'My skin was peeling' - the African women tricked into making Russian drones

- Published

On her first day of work, Adau realised she had made a big mistake.

"We got our uniforms, not even knowing exactly what we were going to do. From the first day of work we were taken to the drones factory. We stepped in and we saw drones everywhere and people working. Then they took us to our different work stations."

Twenty-three-years-old and originally from South Sudan, Adau says last year she was lured to the Alabuga Special Economic Zone in the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia, on the promise of a full-time job.

She had applied to the Alabuga Start programme, a recruitment scheme targeting 18-to-22-year-old women, mostly from Africa but also increasingly from Latin America and South-East Asia. It promises participants professional training in areas including logistics, catering and hospitality.

But the programme has been accused of using deception in its recruitment practices, and of making its young recruits work in dangerous conditions for less pay than advertised. It denies all these allegations but did not deny that some employees were helping to build drones.

The Alabuga Start programme (AS) recently made global headlines when South African influencers advertising the programme were accused of promoting human trafficking. The BBC reached out to the implicated influencers and the promoter responsible for connecting them to the programme but none responded to our requests.

By some estimates more than 1,000 women have been recruited from across Africa, external to work in Alabuga's weapons factories. In August the South African government launched an investigation and warned its citizens not to sign up.

Adau has asked the BBC not to use her surname or picture as she does not want to be associated with the programme. She says she first heard about it in 2023.

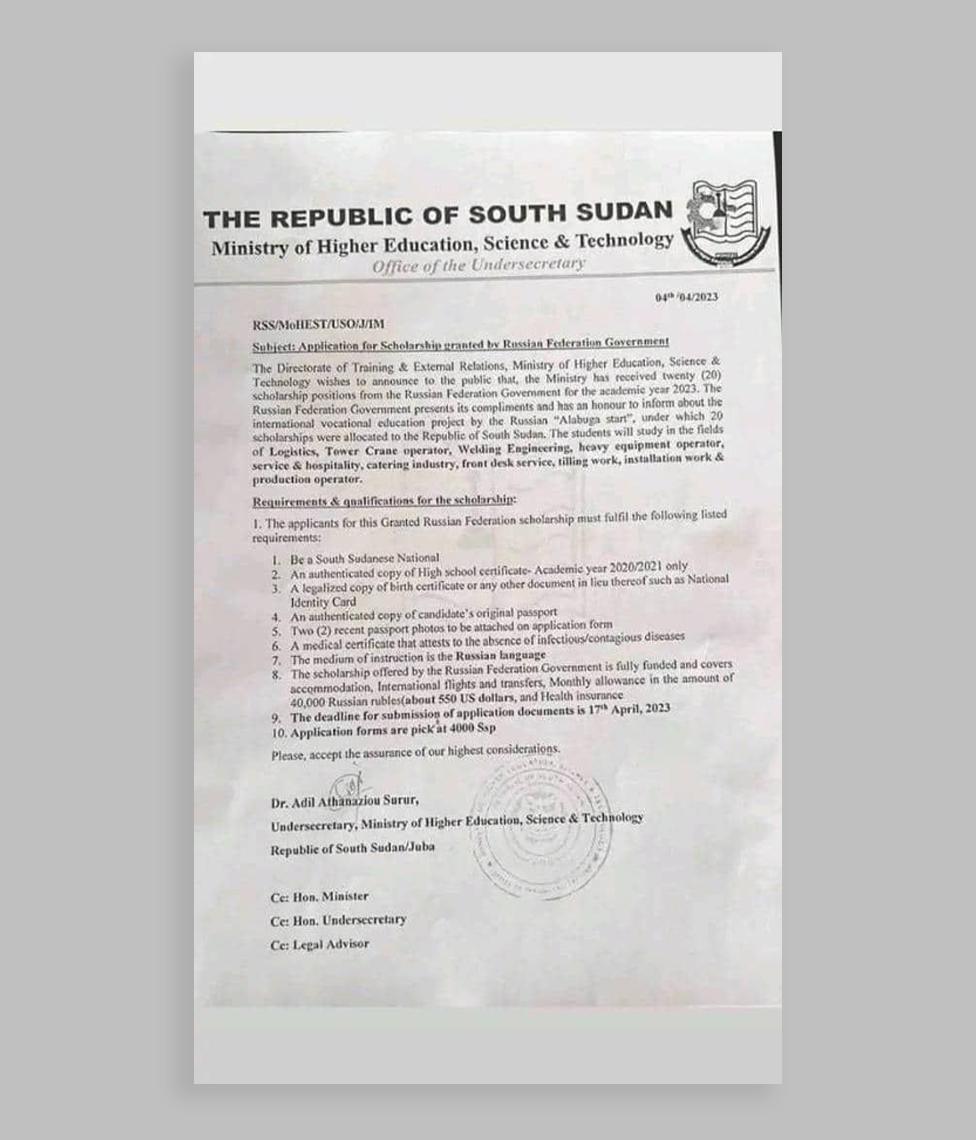

"My friend posted about a scholarship in Russia on their Facebook status. The advert was by the South Sudanese Ministry of Higher Education," she says.

