How social media is making young people accidental election influencers

- Published

At 15, Tolu isn’t old enough to vote in this election. But, one night from her bedroom in London, she posted a video on TikTok criticising politicians’ anti-immigration rhetoric. She woke up to find it had reached tens of thousands of people, more than many posts from the major political parties.

“The post was blowing up really quickly,” she says. “I was shocked.”

Miles away in Somerset, with political views on the other side of the spectrum, another 16-year-old, Will, was having a similar experience. He had shared clips of politicians he agrees with, highlighting concerns over knife crime and supporting Brexit, and discovered they were racking up hundreds of thousands of views.

“I find it incredibly interesting that most of the time I’m the one who is breaking news to people and not the mainstream media,” Will tells me. Unlike Tolu, who posts her views from a personal account alongside takes on music and fashion, Will has created his own logo and posts exclusively about politics.

These are just two of dozens of accidental influencers, with a range of political views, to have emerged this general election across the social media sites. Some of their amateur content is getting as much traction as the parties’ own posts - and more than some of their online ads.

Plucked from obscurity by the social media sites’ algorithms and pushed into millions of people’s feeds, the accidental influencers’ content can reach an audience who are disengaged from mainstream political commentary.

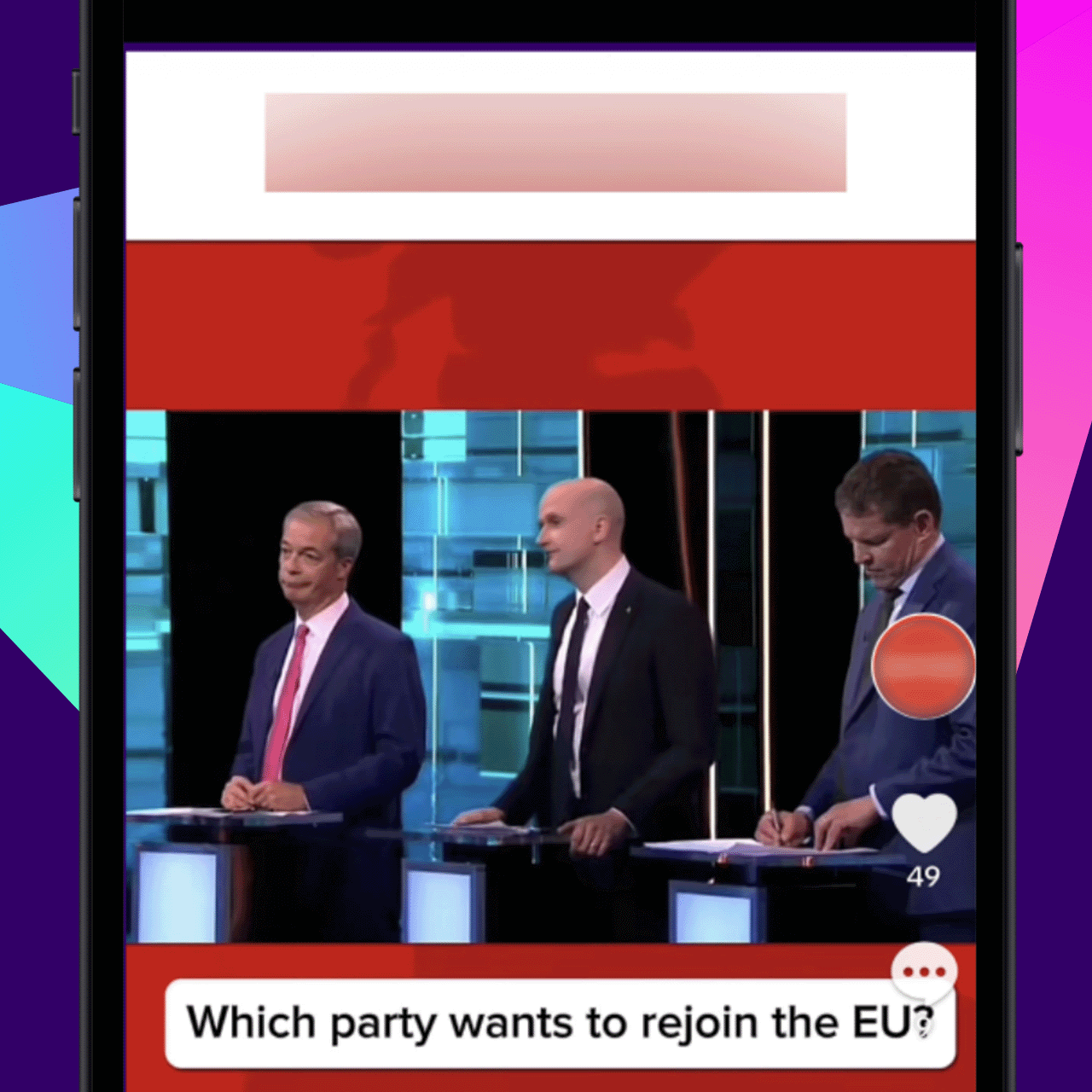

Several users I spoke to said they had been recommended content about Reform UK - such as this clip posted by Will

Their videos have appeared on the feeds of the younger characters among my Undercover Voters - 24 fictional people with private online profiles and no friends. I created them to investigate what content the algorithms are promoting during the election.

About 90% of the political posts on the feeds of the Undercover Voters aged under 35 are not from the parties themselves but from fellow social media users sharing political content.

Dozens of the accidental influencers I have identified - aged between 16 and 31 - have received on average about half a million views for each of their posts. Several have had close to a million views on individual videos - and collectively they have racked up more than 15 million.

Giving young people a platform can encourage them to voice their opinions and take part in the democratic process - and lots of these profiles are sharing reliable updates and hot takes. But with great virality comes great responsibility - some other accounts like this have shared misleading claims, as well as finding themselves a target for threats and abuse.

Some other viral accounts have shared misinformation, like this faked image of Sir Keir Starmer in a Palesintian flag T-shirt

