UK taxpayers no longer own NatWest - but 17 years on, are banks safer from collapse?

- Published

- 1124 Comments

The Treasury has announced the sale of its final shares in the NatWest Group. It means the bank will be under full private ownership, almost two decades after it was bailed out by the taxpayer amid the 2008 financial crisis.

This marks a symbolic end to a dramatic chapter in British banking history.

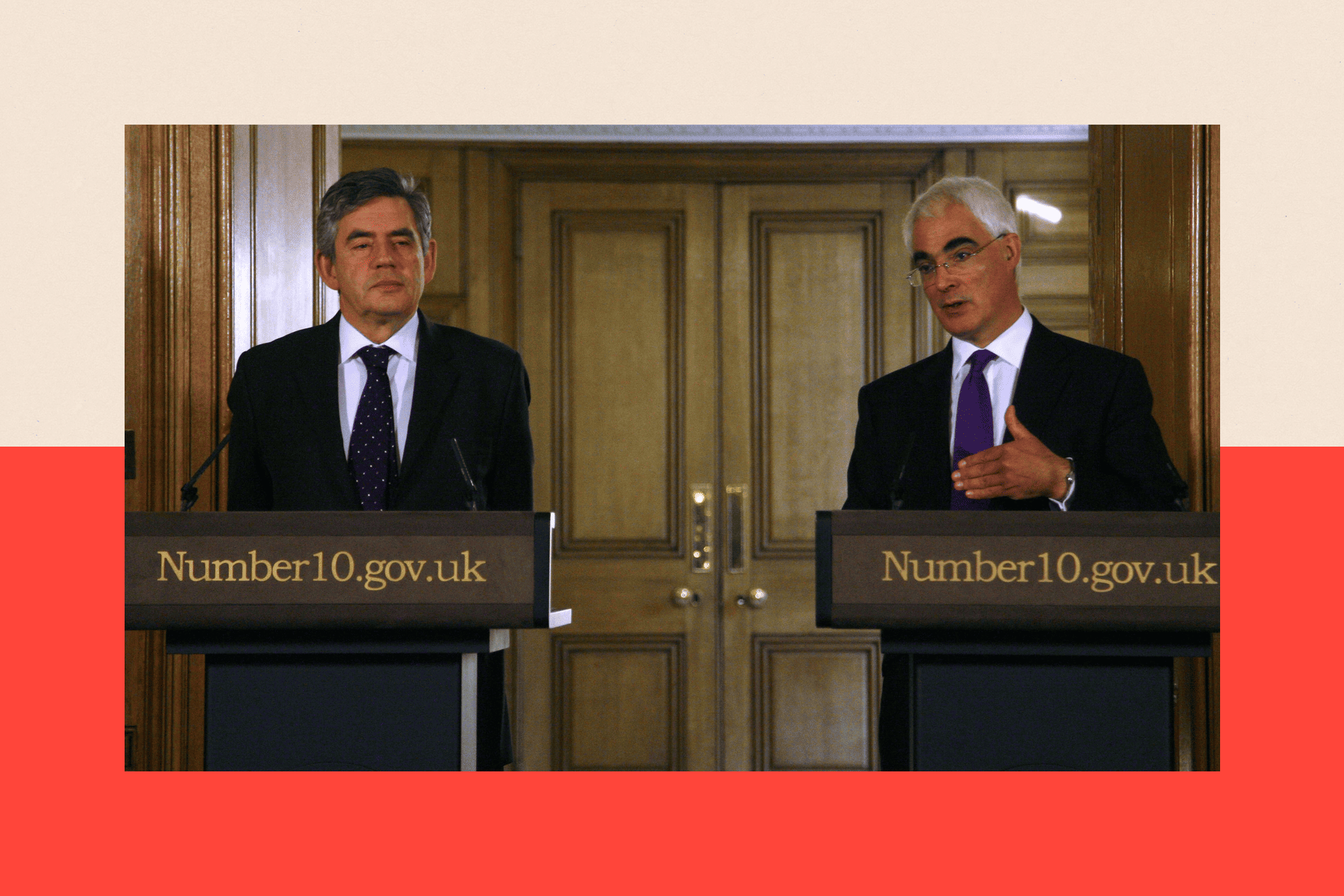

It was gone midnight – the early hours of Monday 13 October 2008 - when Chancellor Alistair Darling turned in for the night, leaving a team of officials, surrounded by curries and pizza boxes, finalising the detail of the biggest state intervention in the private sector since World War Two.