Adau signed up after seeing this official advert sponsored by Russia

She reached out to the organisers through WhatsApp.

"They asked me to fill out a form with my name, age and why I wanted to join Alabuga. And then they also asked me to pick three fields I wanted to work in."

Adau says she picked being a tower-crane operator as her first choice. She had always been into technology and had even travelled abroad once to take part in a robotics competition.

"I wanted to work in fields that are not normally done by women. It is very hard for a woman to come across fields like tower-crane operation, especially within my country."

The application took a year because of the lengthy visa process.

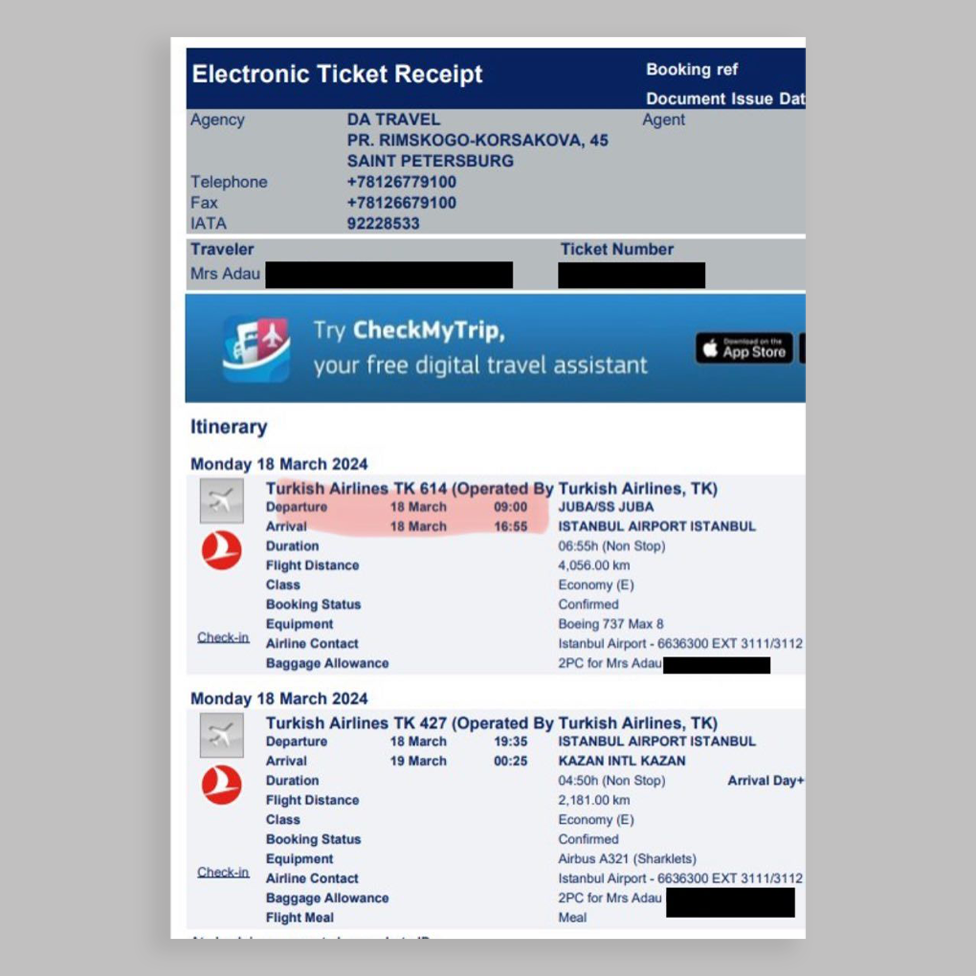

Adau's ticket to Tartastan

In March last year, she finally made it to Russia.

"When I first got there it was very cold, I hated it. We travelled towards the end of winter. The second we stepped out of the airport, it was freezing cold."

But driving into the Alabuga Special Zone left her with a good first impression.

"I was very impressed. It was everything that I thought it was [going to be]. I saw a lot of factories, cars and agricultural companies."

Adau had three months of language classes before starting work in July. That was when things started to go downhill.

She says she and the other participants were not given a choice as to whether to work in the drone factory. They had signed non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) so could not even discuss their work with their families.

"We all had a lot of questions. We had all signed up to work in technical fields -production operation, logistics, tower-crane operator - but we all ended up working in the drone factory."

Alabuga denies using deception to recruit workers. "All the fields in which our participants work are listed on our website," it said in response to our questions.

