'Coming-of-age' voices revealed in Stalin-era diaries

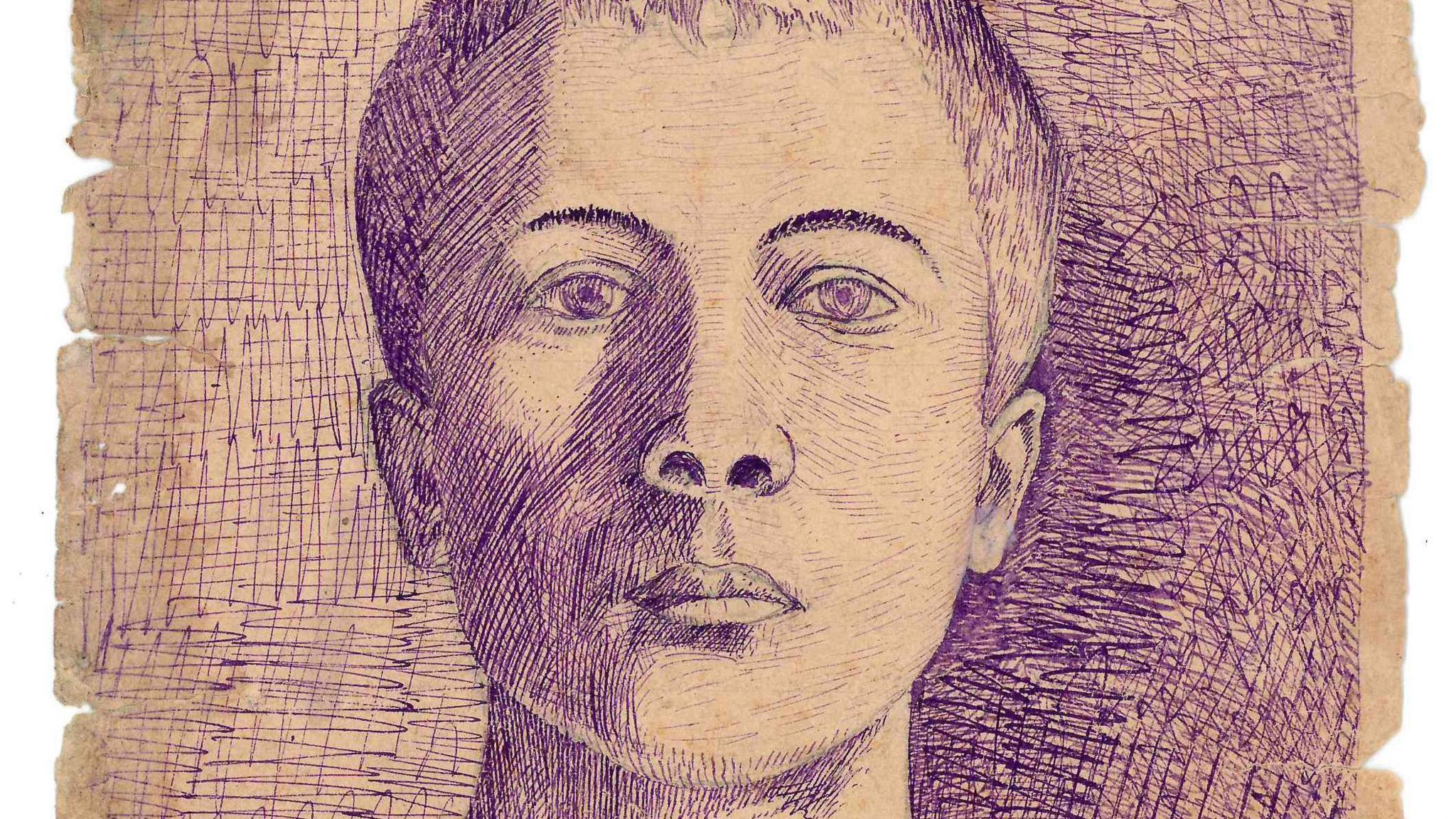

Vasilii Trushkin, 15, was a peasant who wrote poetry and aspired to be a writer. At 12, his family fled famine in the Saratov region of southwestern Russia by moving 4,800km to Irkutsk in Siberia

