My eye-opening day at overrun A&E department

We met patients who had been on trolleys in the emergency department for several days and staff said they found the situation upsetting

- Published

It's Thursday morning at Swansea's Morriston Hospital and both staff and patients face a grim day ahead.

Eight ambulances are queuing up outside, 85 patients are waiting for a bed and one patient has been sitting on a hard plastic chair for 44 hours.

We're here to witness the inner working of the hospital, how staff are working flat-out to keep the system moving and the impact it is having on patients.

We'll meet some patients who have spent several days in the hospital's busy, noisy, windowless emergency department where the bright lights stay on 24 hours a day.

Among them are Simon Morris, who has been on a trolley for four days with cellulitis in his legs.

Also here is Natalie Lamb, who's been on a trolley since Monday while being treated for a blood clot.

Meanwhile, one of the senior nurses we speak to admits he is no longer able to give the fundamentals of care to all patients, a predicament he says is upsetting to staff.

Another member of staff tells us the challenge feels insurmountable.

Husband died 'in a state' after ambulance no-show

- Published23 January

'I thought I would die waiting for an ambulance'

- Published31 December 2024

On arrival at the hospital we are issued our face masks and led down what feels like a never ending rabbit's warren of corridors until we reach a small room, which essentially acts as the control centre for the hospital.