The next morning he announced the first instalment of a rescue that would cost the taxpayer more than the entire defence budget.

In total the government spent £45bn (£73bn in today's money), buying an 84% stake in the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which now trades as part of the NatWest Group.

The rescue, announced by Darling, would cost the taxpayer more than the entire defence budget

At the time, RBS's balance sheet (outstanding loans) was bigger than the entire UK economy. Its collapse would have devastated it.

The question is, why has it taken some 17 years for the Treasury to sell the last of its stake?

And given that in the decades since fresh risks have emerged - including the threat of a cyber attack from a hostile state - how vulnerable does that leave UK banks today? Are they still "too big to fail", as they were widely described in 2008 - and were Britain to face another financial crisis, would the taxpayer have to step in once again to deliver a bailout?

'It was never about saving the banks'

The current chair of NatWest group, Rick Haythornthwaite, has told the BBC that the bank and its employees remain thankful for that intervention in 2008.

"The main message to the taxpayer is one of deep gratitude," he says. "They rescued this bank. They protected the millions of businesses and home-owners and savers."

A lot has changed since 2008. Gone are £1.5 trillion in outstanding loans, gone are tens of thousands of employees in job cuts, and gone is around £10bn of taxpayers' money – never to be recouped.

The amount spent by the government looks like a poor investment, but as Baroness Shriti Vadera – former senior adviser to the government and chair of asset manager Prudential - told the BBC, this wasn't an investment, it was a rescue.

"Nationalising RBS was hardly a voluntary investment," she says. "What was important then was assessing the impact of RBS and other banks on the overall economy and in particular the ability to keep functioning – lending, putting cash in ATMs.

"It was never about saving the banks, it was about saving the economy from the banks."

The consequences of a banking collapse would have been serious. The prime minister, Gordon Brown, even talked about putting soldiers on the streets.

In a book by ex-Labour spin doctor Damian McBride, Brown is quoted as saying: "If the banks are shutting their doors, and the cash points aren't working, and people go to Tesco and their cards aren't being accepted, the whole thing will just explode.

"If you can't buy food or petrol or medicine for your kids, people will just start breaking the windows and helping themselves."

Risky mortgages and bad loans

RBS was of course not the only bank that faced collapse. A tsunami of bad loans had been triggered by an earthquake in the US mortgage market. Risky loans to borrowers with low credit ratings had been packaged up and sold to banks around the world.

By 2007, no-one knew exactly where these grenades were hidden in bank balance sheets, so they all stopped lending to each other – which saw the whole global financial system seize up.

Northern Rock relied on borrowing funds to finance its own risky mortgages and in 2007, the BBC reported that it had turned to the Bank of England for help. This prompted a "run on the bank", which finally saw it fully nationalised in February 2008.

Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, worked as the Bank's Chief Cashier during those turbulent months. He says if the state hadn't nationalised RBS, the costs would have been "incalculable".

"It would have been huge, because we were talking about the collapse of the banking system as we knew it at that time," recounts Bailey.

Andrew Bailey has been Governor of the Bank of England since 2020

US Banks were also in deep distress. In March 2008, Bear Stearns was absorbed by Wall Street rival JP Morgan. In September of that year, US mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were nationalised. Here in the UK, HBOS was absorbed by Lloyds and then of course, Lehman Brothers failed – defying expectations that the US government would step in to save it.

But for the UK economy, RBS was the big one. The UK had a large banking sector, compared to the size of its economy; and within that mix, RBS was a particularly important bank.

The once sedate RBS had become in some measure the biggest bank in the world. In 2000, it bought NatWest and just a year before the crash, it had bought Dutch bank ABN Amro.

Its buccaneering boss Fred Goodwin had been knighted for his services to banking. But Mr Goodwin became a lightning rod for public outrage at the risks banks had taken and the bonuses their executives had collected.

He left with an annual pension of £700,000 but was later stripped of his knighthood.