Several of the influencers say they have been told their posts have changed other people’s minds about whether to vote and who for. Some say they have felt encouraged to post the content they know will rack up the most likes, regardless of whether they believe in it. One even says she has been in contact with a political party about her content.

Alex, 20, from West Yorkshire says he was encouraged to start posting election content after more UK political posts were pushed to his own feed.

His social media feeds used to recommend videos about football, as well as influencer Andrew Tate - who is facing a trial in Romania over rape and trafficking charges. There was some political content in between too, he says, about former US President Donald Trump and some European right-wing politicians.

But more recently, the political content has become dominated by posts about Reform UK, usually on the subject of immigration or opposing “wokeism”, he says.

Reform UK content has also been recommended to other users who have very different interests to Alex.

After Nigel Farage became leader of Reform UK, Alex says he was inspired to make political content on the same topics he had seen on his feed. “I have always liked him,” he says.

Within days his posts were reaching tens of thousands of views - equal to many of those from official party accounts.

Marianna Spring: Why am I tracking 24 phones this election?

What happened to Alex, Tolu and Will is symptomatic of how social media sites have changed since the last general election. TikTok, Instagram and X all work by recommending content to users’ “For You” pages or feeds - often from people they don’t follow or know, allowing individuals to go viral instantly, without building up a big following first.

This evolution means that paid political advertising on some social media sites, like Facebook or Instagram, is getting less attention than the content created by individual users and then promoted by the social media algorithms - including on apps like TikTok, where paid-for political ads are not allowed.

Several of the social media users whose political content has gone unexpectedly viral also did not anticipate the hate, trolling and threats which followed. Tolu says she received racist abuse with graphic descriptions about slavery, while Alex says he has received messages threatening to release his home address and details about his family in response to his posts.

The BBC is not using the online usernames of the people featured in this story to protect them from the risk of further abuse.

While Alex was already sympathetic to Reform UK before its content was pushed into his feed, I spoke to several other users in their 20s - such as 28-year-old Pete who lives in West Yorkshire - who had shown no interest in Reform UK previously, but whose feeds had also become dominated by political content featuring Reform UK talking about immigration.

