Listen to Tom reading this article

Kate Wareing has dedicated her career to helping people who find themselves in a crisis because they have nowhere to live.

It's clearly personal. She worked as a housing officer at the age of 18, remembers sleeping on a sofa herself when a relationship broke up, and now in her early 50s, feels she is only a home owner because of "luck and age".

"Everybody needs the security of a home," she says. And now Kate, who is the chief executive of an Oxfordshire housing association, has an idea that she thinks could help the government with one of its most pressing challenges: how to empty asylum hotels by 2029.

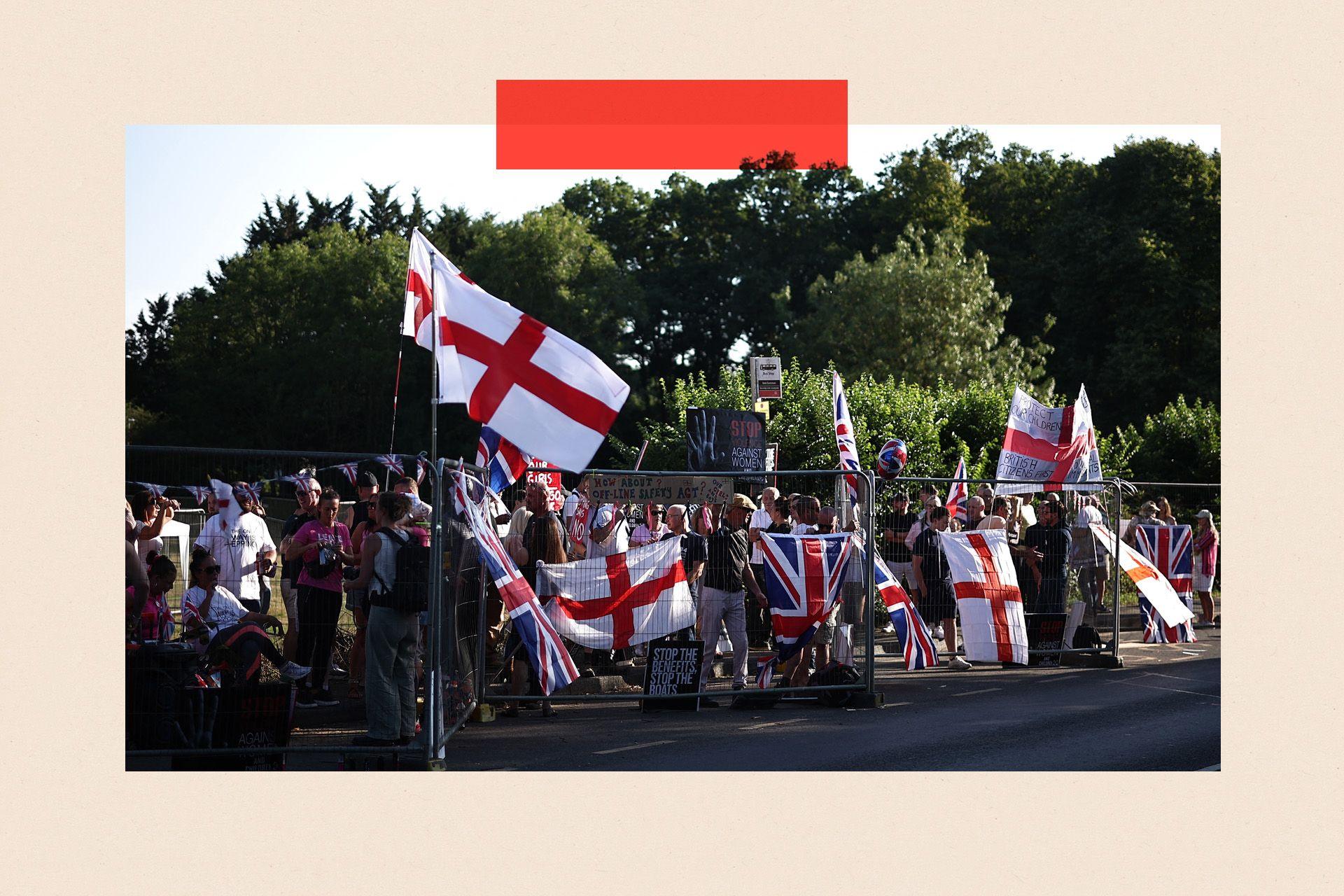

The pledge to empty them was made by Labour when tensions and anger rose during the summer, in communities where some regard asylum seekers as a threat to local safety.

The cost of putting asylum seekers in local hotels is also "cripplingly expensive," points out Kate - and she makes a bold claim: the cost could be cut from about £54,000 a year to just £4,000, for each asylum seeker, by moving them to social housing.

Protests and counter-protests outside the Bell Hotel in Epping

Instead of paying private contractors to provide hotel rooms, as it does now, she wants the government to pay councils and housing associations to buy more properties, adding them to the nation's social housing stock, to benefit migrants and others in need of a home.

The BBC has been told her proposal has been discussed with several government departments, including the Treasury and the Home Office.

Officials are talking to nearly 200 councils about a series of pilot projects, though the Home Office won't give details.