RBS boss Fred Goodwin became a lightning rod for public outrage during the crisis

The years following the rescue saw thousands of companies complain that the bankers RBS appointed to help them out of the crisis were driving them to the wall, forcing them into bankruptcy or selling their businesses at knock-down prices.

RBS was the poster child for banking recklessness, hubris, greed and cruelty.

Why then did it take so long for the government to sell out of RBS - at a loss of £10bn?

A mistake to hold on for so long?

At the same time the government took a stake in RBS, it also took a stake in Lloyds. But that was sold in May 2017, yielding a profit of £900m.

RBS was infinitely more complicated than Lloyds as it had a large US business which was the subject of lengthy investigations by the US Department of Justice. The prospect of heavy fines hung over the bank for many years and proved well-founded when it was fined $4.9bn (£3.6bn) in 2018 for its role in the US mortgage crisis.

RBS was also a pretty unattractive investment. It announced a £24bn loss for 2008 – the biggest loss in UK corporate history. It made losses every year until 2017.

With the shares depressed by these concerns, the government was reluctant to sell its stake at low prices as it would crystallise a politically uncomfortable loss for the taxpayer.

The Treasury announced that it will sell its final shares in NatWest Group

After all, following 2010, austerity was the name of the game and the then-Chancellor George Osborne could ill afford to be seen to be chalking up losses by selling RBS shares when he was making cuts elsewhere.

But many think that was a mistake as – chicken and egg-like – it prolonged the reluctance of private shareholders to buy stakes in a company majority-owned by the government.

As Baroness Vadera puts it: "I'm not sure it was necessary to take 17 years to reverse out of the shares."

Collapses 'less likely - but not impossible'

Mr Haythornthwaite, who took on the role of NatWest Group chairman in April last year, describes the sale of the final shares as a "symbolic" moment for the bank, its employees, investors - but also on a wider scale.

"I hope it's a symbolic moment for our nation [too]," he says. "That we can put this behind us. It allows us to truly look to the future."

But how exactly does that future look - and have lessons from the past really been learnt?

Andrew Bailey certainly thinks so. He says that if a bank faces collapse now, it's less likely the taxpayer will have to step in.

There are now alternative methods of rescuing a failing bank, he says, including buying assets and providing emergency cash.

"The big distinction is that we think we can handle [bank crises] without using public money," Bailey says. "The critical thing is that we have to preserve the continuity of their activities, because they are critical to the economy … critical to people.

"When we say we've solved 'too big to fail', to be precise, I think what we mean is we don't need public money."

It is true that the Bank of England now stress-tests banks much more rigorously to see how they would cope under pressures like a collapse in house prices, rocketing unemployment or rampant inflation.

Sir Philip Augar, a veteran of the City of London and author of multiple books on banking, agrees that British banks are in a more resilient position now than they were in 2008 - essentially because they hold more cash in their coffers, rather than just relying on debt.

"What's happened to improve things since then is that the amount of leverage in the system has come right down, and the capital cushion that banks have to hold […] has increased substantially. So it's less likely now that a bank would collapse - but it's not impossible."

Cyber risk will never go away

Today, there are also new risks to consider.

Take the series of cyber attacks that recently hit the systems of household names like Marks and Spencer, Co-op and Harrods. Should an attack take out critical banking functions like business lending, company payrolls and ATMs, it would be far more damaging.

Indeed, in what he calls the "league table" of financial risks, Andrew Bailey identifies the threat of a cyber attack as a rapidly growing one.

"Of course you have to mitigate it, but [cyber] is a risk that will never go away, because it continually evolves," he says.

"We're dealing with bad actors who will continually refine the lines of attack. And I always have to say to institutions, 'You've got to continue to work at this'."

Recent bank collapses in the US – like Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank - have highlighted another major risk. Customers don't have to queue round a block to get their money out; it can be done with the stroke of a key on a laptop or mobile in seconds.

Banks are built on trust: customers put money in, believing they can get it out again whenever they want. And a good old-fashioned bank run is now a modern digital bank run.

But banks are still not like normal companies. They are not standalone entities but interconnected, and together they form the bloodstream of the economy.

They are the arteries through which credit is extended, wages are paid, savings are stashed or withdrawn. And when those arteries get blocked, bad things happen.

That is as true today as it was in 2008.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

More from InDepth

Xi's real test is not Trump's trade war

- Published30 April

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.