Biden burnishes his legacy with historic prisoner swap

President Biden announces prisoner swap with Russia

- Published

Last month, President Joe Biden said that he had “no higher priority” than gaining the release of Evan Gershkovich and Paul Whelan from Russian prison.

On Thursday night, after months of behind-the-scenes negotiations, arm-twisting and manoeuvring, Mr Biden and his Vice-President, Kamala Harris, exchanged hugs with the two men as they set foot at last on American soil.

For Mr Biden, it was a valedictory turn in the final months of his presidency. For Ms Harris - the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee - it was a chance to share the limelight of a foreign policy success.

In one particularly powerful moment, Mr Biden removed the American flag pin he always wears on his suit jacket lapel and put it on Mr Whelan. It was a tangible sign of the task accomplished and a promise fulfilled.

The multilateral exchange of 24 prisoners with Russia – the largest such swap since the Cold War – represents a significant feather in the cap of a man who abandoned his re-election bid less than two weeks ago.

Like many in the waning days of their White House tenures, Mr Biden has found that foreign policy is one area where a president, even when sidelined from electoral politics, can make a splash.

Typically, this focus abroad occurs at the end of a second term, when the incumbent is unburdened by a re-election campaign and domestic attention is on the party's new nominee.

Mr Biden's circumstances are unusual. The nearest historical parallel in the modern era is when President Lyndon Baines Johnson stood down his re-election bid because of growing discontent with his handling of the Vietnam War.

That war dominated Mr Johnson's final months in office – and represented his political undoing.

Mr Biden, on the other hand, has been able to take a victory lap with this prisoner swap, basking in the joy of families of the released Americans at the White House on Thursday, after more than a month of personal and political turmoil.

Unfinished business in the Middle East

Mr Biden's month of turmoil, which began with a catastrophic debate performance in late June, culminated in last week's Oval Office address to the nation, where he discussed his decision to drop his re-election campaign.

While he conceded that it was time to "pass the torch", his speech included a reminder that his presidential term wasn’t over and that his work wasn't done. It came with a heavy serving of foreign policy promises.

He said he would bring home detained Americans - which Thursday’s news significantly advanced.

He also pledged to continue to support Ukraine in its fight against Russian invaders - which recent congressional funding has guaranteed well into next year.

And he said he would work to end the war in Gaza "and bring peace and security to the Middle East".

On that last item, the news has been trending from bad to worse in recent days.

Tensions in the Middle East have been escalating dramatically. Israel was allegedly behind the assassination of a prominent Hamas political leader in Iran on Wednesday.

The chances of a conflict between Israel and Hezbollah have grown, as the two sides exchanged attacks across the Israel-Lebanon border. An Israeli strike on Tuesday killed a senior Hezbollah leader, as well as an Iranian military advisor.

The US State Department has warned American citizens to avoid travel to Lebanon – reflecting the growing concern of a widening regional conflict.

Mr Biden, who once chaired the Senate Foreign Relations committee and oversaw an international portfolio as Barack Obama's vice-president, touted his foreign policy chops as he campaigned for president in 2020.

But the Middle East has proven to be a diplomatic graveyard for even the most capable US foreign policy hands. While achieving the kind of lasting "peace and security" Mr Biden envisions would become a remarkable accomplishment, it seems as far off now as any point since the war began nearly 10 months ago.

A legacy in an election

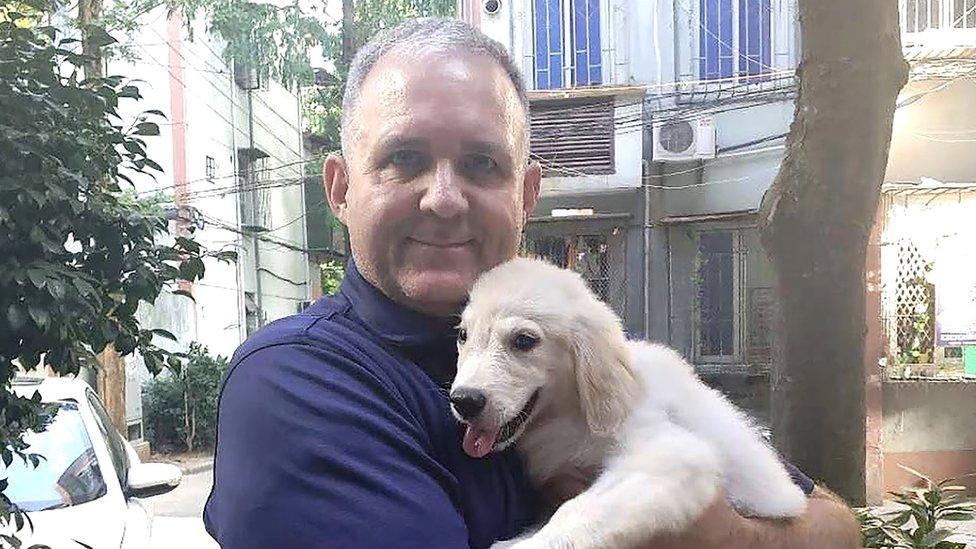

President Biden is joined by relatives of freed prisoners at the White House

While foreign policy successes could bolster Mr Biden's legacy, the president's place in the history books – and, in particular, how he is viewed by his members of his own party – hinges most directly on the fate of his chosen successor.

Although Ms Harris was not with the president at the White House on Thursday afternoon, she joined the president in greeting the newly released prisoners as they returned to US soil.

The White House also has been quick to credit the vice-president for playing a key role in negotiating details of the complex multilateral prisoner exchange with US allies.

A senior Biden administration official told the BBC that Ms Harris' February meetings with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Prime Minister Robert Golob of Slovenia at the Munich Security Conference were particularly crucial.

Meanwhile, the Republican presidential ticket has quickly attempted to minimise any political benefits from the prisoner swap – both by taking credit for it and by questioning its wisdom.

During a rally in Arizona, Republican vice-presidential nominee JD Vance said that the exchange was really a reflection of what he said was the increasing likelihood that Donald Trump would win in November.

"There's a real sense that the world leaders are afraid that if Donald Trump comes in, they’re going to have to start behaving again," he said. "The bad guys worry that Donald Trump will be back and the free ride is over.”

The former president himself posted a lengthy response on his social media website, questioning Mr Biden’s negotiating strategy and speculating about the details of the exchange.

"We never make good deals, at anything, but especially hostage swaps," he wrote. "Our 'negotiators' are always an embarrassment to us!"

The Russian asking price for the release of Mr Gershkovich and Mr Whelan - along with Russian-American radio journalist Alsu Kurmasheva and a group of Russian dissidents - was unquestionably high. It included Russian intelligence agents convicted of an assassination and espionage.

But the president and his senior staff, in their remarks on Thursday, said the deal was worth it.

Mr Biden also took a moment to tout his foreign policy vision in what could be an implied contrast with the former president's "America first", go-it-alone international outlook.

"Today is a powerful example of why it's vital to have friends in this world and friends you can trust, work with and depend upon, especially on matters of great consequence and sensitivity like this," he said. "Our alliances make our people safer."

It was a pointed message from a president whose opportunities to pull the national spotlight his way – and to burnish his legacy – are diminishing as the final days of his presidency tick away.

- Published1 August 2024

- Published1 August 2024