'You are under digital arrest': Inside a scam looting millions from Indians

Ruchika Tandon had nonstop surveillance by strangers on the phone

- Published

For a harrowing week in August, Ruchika Tandon, a 44-year-old neurologist at one of India’s top hospitals, was ensnared in what felt like a high-stakes federal crime investigation.

Yet, it was an elaborate scam - a web of deceit spun by scammers who manipulated her every move and drained her and her family’s life savings.

Under the pretence of “digital arrest”- a term fabricated by her perpetrators - Dr Tandon was coerced to take leave from work, surrender her daily freedoms, and comply with nonstop surveillance and instructions from strangers on the phone, who convinced her she was at the centre of a grave investigation.

The “digital arrest” scam involves fraudsters impersonating law enforcement officials on video calls, threatening victims with arrest over fake charges, and pressuring them to transfer large sums of money.

In Dr Tandon's case, they stripped her and her family of nearly 25m rupees ($300,000; £235,000) across bank accounts, mutual funds, pension funds, and life insurance - years of savings lost in a manufactured nightmare.

She is not alone. Indians lost over 1,200m rupees to “digital arrest” hoaxes between January and April this year, according to official figures. These figures only scratch the surface, as many victims don’t report such crimes. Stolen funds are often funnelled into overseas accounts or cryptocurrency wallets. More than 40% of the scams have been traced back to Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, according to officials.

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay was kept 'hostage' in his study and forced to sleep on the couch by the scammers

Things are so bad that even Prime Minister Narendra Modi talked about the scam, external in his monthly radio talk in October.

"Whenever you receive such a call, don’t be scared. You should be aware that no investigative agency ever inquires like this through a phone call or a video call," he said.

India faces a range of cyber crimes, from fake investment and trading to dating scams. But the “digital arrest” scam stands out as especially elaborate and sinister - meticulously planned, relentless, and invasive to every part of a victim's life.

Sometimes scammers reveal themselves during video calls, while other times they remain hidden, relying solely on audio. The plot could be straight out of an outlandish Bollywood thriller - except it is carefully choreographed.

On that fateful first day, scammers posing as officials from India’s telecom regulator called Lucknow-based Dr Tandon, claiming her number would be disconnected due to “22 complaints” of harassing messages sent from it.

Moments later, a man claiming to be a senior police officer took over. He accused her of using a joint bank account with her mother to launder money for women and child trafficking.