I found the same on my fictional Undercover Voters’ feeds.

Pete says his feed has been dominated by Reform UK content, although he went viral with a post urging voters to consider the Green Party

Thomas, 30, from Lancashire, told me he had responded to the prominence of Reform UK content by uploading “a fair amount of old clips of Farage speaking in the EU, as it attracts views” even though they do not reflect his own opinions.

While we know some reasons why certain content is likely to be promoted - such as whether it is on a topic already generating a lot of engagement - we don’t know exactly why and how social media algorithms choose what to push.

On the accounts of my Undercover Voters, I have noticed the political content popping up does not always reflect trends in recent polling, which indicate young people leaning heavily towards Labour. As well as support for Reform UK, the feeds feature criticism of Labour from a left-wing perspective and also backing for the Green Party.

These viral posts were pushed to our young Undercover Voter profiles in six battleground constituencies

While most of these accidental influencer profiles I have spotted have no political affiliations, 21-year-old Kate who runs a left-leaning political account does tell me she has been in contact with the Labour Party about her profile. But she says she is not paid and the party has no control over what she posts.

This is the first general election she can vote in, but she has been posting about politics for several years. She says she has racked up 2.1 million likes and more than 18 million views - more than most of the parties’ official TikToks.

“In the past, I’ve had people comment they didn’t know something I’ve included and now they wouldn’t vote Tory,” she tells me.

The ability to influence other voters, though, comes with risk. Unlike media outlets, which are subject to regulation, there is little oversight of these posts which can reach millions of people.

Posts from the real accidental influencers were spotted on the feeds of our seven fictional Undercover Voter profiles aged under 35

Some of the other profiles which have gone unexpectedly viral have shared misleading posts mixed in with reliable updates and opinions.

One posted a doctored image falsely suggesting Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer wore a white T-shirt with the Palestinian flag to watch an England match in Euro 2024, calling him a traitor and provoking abusive comments.

Another shared a conspiracy theory falsely suggesting that a milkshake thrown at Nigel Farage while he was out campaigning had actually been staged by his own political party.

Other accidental influencer profiles have used graphics of real polls to make misleading predictions about the election outcome - and some have posted incorrect claims about the positions of different political parties on issues such as immigration and Brexit.