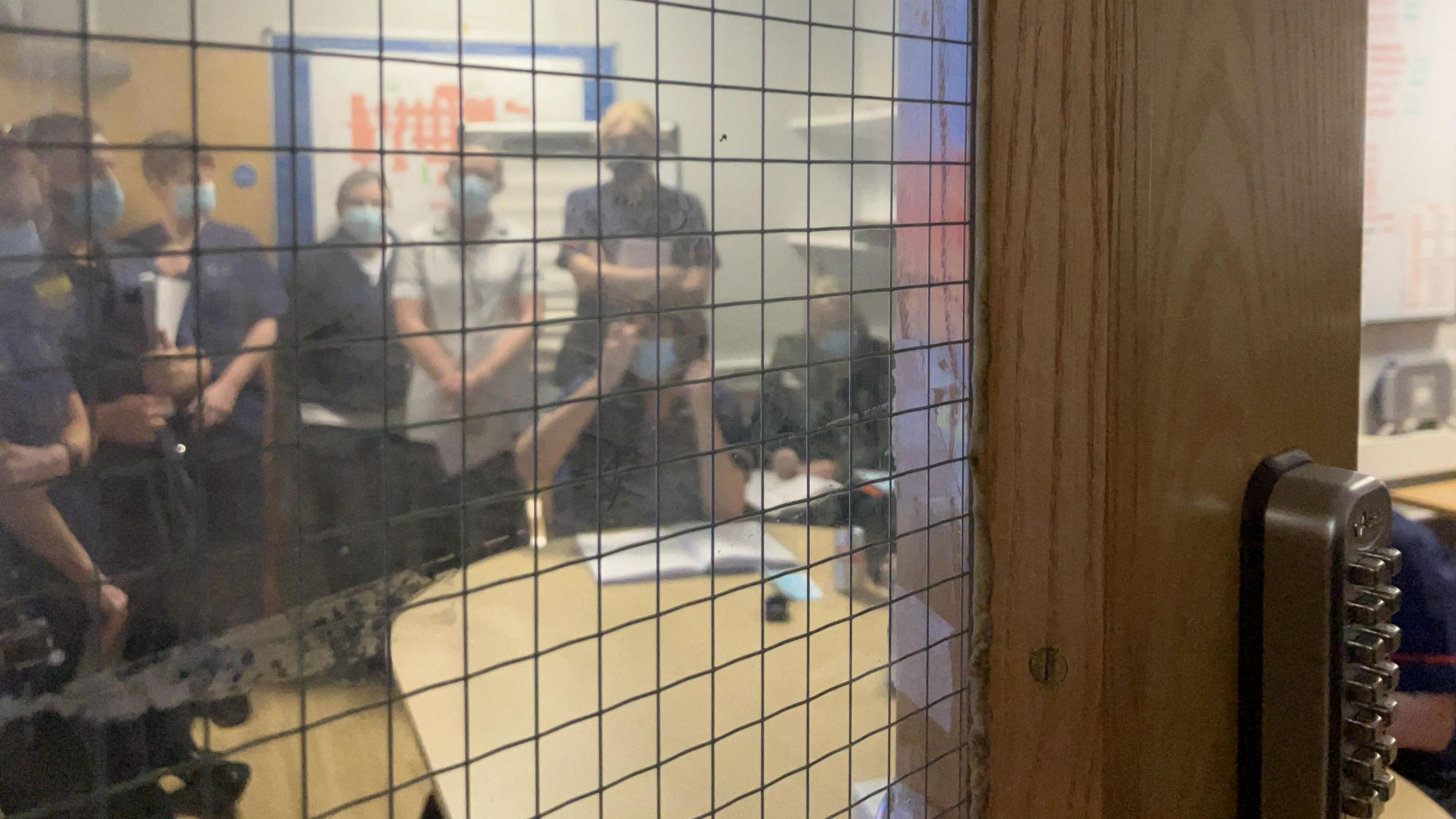

At 09:00 [GMT] the meeting begins and about 20 members of staff each succinctly outline the particular challenges their department faces that day - everything from the number of patients waiting for beds, staff sickness and any hold ups discharging patients who are well enough to go home.

Each day at the hospital begins with a meeting where staff outline the particular challenges their department faces that day

The meeting is chaired by head of patient flow Callum Allen-Ridge.

"You're constantly trying to assess what's happening but also predict the other sides of the puzzle where you can't really see what's happening yet," says Callum.

"It's a bit like trying to solve a Rubik's cube that's trying to fight back against you."

Head of patients flow Callum Allen-Ridge says the task of getting patients to where they need to be can feel insurmountable

During the meeting we learn one patient has been waiting on a trolley in the emergency department for 139 hours - more than five-and-a-half days.

Another patient is well enough to go home but can't leave because he does not have his house keys.

Callum admits sometimes coming into work in the morning felt daunting.

"The task can seem insurmountable," he says.