The workers were not allowed to take pictures inside the facility, but the BBC showed Adau footage broadcast on Russian state-owned TV station RT of a factory in Alabuga making Iranian Shahed 136 drones. She confirmed to us that this was where she worked.

"The reality of the Alabuga Special Economic Zone is that it's a war production facility," says Spencer Faragasso from the Institute For Science And International Security.

"Russia has openly admitted that they are producing and building Shahed 136 drones there in videos that they released publicly. They boast about the site. They boast about its accomplishments."

Spencer says that like Adau, many of the women they interviewed who worked in the programme said they had no idea they would be building weapons.

"On the surface, this is an amazing opportunity for many of these women to see the world, to gain work experience and to earn a living wage. But, in reality, when they're brought to Alabuga, they have a harsh awakening that these promises are not kept, and the reality of their work is far different from what they're promised."

Adau says she knew straight away that she could not keep working at the factory.

"It all started clicking: all the lies that we have been told since the time of application. I felt like I couldn't work around people who are lying to me about those things. And I wanted to do more with my life than work in a drone factory."

She handed in her notice but was told the notice period was two weeks, during which she had to work. During that time she painted the outer casing of the drones with chemicals she said burned her skin.

"When I got home I checked my skin and it was peeling. We wore protective gear, white cloth overalls, but the chemicals would still pass through them. They would make the fabric stiff."

Alabuga says that all staff are provided with the necessary protective clothing.

The chemicals burns on the arm of Adau's colleague

And that was not the only danger. On 2 April 2024, just two weeks after Adau arrived in Russia, the Alabuga Special Economic Zone was targeted by a Ukrainian drone strike.

"That day I woke up to our fire alarm, but this one was unusual. The windows on the upper floor of our hostel were shattered, and some of the girls had woken up to an explosion. So we went outside."

As they started walking away from their hostel in the cold morning air, Adau said she noticed others starting to run.

"I see some people pointing up, so I look up to the sky, and I see a drone coming through the sky. That's when I started running as well. I ran so fast I left the people who ran before me behind."

The BBC verified footage that Adau sent us from the day of the attack and confirmed it was taken on the same day and location of the deepest Ukrainian drone strike into Russian territory at the time.

Photos taken by Adau on the day of the Ukrainian drone strike

"The drone struck down the hostel right next to ours. It completely shattered that building and our building was also damaged."

Months later, when she found out she had been working in a drone factory, she thought back to the attack and realised that was why they had been targeted.

"Ukraine knew that the African girls who had come to work in the drone factories, lived in that hostel that was struck down. It was in the news. When Ukraine was accused of hitting civilian houses, they said: 'No, those are workers working in drone factories.'"

A few women left without notifying the programme after the drone attack, prompting the organisers to seize the workers' passports for a while.

When asked why the hostel attack and existing reports about Alabuga being at the centre of Russia's drone production had not raised her suspicions, Adau said she had been repeatedly assured by staff that recruits would only work in the fields they had signed up for.

"The allegations that we would be building drones felt to me like anti-Russian propaganda," she explained.

"There is a lot of fake news when it comes to Russia, trying to make Russia look bad. The Special Economic Zone used to have people working there from Europe and America, but they all left after the Ukraine-Russia war because of the sanctions on Russia. So when Russia started looking for Africans to work there, it felt like they were just trying to fill up the spots the Europeans left."

After Adau handed in her notice, her family sent her a ticket home, but she says many women cannot afford to pay for a return flight and end up stuck there - particularly because their pay is much lower than advertised. Adau was meant to earn $600 (£450) per month, but only got a sixth of that.

"They deducted money for our rent, for our Russian classes, for the Wi-Fi, for our transport to work, for taxes. And then they also said that if we skipped a day of work, they'd deduct $50. If we set off the fire alarm whilst cooking, they'd deduct $60. If we didn't hand in our Russian language homework, or if we skipped class, they'd deduct from your salary."

The Alabuga Start programme told the BBC that salaries partly depended on performance and behaviour in the workplace.

We spoke to another woman on the programme who did not want to be named for fear of reprisals on social media. She says she had a more positive experience at Alabuga.

"To be honest every company has rules. How can they pay you your full salary if you miss work, or don't perform well? Everything is logical, no-one is subjected to what they do not want. Most of the girls who end up leaving missed work and didn't follow the rules. Alabuga doesn't hold anyone hostage, you can leave at any time," the unnamed woman told the BBC.

But Adau says working for Russia's war machine was devastating.

"It felt terrible. There was a time when I got back to my hostel and I cried. I thought to myself: 'I can't believe this is what I'm doing now.' It felt horrible having a hand in constructing something that is taking so many lives."

Additional reporting by Ed Habershon

Get in touch

If you have information about this story that you would like to share with us please get in touch.

You may also be interested in:

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

BBC Africa podcasts

- Attribution