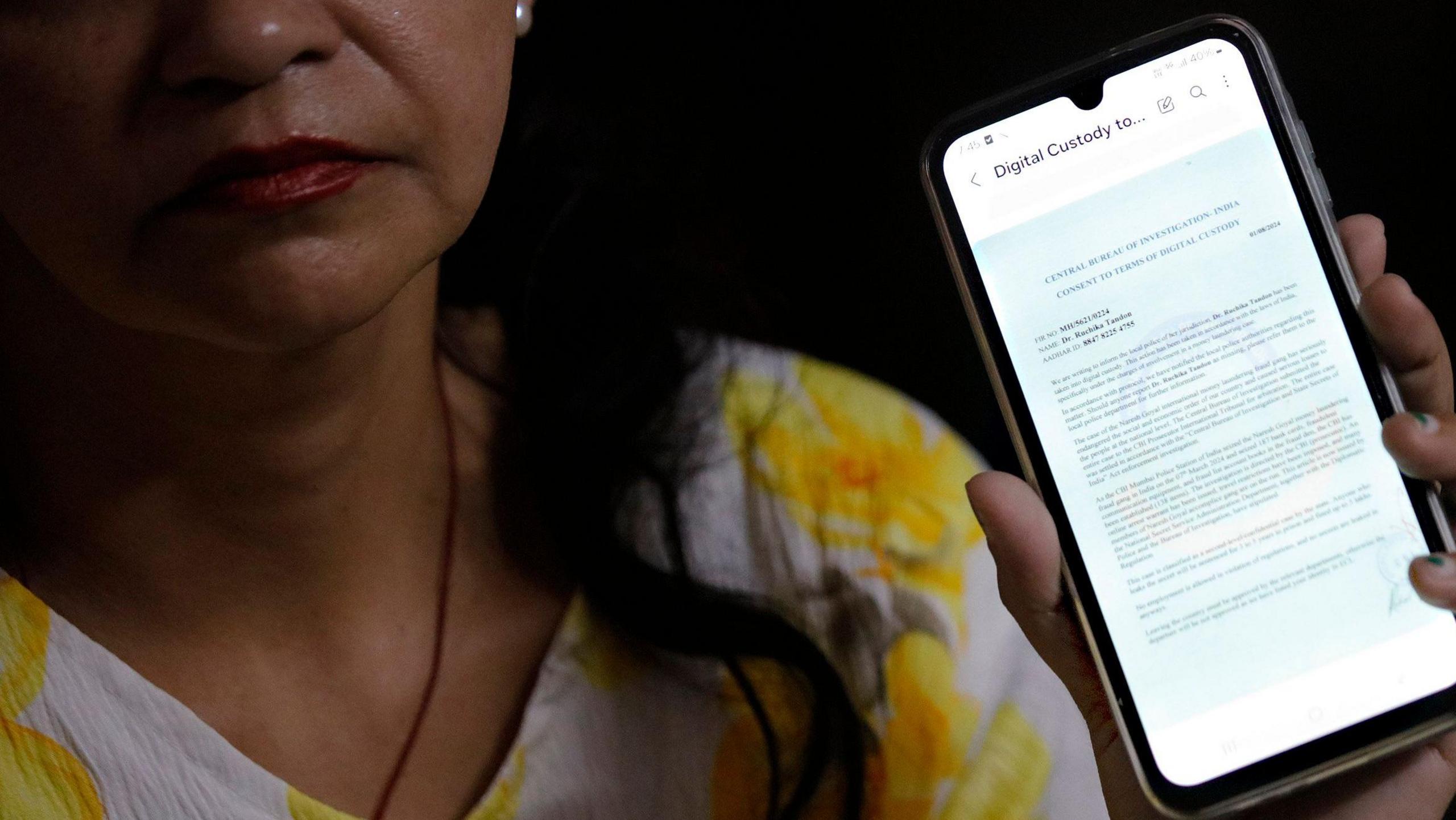

Dr Tandon received a fake 'consent to terms of digital custody'

In the background, a jarring chorus of voices echoed, “Arrest her, arrest her!”

“The police will be coming in five minutes to arrest you. All police stations have been alerted,” the man warned.

“I was angry and frustrated. I kept saying this can’t be true,” Dr Tandon recalls.

The officer seemed to soften, but with a catch. He said India’s federal detective agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), would take over as it was a “matter of national secrecy".

“I will try to talk and persuade them not to put you in physical custody. But you have to be in digital custody,” he insisted.

Dr Tandon used a feature phone that lacked video calling, making it impossible for the scammers to proceed. So they forced her to drive to a store and buy a smartphone.

Over the next six days, three men and a woman, posing as police officers and a judge, kept her under constant surveillance on Skype, with her phone camera running nonstop.

They made her wake up her students at night to buy extra data packs to keep the scam going. She was required to place the phone throughout the house - while cooking, sleeping, and even outside the bathroom - tracking her every move.

Mr Mukhopadhyay's desktop screen showed only the fake badge and name of the 'police official'

She was also forced to lie to her hospital and relatives, claiming she was too ill to work or meet anyone. When an uncle visited, they ordered her to hide under a bed, with the phone camera running.

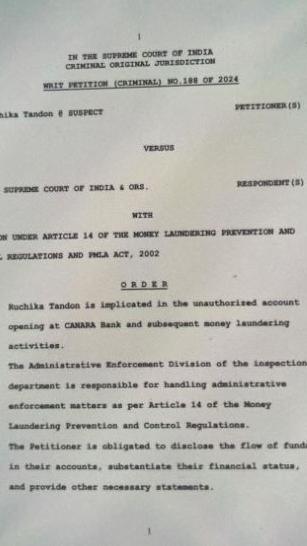

For a full week, Dr Tandon endured more 700 questions on her life and work, a staged trial, falsified court documents, and promises of a digital “bail” in exchange for her life savings. In the fake court she was ordered to dress in white to “show respect to the judge". The callers had switched off their video, leaving only their fake names and authentic-looking badges displayed on blank screens.

At one point, during the ordeal, the scammers even talked to Dr Tandon’s 70-year-old mother, urging her to stay silent "for her daughter’s sake".

When the doctor repeatedly broke down on camera, the scammers told her: “Take a deep breath and relax. You have not committed a murder. You have just laundered money."

In a desperate bid for freedom, she transferred her entire savings from half-a-dozen different bank accounts to accounts controlled by the scammers, believing she would be refunded after “government verification". Instead, she lost everything. The callers disconnected the line after transfer was completed.

Dr Tandon was surveilled 24/7 for a week - even when she was cooking

Back at work after a week, exhaustion drove Dr Tandon to search terms like “digital custody” and “new CBI investigation methods” on the internet.

This led to newspaper stories detailing similar “digital arrest” scams across the country. She still had refused to accept she was a victim of an elaborate hoax, and had rushed to the police station, hoping that “the police station and officers were real”.

