Heathrow warned by airlines about power supply days before shutdown

- Published

Heathrow Airport was warned about the "resilience" of its power supply in the days before a fire which shut down the airport for more than a day last month.

Nigel Wicking, chief executive of Heathrow Airline Operators' Committee, a group representing airlines, told MPs on Wednesday that he spoke to Heathrow twice in the week before the closure on 21 March.

He questioned why the airport was closed as long as it was and why it was not more prepared considering its importance.

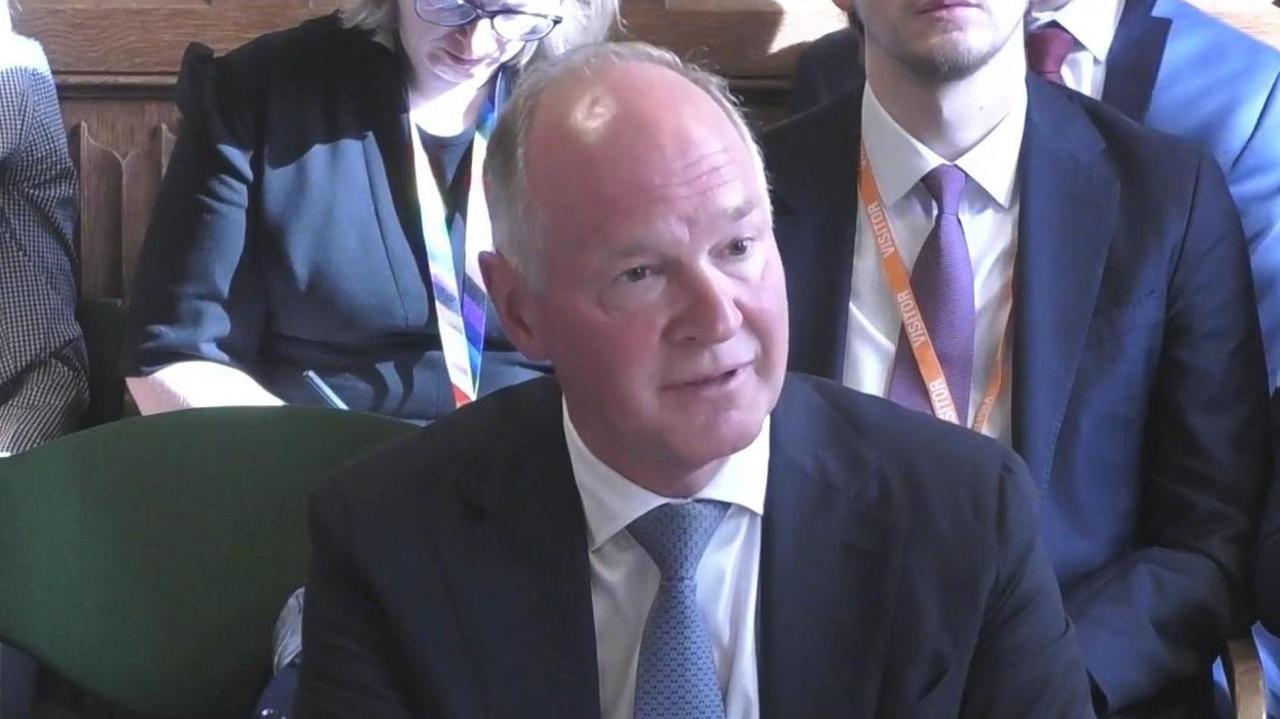

However, Heathrow boss Thomas Woldbye called the fire an "unlikely event" and defended the length of the closure, saying he had to make "very serious safety decisions".

Mr Woldbye apologised to the more than 300,000 passengers whose journeys were disrupted.

He offered his "deepest regrets" adding that the "situation was unprecedented". The airport was shutdown after a fire at an electrical substation.

The chaos at Heathrow has raised concerns about the reliability of the major transport hub - and brought into question the UK's energy resilience more broadly.

Power concerns

Speaking to MPs on the transport committee, Mr Wicking said he raised cases of "theft of wire and cable around some of the power supply" which he said temporarily took out runway lights, which are critical to passenger safety.

"I wanted to understand better the overall resilience of the airport."

He said he had spoken to the Team Heathrow director on 15 March about his concerns - six days before the fire - and the chief operating officer and chief customer officer on 19 March - two days before the fire.

Mr Woldbye said the airport had to rely on contracts it has with Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks for making the network resilient, and to improve that "comes at a very high cost", which would raise costs for airlines, and passengers.

However, Mr Wicking said Heathrow is "already the most expensive airport in the world".

"From an airline perspective, we expect resilience, we expect there to be the capability there and the understanding of when a power supply or an asset is not available, what will you do next, and how quickly will you bring it back?"

On the day of the shutdown, airlines had to divert 120 aircraft, which is "not a light decision to be made in any context", Mr Wicking added.

As a consequence, when Mr Wicking joined a call with NATs, the national air traffic service, at 05:30, "they'd run out of space within the UK for aircraft to divert".

"Aircraft were then going to Europe, and then some were even halfway across Europe and going back to base in India," he said. "So, quite a level of disruption for those passengers, let alone all of the cancellations".

There were 1,300 cancelled flights, he said.

The airport reopened on the Saturday following the fire.

When asked why it had not reopened sooner, Mr Woldbye said that could have meant passengers got hurt.

He said: "If we had got this wrong, we might be sitting here today having a very different discussion about why people got injured, and I think it would have been a much more serious discussion.

"So there is a margin within which our people have to take very serious safety decisions, and that is what they are trained for, that is what they do, and that requires that every single system is up and running, tested and safe."

However, Mr Wicking said Terminal 5 could have reopened sooner.

He said: "In terms of T5, my understanding both from British Airways but also on the day, was that pretty much everything was fine to operate by mid-morning, by 10 o'clock."

'Losing power'

After the substation fire began on the Thursday night, Mr Woldbye said Heathrow realised "during the early hours" of Friday 21 March that "we were losing power to the airport".

"In our operations centre you would seen all the red lights go, that the systems were powering down," he said. "We had no information as to why."

"We then had a slightly later stage call from the fire department that the substation was on fire," he said.

Heathrow is supplied by three substations, but knocking out one caused the airport to shut down.

Mr Woldbye said a third of the airport was powering down and that Terminal 2 was particularly affected, along with certain central systems. He added that it became "first and foremost a safety situation".

"We need to make sure, when a crisis happens, that people are safe," he said.

The safest way to proceed was to shut down airport systems, then bring them back on line, he said.

The first priority was to check that no-one been caught in lifts or was hurt.

Safety critical systems such as runway lighting and the control tower "switched in as they should", however, he said.

The government has backed plans for Heathrow to build a third runway as part of efforts to boost UK economic growth.

The airport would need double the amount of power for its expansion plans, Mr Woldbye said.

However, Mr Wicking said airlines, which support expansion, nevertheless had concerns that it would cost £40bn to £60bn, and that the costs would ultimately be passed onto passengers in the form of higher fees.

The danger was the expansion could turn into a "white elephant", he said.