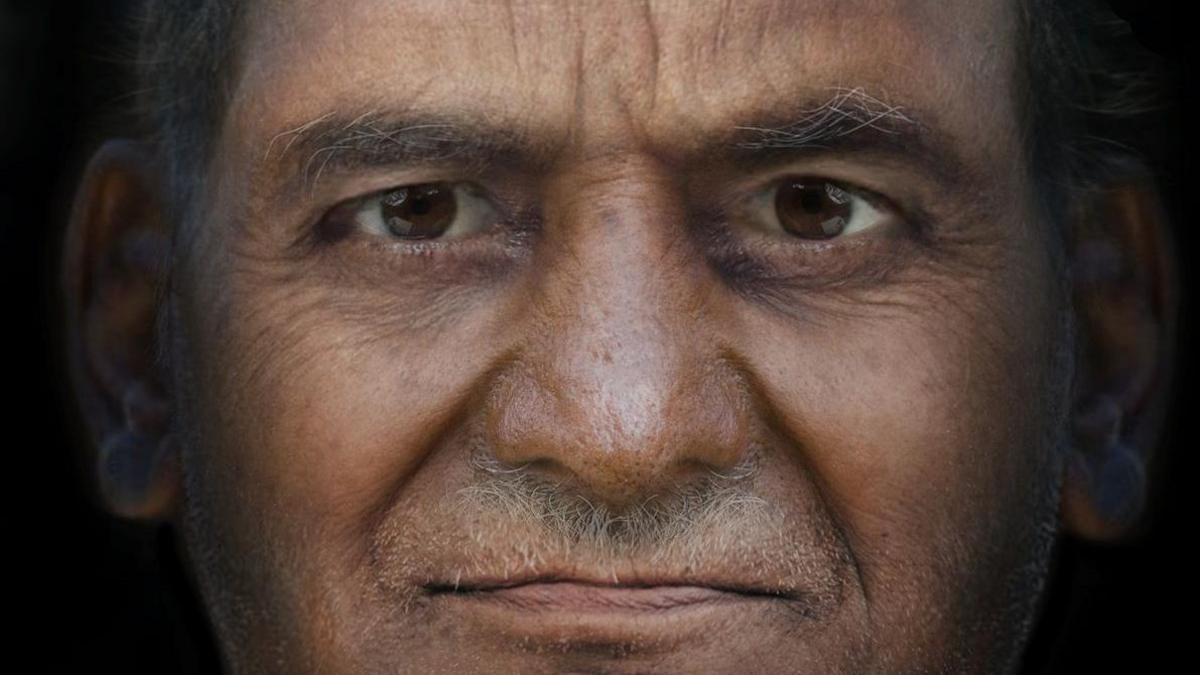

How researchers recreated faces of 2,500-year-old skulls found in India

The facial reconstruction of a 2,500-year-old skull excavated at Kondagai

- Published

In a modest-sized university lab in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, researchers are using a tiny drill to scrape away enamel from a 2,500-year-old tooth.

Researchers at Madurai Kamaraj University say the tooth belongs to one of two human skulls that they have used as models to digitally reconstruct faces to understand what the region's early inhabitants might have looked like.

The skulls, both belonging to men, were excavated from Kondagai, an ancient burial site about 4km (2.5 miles) from Keeladi - an archaeological site that has become a political flashpoint in India.

Tamil Nadu state department archaeologists say an urban civilisation dating back to 580BC existed in Keeladi, a claim that adds a new dimension to the story of the Indian subcontinent.

The Indus Valley Civilisation, that emerged over 5,000 years ago in the northern and central parts of present-day India, is the country's first major civilisation - and narratives around urbanisation have so far been confined to the north.

But state archaeologists say the findings at Keeladi indicate for the first time that an ancient independent civilisation existed in southern India as well.

They say the people of Keeladi were literate, highly-skilled and engaged in trade across the subcontinent and abroad. They lived in brick houses and buried their dead along with daily necessities like food grains and pots in massive burial urns in Kondagai.