Dr Tandon says she approached the police station, anxious.

"I've been receiving strange calls for days," she started, trying to explain.

Before she could say more, a woman officer interrupted sharply, "Have you transferred any money?"

At another police station, "the moment they heard my case, they began laughing", Dr Tandon recalls.

"This is very common now,” a policeman said.

Mr Mukhopadhyay says he was a 'digital slave' trapped in his study

Over 500km (310 miles) away in Delhi, author and journalist Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay narrowly escaped the scam in July.

He endured 28 hours under "digital arrest," as scammers claimed that his defunct bank account had been used to launder money. Mr Mukhopadhyay’s suspicions aroused when a caller asked him why he hadn't redeemed his mutual funds - not a question a police officer would usually ask on the phone.

Mr Mukhopadhyay slipped from his study, where scammers were surveilling him on his desktop, and confided briefly with his wife. Friends, alerted by his message, quickly asked her to disconnect his modem, freeing him from their grip.

"I became a digital slave until my friends exposed the scam," says Mr Mukhopadhyay. "I had moved my funds into my account, ready to transfer it all to them. I felt like a fool when it was over.”

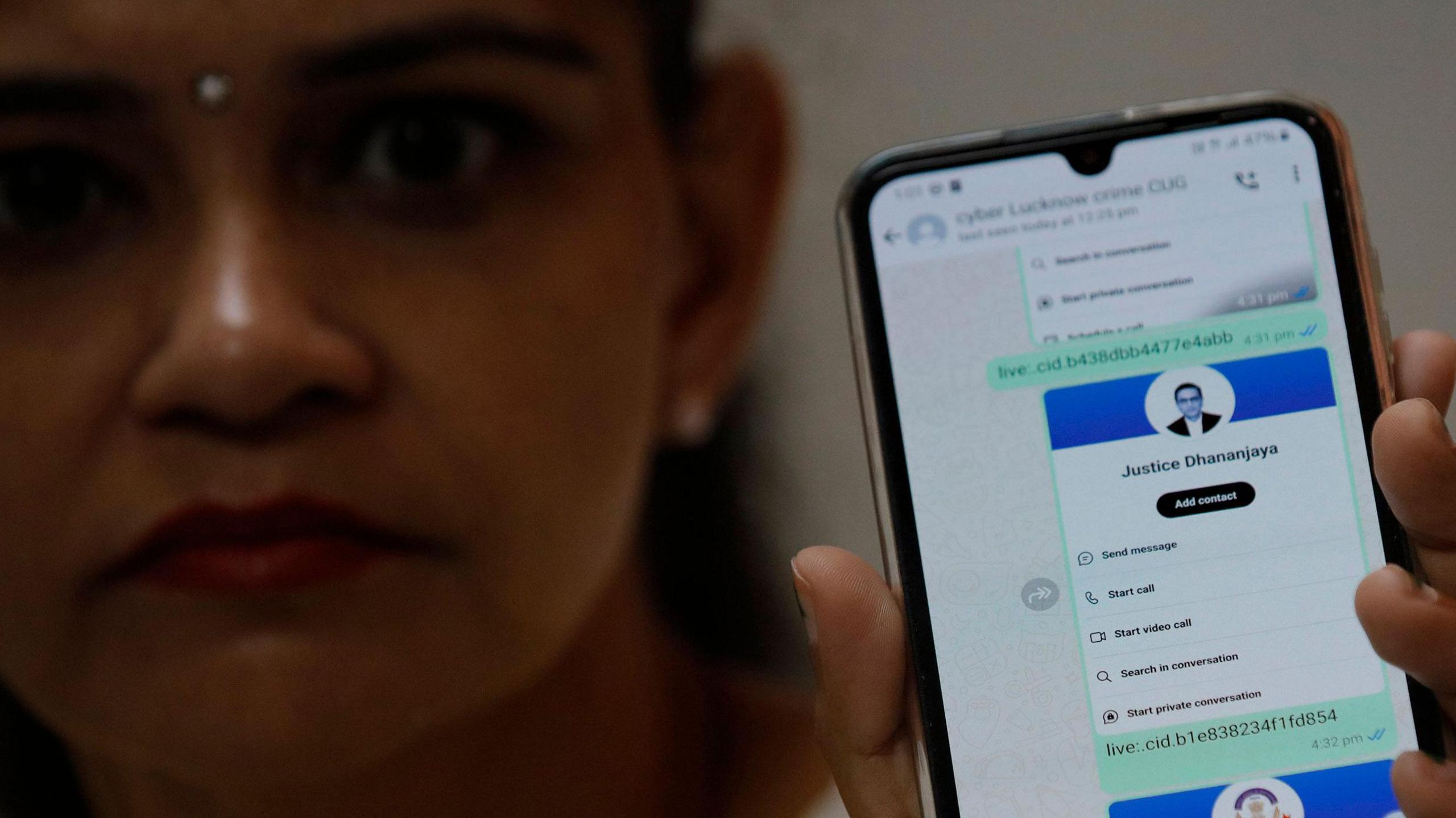

The fake "Judge Dhananjay" displayed an insignia featuring a photo of retired Chief Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud

Progress on catching these scammers remains unclear, with many victims frustrated by slow moving complaint processes.