- Published

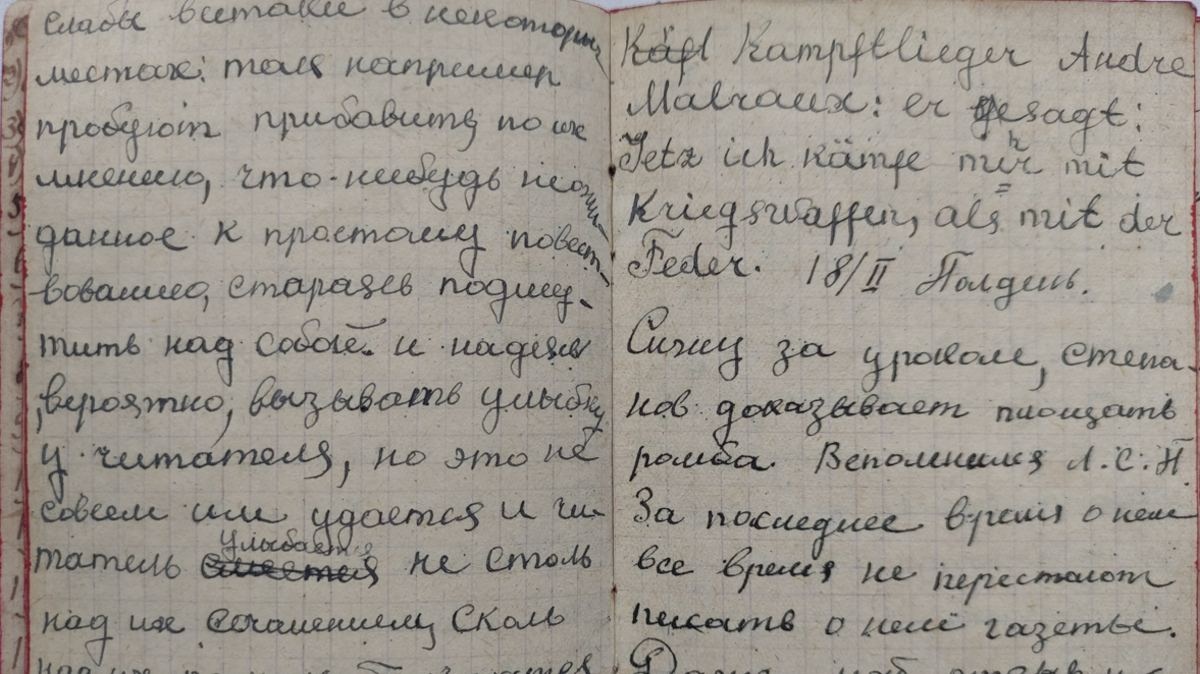

The diaries of teenage boys in pre-war Soviet Russia have revealed how they navigated ideology and propaganda while expressing themselves.

Ekaterina Zadirko, a Slavonic Studies researcher at Trinity College, Cambridge, studied 25 diaries written between 1930 and 1941.

Most of the documents had never been studied before and preserved the voices of teenage boys from a range of families and locations.

Zadirko said the diaries showed how "Soviet ideology shaped people, but they weren't completely brainwashed".

In one of Vasilii Trushkin's diary entries at 18, he wrote of being with a girl named Natasha: "It is so pleasant to feel the closeness of a beloved woman! From the sacred vessel, sung by many poets, I greedily drank pleasure. Afterwards, already in bed, I could not calm down for a long time"

The project focused on male teenagers growing up in the pre-war Stalinist era.

"Scholars tend to disregard most of what's in these diaries as just teenage concerns," Zadirko said.

"But in 1930s Russia, writing was a key strategy for teenage boys to process their coming of age and find their place in society.

"Even if their diary remained a private document, writing for these boys felt very high-stakes, even existential."

Zadirko believed the diaries provided a crucial safe space for 1930s Soviet teenagers to work out how to perform their public identity, which she said gave them an advantage over many teenagers today.

"Working out your identity in public on social media today feels much less safe... in the private setting of a diary, the only judge is yourself."