Archaeologists have excavated about 50 such urns from the site so far.

Burial urns at Kondagai have been found to contain human remains and goods

Researchers at Madurai Kamaraj University are now extracting DNA from human bones and other goods found in these urns to better understand who the inhabitants of Keeladi were and what their lifestyle was like.

But a more profound quest seems to be under way.

"We want to understand our ancestry and the migration routes of our ancestors," says professor G Kumaresan, who heads the genetics department at the university. "It's a journey towards answering the larger question of 'who are we and how did we come to exist here'," he adds.

The exercise of reconstructing faces of the 2,500-year-old skulls has revealed clues that can answer at least one part of this question.

"The faces mainly have features of Ancient Ancestral South Indians - a population group believed to be the first inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent," says Prof Kumaresan.

The features also reveal traces of Middle-East Eurasian and Austro-Asiactic ancestries, hinting at global migration and the mixing of ancient population groups. But Prof Kumaresan says that more research is needed to properly establish the ancestries of Keeladi's residents.

The facial reconstruction of the skulls began with researchers at Madurai Kamaraj University creating 3D scans of the skulls.

These digital scans were then sent to Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK. Face Lab specialises in creating digital craniofacial reconstructions using forensic, artistic and scientific principles and technologies.

Experts at the lab used computer softwares to add muscles, flesh and skin to the scans of skulls, bringing out their facial features. These additions were made according to standard human anatomical proportions and measurements.

A researcher at work at the ancient DNA lab in Madurai Kamaraj University

Then came the big challenge: adding colour to the images.

This brought up questions like which shade of brown should the men be, what colour should their eyes have and how should their hair look?

Prof Kumaresan says the standard practice of using colours that matched physical traits of people currently living in Tamil Nadu was followed, but the digital portraits still evoked lively discussions on social media.

They underscored longstanding divisions in Indian society - around race, culture and heritage.

Historical narratives championing Aryans (a term commonly used to describe people who settled in the northern part of India) as the "original citizens" of the country clashed with those that ascribed this title to Dravidians (a term used to describe people living primarily in India's southern states).

India has always been plagued by a north-south divide that stems partly from the popular belief that Indian civilisation - and everything associated with it, like language, culture and even religion - took root in the north and shaped the rest of the country.

But Prof Kumaresan says the facial portraits of the Keeladi skulls reveal a message that's more complex and inclusive.

"The message we can all take home is that we are more diverse than we realise, and the proof of this lies in our DNA," he says.

This isn't the first time that researchers in India have attempted to recreate faces from ancient skulls.

In 2019, scientists reconstructed faces of two skulls found at a cemetery in Rakhigarhi - an important Indus Valley Civilisation site in India. But the sketches lack colour and other physical traits.

"As humans, we have a fascination with faces – our ability to recognise and interpret faces is part of our success as a social species," says Caroline Wilkinson, who headed the Face Lab team that worked on the Keeladi men.

"These facial depictions also encourage the audience to understand ancient remains as people rather than artefacts, and to establish a connection through personal narrative rather than a wider population history," she adds.

A digital portrait of the other skull excavated at Kondagai

At the Madurai Kamaraj University, efforts are under way to study Keeladi as thoroughly as the Indus Valley Civilisation.

"So far, we have learnt that the people of Keeladi were involved in agriculture, trade and cattle-rearing. They kept deer, goats and wild pigs and ate lots of rice and millets," says Prof Kumaresan.

"Interestingly, we have found evidence that they also consumed dates, even though the date palm isn't ubiquitous in Tamil Nadu at present," he adds.

But the most challenging task for his team remains extracting sufficient DNA from human skeletons found at Kondagai to create a gene library. Because the skeletons are badly degraded, the DNA extracted from them is low and of poor quality. But Prof Kumaresan is hopeful that some good will come out of these endeavours.

"Ancient DNA libraries are like portals to the past; they can reveal fascinating insights about life as it was and life as we know it to be," he says.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, external, YouTube, external, Twitter, external and Facebook, external.