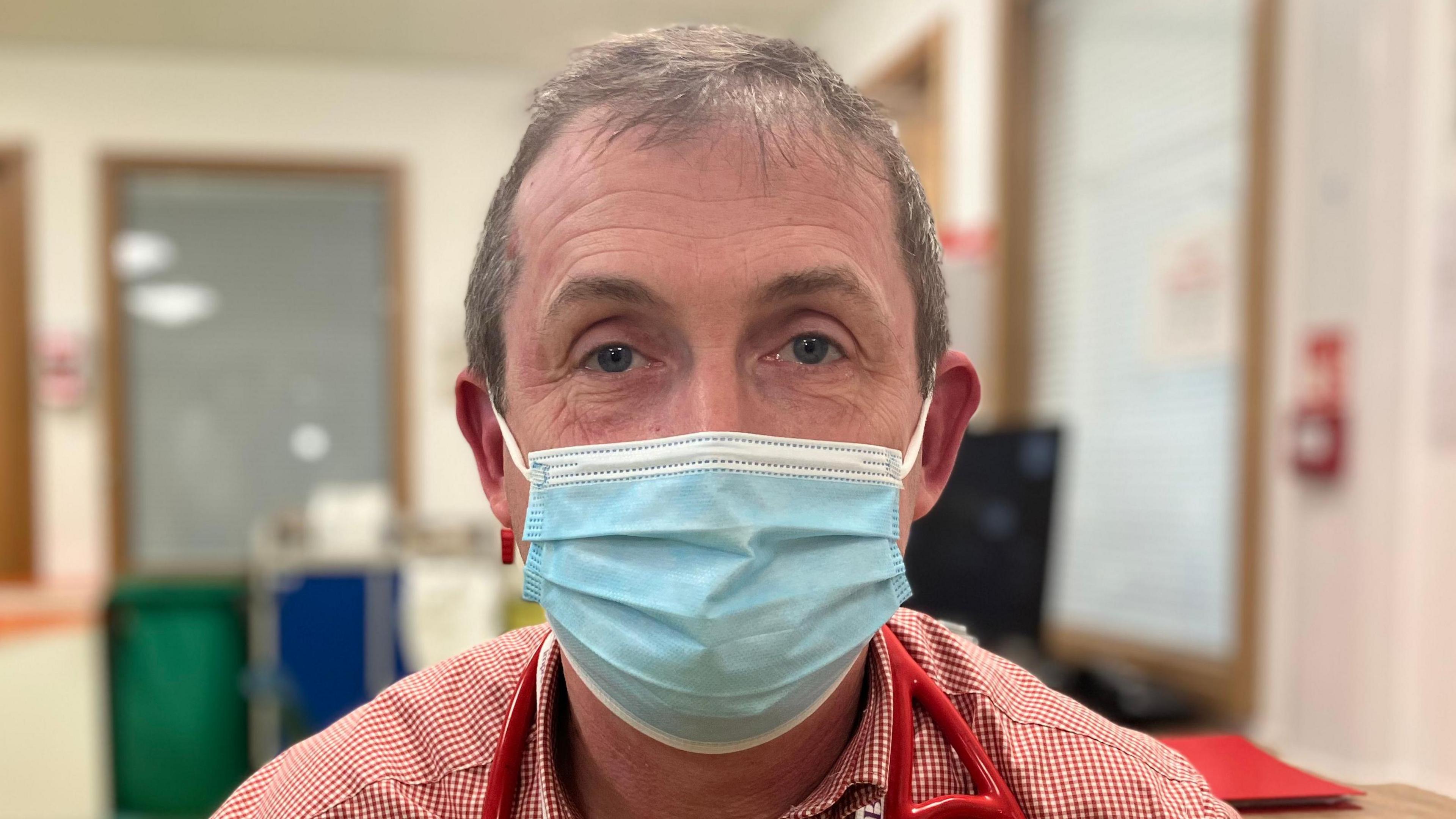

Consultant geriatrician Rhodri Edwards says hospital staff are under a huge amount of stress

After the morning meeting a video call meeting is held with Swansea Bay University Health Board's other hospitals before we are given the opportunity to meet more staff.

Consultant geriatrician Rhodri Edwards describes the pressure on the hospital as "unrelenting".

"I think staff are very stressed, I think they feel quite demoralised and I think there is a real high risk of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and therapists facing burnout because of the pressures that they're under to do their jobs," he says.

"I think everybody's very highly committed and really working hard to deliver the best outcomes for patients, but I think they really struggle with some of the challenges that they're facing, particularly working in overcrowded areas, looking after patients in really busy departments."

Dr Edwards, who is one of the associate medical directors for acute and scheduled care, says having to treat patients in unsuitable areas sometimes leads to issues around privacy and dignity.

"People are being asked to do things that they don't feel particularly comfortable about... I think that causes a huge amount of stress and moral injury to some of the staff," he says.

Chloe Lancey has been a paramedic for 20 years and says in that time the job had changed dramatically

Outside the hospital's A&E entrance, ambulance paramedic Chloe Lancey is feeling frustrated.

She says only last week she brought a patient to the hospital by ambulance, left them waiting in the ambulance at the end of her shift and found they were still there when she returned the following day.

"It's awful, it's sad," she says.

"It's not the job that we signed up to do. We should be out there helping people and we can't get to them because we're here."

In the afternoon we are taken to see the hospital's emergency department.

As a bystander, being in the overcrowded, windowless space is anxiety-inducing.

Some patients are lined up in beds, others sit on plastic chairs with staff dashing all around.

"It's a noisy and busy environment with no windows and where the lights never go off," says Callum.

"It's quite easy for patients who are quite unwell to get disorientated in an emergency department which then complicates their recovery and the outcomes for their care."

Tristan Taylor speaks to BBC Wales health correspondent Owain Clarke

"It makes us upset. I didn't come into nursing to give a standard of care like this," admits Tristan Taylor, the department's senior charge nurse.

Looking around the space, he adds: "Unfortunately when you haven't got the flow in the hospital - this is what we end up with.