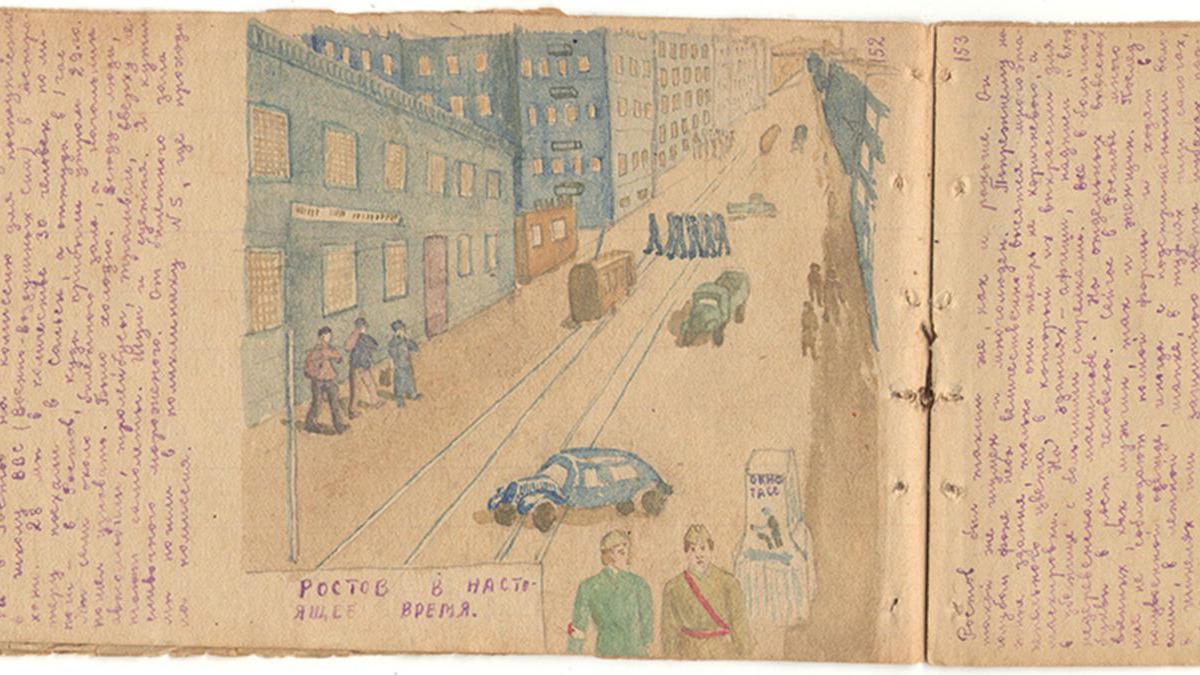

As he prepared for the military draft in 1941, Ivan Khripunov wrote: "The war makes everyone into adults. I thought I was a boy, but now I am being drafted like an adult." Less than a year later he was reported missing

One diary was that of Ivan Khripunov, the son of a man who was labelled a kulak, a wealthy peasant who was then exiled as an enemy of the people.

It was a rare example of a peasant diary written by a young person with insights into his life from 1937, at 14, until his conscription into the Red Army in 1941.

His writing followed Maxim Gorky's literary model and he wrote about his family surviving famine, exile, and his mother and elder sisters suffering from the public humiliation of 'dekulakisation'.

Ekaterina Zadirko is studying the diaries for a PhD at the University of Cambridge

"I don't think Ivan realised that he was doing something potentially dangerous," Zadirko said.

"By imitating Gorky, Ivan was following established literary conventions, but in doing so, he broke the rules of a Stalinist public autobiography, by discussing taboo subjects. It was not an expression of conscious political dissent but a clash of cultural models."

Zadirko added that from today's perspective, teenage boys in 1930s Russia seemed conforming but, while diarists used Soviet ideological concepts to fashion themselves, they did so in creative, unexpected ways.

"These boys bent and circumvented Soviet doctrine, so they retained their teenage sense of self while still trying to fit the Soviet mould," Zadirko said.

"We mustn't over exoticize Soviet lives. Soviet ideology shaped people, but they weren't completely brainwashed.

"There weren't just true believers and dissidents. People didn't simply accept or reject propaganda, or play by its rules to survive.

"The diaries show that Soviet people, including teenagers, were many things all at once, trying to assemble their identity and make sense of the world with what they were given."

Pages from Ivan Khripunov's diary showed a drawing of a street in Rostov-on-Don in 1941

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Cambridgeshire?

Follow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.