has battered domestic producers. "Our sector lost more than 10,000 direct jobs. If you add indirect jobs, there are many more."

Mr Galfione also blames rising costs of utilities, health and schools for reducing the disposable income of average people, and in turn making them less likely to buy clothes.

And yet amid it all, Milei is adamant that his measures will improve the lives of ordinary Argentines.

'Everything was a huge mess'

In the run-up to the election Milei had said there was no alternative to big cuts.

As well as the soaring inflation, vast government subsidies had kept energy and transport prices down. Public spending was high, even before the Covid-19 pandemic. Price controls set fixed prices for certain goods. Argentina, still, owes £31bn in debt to the IMF.

"The demand for public spending was brutal," argues Ramiro Castiñeira, an economist at the consultancy Econométrica who supports Milei.

"Society seemed willing to live with so much inflation. Or didn't recognise that inflation was a product of so much public spending."

Opponents of Javier Milei say ordinary people have been left with less disposable income

Inflation ate away the peso currency's purchasing power. Many ordinary Argentines handed over disproportionate sums of pesos to illegal street traders to buy dollars, fearing their money would lose value overnight.

"Everything was a huge mess," explains Martin Rapetti, an economics professor at the University of Buenos Aires and executive director of think tank Equilibria.

"People felt money slipping like water through their fingers."

For many economists, drastic change (even if painful) was essential to restore credibility. And Milei promised radical change.

He went viral for ripping government ministries such as Culture and Women off a whiteboard while shouting 'afuera!' - 'out!'

Among other austerity measures, he halved government ministries, cut tens of thousands of public jobs, slashed budgets including for education, health, pensions and infrastructure, and removed subsidies – spiking utility and transport prices.

His initial devaluing of the peso by 50% caused inflation to spike but then it fell as people spent less and demand fell.

Milei's supporters credit him with taming Argentina's previously rampant inflation

'Echoes of Thatcherism'

When I met him in April 2024 at his office, there were sculptures of him with a chainsaw on display and coasters showing Margaret Thatcher's face. Thatcher is loathed by many people in Argentina owing to the Falklands War, but Milei told me he admired her and that she was "brilliant."

Last month one British newspaper described Milei's own approach as having "echoes of Thatcherism".

Miguel Boggiano, an economist on Milei's economic advisory board, is full of praise for Milei getting inflation down and reducing the deficit. "When you bear in mind the starting point, that's a huge accomplishment," he says.

Javier Milei's reforms have drawn comparisons with those of Margaret Thatcher

He believes this will help alleviate poverty in the long-run and enable lower taxes, but also help people to plan their own spending more easily with inflation currently fluctuating less.

But Alan Cibils, an independent economist and former professor, warns reduced inflation is only a success if it is sustained over time which he believes will not be the case.

The outsider advantage

Javier Milei is not a career politician. Before becoming president he had two years experience as a deputy in Argentina's Congress.

"Being so detached kind of shields him," Prof Rapetti observes, citing a lack of "signs of empathy in public life".

On 7 September Milei's party lost unexpectedly badly in the Buenos Aires provincial elections. His convoy was pelted with rocks on the campaign trail. The markets panicked: foreign investors sold off pesos and bonds of Argentine government debt.

Some observers say Milei displays a lack of empathy towards those affected by cuts

Financial markets had generally supported his economic programme. But the midterm elections were upcoming and the £15bn of debt repayments are due next year.

Trump's £15bn currency swap lifeline has provided some stability: Argentine bonds and the peso rose in value in response to the announcement. But D'Alessandro argues that though US intervention might solve a wider problem, nothing will change in "people's real lives".

"We're going to continue with no investment in hospitals, education, social programmes. This money from the United States is not going to improve Argentina's infrastructure."

Flawed leader or model for other countries?

Some of Milei's supporters - like Mr Boggiano - believe there is something else at play in the round criticism of the president: In this view much of it comes down to the opposition trying to "break" what Milei has done, in order to get back into power.

"Once everyone starts to believe stability is here to stay, investment will come back," says Mr Boggiano. "I think Milei will become a model for other countries."

Others are unsure. "There is some stability which helps things not to explode," said Mr Cibils. "But I think that stability is also a mirage."

Trump promised retribution - how far will he go?

- Published27 September

Milei had also kept inflation under control by spending the country's reserves on propping-up the peso so it didn't crash. Meanwhile, Argentina owes $20bn of debt next year.

One former central bank economist, who wished to speak anonymously, warns Milei's strategy of keeping inflation down could unravel if Argentina can't pay its debts.

"If at the end of the day we have a financial crisis that partially undoes all the effort, then it's a failure. If it ends with social unrest, any good done will be reversed," says the economist.

The left-wing governor of Buenos Aires, Axel Kicillof, has been touted as a future presidential candidate, long ahead of the elections in 2027. He has spoken in favour of the welfare state. Some investors are calculating whether this could mean a return to the days of big spending.

Buenos Aires governor Axel Kicillof has been touted as a future presidential candidate

As to the question of whether Milei has succeeded, the answer largely depends how you define success - and who it is for.

Many workers see shuttered factories, rocketing bills, and a vanishing safety net.

Meanwhile, some investors see a success story of fiscal discipline, tamed inflation, an ally in Washington and simply a "normalisation".

But even as leaders abroad watch Milei's experiment with fascination, politics may explain why few are unlikely to copy it.

If normal people lose faith in what he is doing, markets will also lose confidence that his programme is sustainable – and that could wipe out even the 'macro' successes.

"He has no political expertise, and I think you need it," Prof Rapetti argues.

Still, he believes it is too early to judge: "We are in the middle of his term… The story hasn't finished."

Top picture credit: WPA Pool/Getty Images, Bloomberg via Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can sign up for notifications that will alert you when a BBC InDepth story is published - find out how to sign up here.