"I can't give the fundamentals of care to all patients - because we physically can't.

"We do the best we can do for the patient, but obviously the best isn't good enough."

Natalie Lamb (right) is being treated for a blood clot on a trolley in the hospital's emergency department

Natalie Lamb was sent to A&E by her GP after experiencing shortness of breath.

After waiting for two hours in a chair in the waiting room she was told she had a blood clot, spent the night in resus before being moved to a trolley in the emergency department where she is spending her third day.

She has a lot of sympathy and admiration for staff and had seen them being yelled at by frustrated patients.

"They're run off their feet trying to see everybody, they're overrun and have nowhere to put anyone," she says.

"Something needs to be done about it."

Her partner Karen Davies says politicians need to better understand the situation.

"It's an eye-opener, it's disgusting," she says.

Simon Morris had been on a trolley in the emergency department for four days with cellulitis in his legs

Simon Morris has been on a trolley in the busy emergency department for four days after being brought in by ambulance with cellulitis in both legs.

He says he is grateful to have been moved from the corridor into a bay.

"I'd rather be stuck here than be stuck out in the corridor, because in the corridor you have a lot of people hitting into you, bumping you and they all apologise," he says.

"The staff have been brilliant to me... I've seen doctors and nurses running left, right and centre."

Nathan Davies was referred to Morriston's same day emergency care unit by his local out-of-hours service after tearing his patellar tendon and ligament in a fall

Things the hospital is doing to try and overcome the issues

Virtual wards, external: The health board says by making the patient's own bed at home part of a "virtual ward" they can still offer hands-on care with multidisciplinary team involvement while reducing avoidable hospital admissions and preventing deconditioning the risk of picking up hospital infections.

Integrated discharge hub, external: Launched in July 2024, a dedicated team works with third sector, local authorities and health board services to resolve obstacles that delay discharge for patients. The team deals with about 20 referrals a day.

Same day emergency care unit: This service allows patients to be assessed, diagnosed, and treated on the same day they arrive at the hospital after being referred by their GP reducing the number of patients who end up in the emergency department.

Ambulance pod: Outside the hospital's emergency department there is a pod that provides a safe and comfortable environment for patients who may have otherwise been cared for in the back of an ambulance.

Clive Donavan (pictured with his wife Anne) was taken to the pod after being brought to hospital by ambulance with inflammation of the pancreas

What's causing the problem? Analysis by Health Correspondent Owain Clarke

Although I've visited many A&Es over the years - the scenes we witnessed at Morriston were some of the most striking I've ever encountered.

Staff worry a lot about having to treat patients in open spaces - it's not dignified and comes with many risks.

But when so many ambulances with patients are stuck outside, unable to respond to emergencies, you can see why they end up using every inch of capacity.

We clearly saw a system struggling to cope with the huge and growing health demands of an ageing, but also relatively sick and poor population.

On one level it's a simple equation - A&E becomes overcrowded when more people come into the hospital than leave.

It's no surprise that efforts are focused on preventing, where possible, patients from coming in or getting them out of hospital more quickly afterwards.

But both little things (the patient without keys) and big things (an infection outbreak at a nearby elderly care hospital) can throw spanners in the works.

There's also an appeal to families to help get loved ones home if they can - even if it's inconvenient - as only a handful of extra discharges on any day can prevent a difficult day from becoming a horrendous one.

Don't forget either - the pressures on the NHS are made worse by deep-seated challenges in social care.

One A&E consultant told me, given how many patients were flowing in, it felt like the walls of her department were made of elastic.

Some will wonder how much further that elastic can be stretched before it snaps.

The Welsh government urged patients to access the right care in the right place.

"Enabling people who need admission to hospital to leave when they are ready is fundamentally important for better outcomes, experiences and to enable timely flow of patients from emergency departments and ambulance vehicles," a spokeswoman said.

She said the Welsh government had invested more than £180m in additional funds this year to help safely manage more people in the community, avoid ambulance transport and admission to hospital.

Last November it launched a 50-day challenge to help speed up the hospital discharge process and she said the initial results had been encouraging.

- Published23 January

- Published17 September 2024

- Published23 January