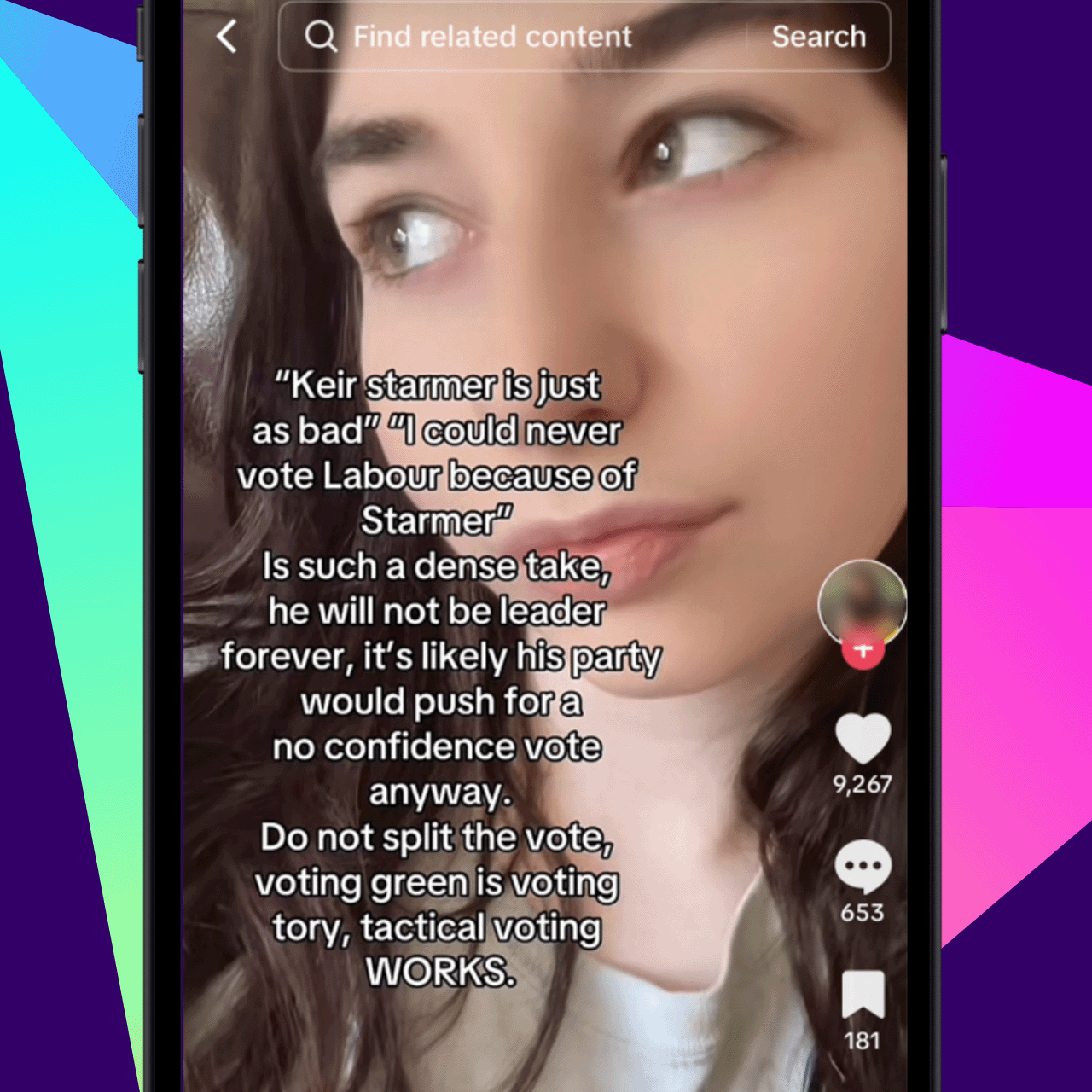

Georgina, 18, a student in Edinburgh, says it was “quite overwhelming” when her post urging young people to vote Labour, not Green, and giving her opinion that Sir Keir could be replaced as leader after the election, racked up 100,000 views. She thinks many people - like her - are not prepared for going viral during an election campaign.

“If you post with the idea that your post could be seen by millions, then you’d probably be a lot more careful about what you’re saying,” she says.

“I was concerned that maybe I didn’t provide enough context and official information.”

Georgina said she wished she had added more context to her post suggesting Sir Keir Starmer could be replaced as Labour leader

Some of these accidental influencers tell me they are putting lots of effort into researching their own posts and ensuring they are accurate. Several also say, though, that they are finding it hard to work out what to share, because they are unsure what to trust on their own feeds.

They say opinions can sound like facts and several tell me they have seen a lot of AI-generated content about the election - predominantly parody clips.

That includes faked satirical clips that purport to show Sir Keir Starmer, Rishi Sunak and Nigel Farage “live streaming” the video game Minecraft. Other altered images the influencers have come across include a faked image of Rishi Sunak at a Morrisons supermarket made to look like the sign behind him reads “moron”, with his head obscuring part of the brand name.

Several people told me that while some of these fakes are obvious, there are others that “blur the line between fact and fiction”.

Parody videos of leaders such as Rishi Sunak live-streaming Minecraft were among the AI fakes seen by these influencers

According to a TikTok spokesperson, it has increased its investment “in efforts to ensure reliable information can be found on TikTok”, launching a “UK Election Centre with a fact-checking expert” and adopting an “industry-leading AI labelling technology”. It said also does not allow misinformation about the election or bullying and harassment.

An X spokesperson previously told the BBC: “X has in place a range of policies and features to protect the conversation surrounding elections.”

A spokesperson for Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, has said they have a “UK-specific Elections Operations Centre” to identify threats and misinformation.

Following my earlier investigations into misinformation promoted to voters, and deepfaked clips used to smear politicians, sites have also taken action by removing accounts and content.