Dr Tandon, however, has seen some success: police have arrested 18 suspects, including a woman, from across India. About a third of the stolen money has been recovered in cash and seized in different bank accounts. She has received only 1.2m of the 25m rupees of her looted money so far – that was the cash recovered.

Investigating officer Deepak Kumar Singh says the scammers were running an elaborate operation.

"The scammers are educated men and women - fluent in English and various Indian languages - including engineering graduates, cyber security experts, and banking professionals. Most operate through Telegram channels," Mr Singh, a senior police official, told the BBC.

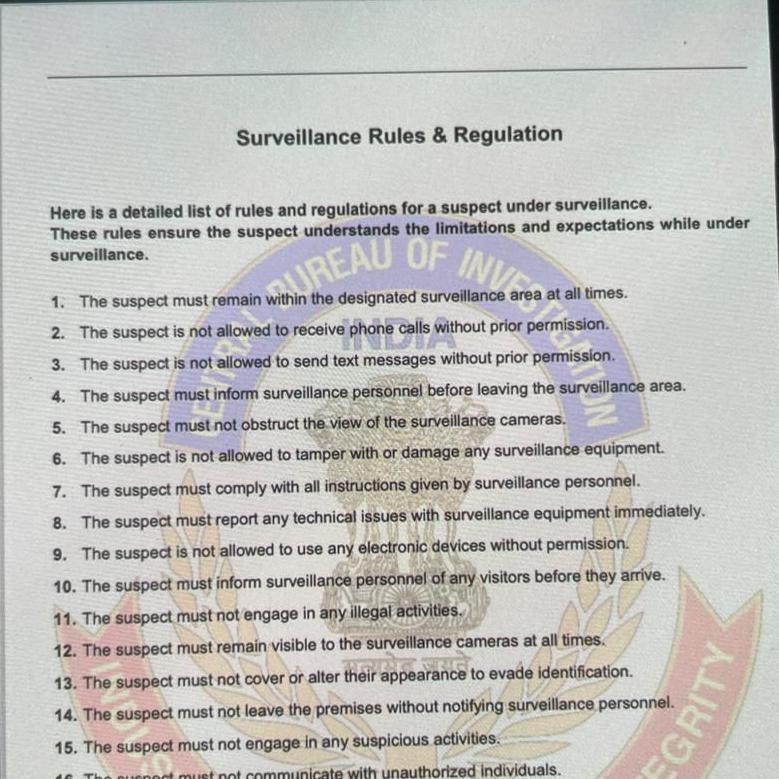

Victims of the scam are sent fabricated surveillance 'rules' from India's top investigation agency

...and a fake Supreme Court judge decides on the 'case'

The scammers were clever, using targeted information from their victims' social media, investigators believe.

"They track you, gather personal information, and identify your weaknesses," says Mr Singh. "Then they strike quickly, using a hit-and-run approach with potential victims."

The scammers knew Mr Mukhopadhyay was a journalist and writer - author of a biography on Prime Minister Modi. They knew Dr Tandon was a doctor and had attended a conference in Goa. They had their biometric national identity numbers. Mr Mukhopadhyay wonders if they were aware he was among the journalists whose house was raided by Delhi police in October 2023 as part of an investigation into the funding of NewsClick (Critics had deplored the move as an attack on press freedom, a charge the government denied.)

They also made errors. Mr Mukhopadhyay’s caller was unaware of how long it typically took to redeem funds, which raised his suspicions. Dr Tandon’s fake judge, called himself Judge Dhananjay and displayed a fake insignia with a picture of the recently retired Chief Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud. Yet, overwhelmed by the moment, she missed the clue.

Dr Tandon says she still lives in a haze, struggling to separate reality from the nightmare that overtook her life. Even when she filed the police complaint, she wondered, “Was the police station also fake?”

Every phone call stirs fresh anxiety.

“At work, I sometimes go blank, filled with fears. Days are better, but after dusk, it becomes hard. I get nightmares.”

Related topics

Read more stories from India

- Published1 April 2024

- Published27 October 2024

- Published22 October 2024

- Published11 July 2024