The question is, could it really work - if private companies haven't managed to source enough accommodation for asylum seekers, what's to say a council could?

Under Kate Wareing's plan, the government would give a council or housing association an average of £80,000 to buy and do up a property

And would this alternative really help to calm the strident public debate, in the wake of the protests and counter-protests outside the Bell Hotel in Epping and elsewhere - or might it exacerbate it?

The pandemic fuelled the problem

There is no doubt tensions have been increasing.

In July 2015 a coastguard in Dover told the BBC that two migrants had been rescued from a dinghy just offshore in the Channel. It was so surprising that it made the news.

At that time people typically hid in lorries to get across the Channel. But during the Covid-19 pandemic, there were fewer lorries and would-be stowaways increasingly began using inflatable boats instead.

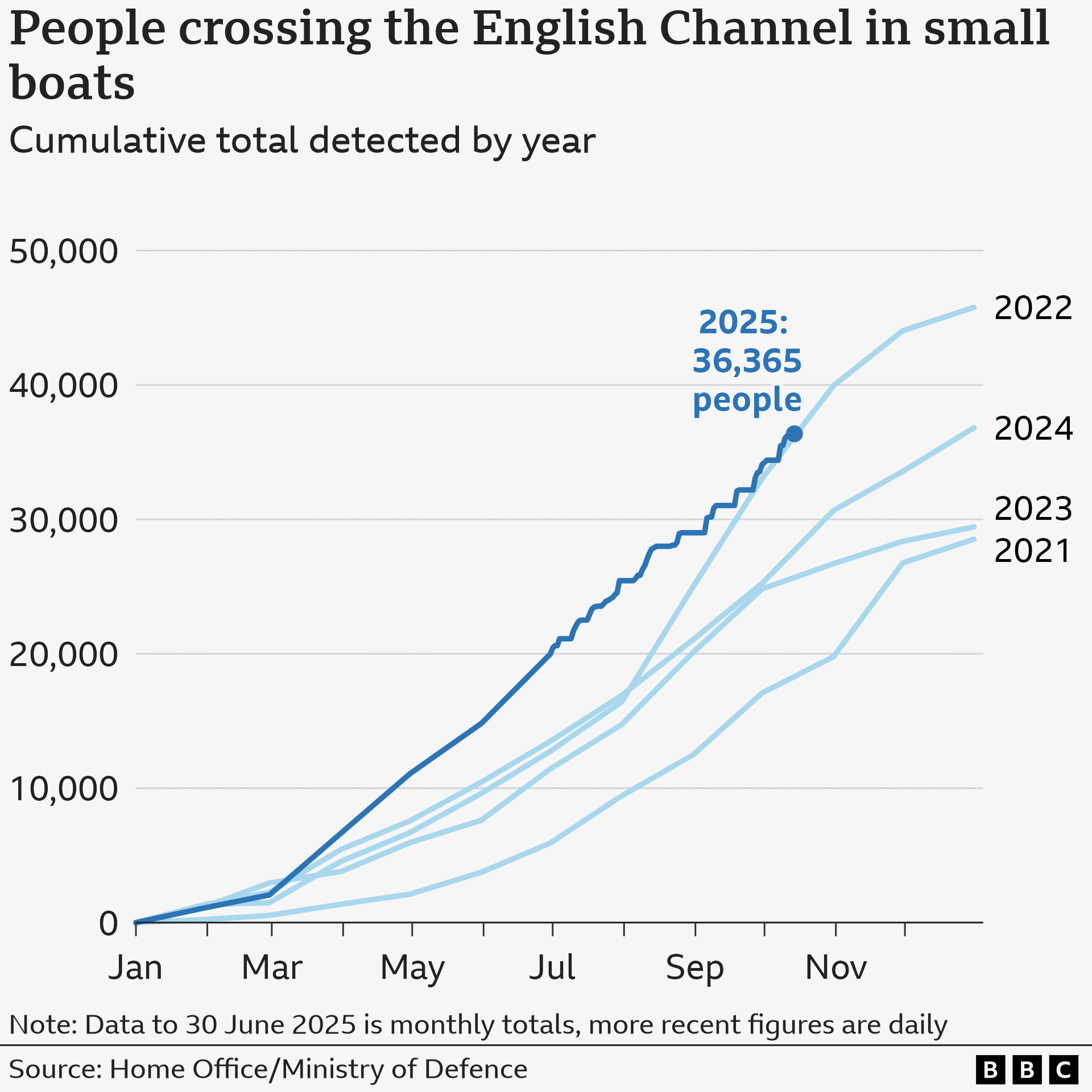

Small boat arrivals accounted for a relatively small 4% of total immigration to the UK for the year to June 2025, but the numbers are rising.

The pandemic also rapidly increased the use of hotels to house asylum seekers.

Successive administrations have banned asylum seekers from working for their first year in the UK - they didn't want the opportunity for a job to become a "pull factor" - so it falls to the government to support them.

The Conservatives turned to the private sector for help, handing contracts to three companies - Serco, Clearsprings Ready Homes and Mears - to provide beds.

The problem was, they ran out.

Then, as lockdowns struck, hotels emptied, providing a useful source of emergency accommodation. The rooms are, however, more expensive than renting houses. In October 2025, the government was spending £5.5m per day on them.

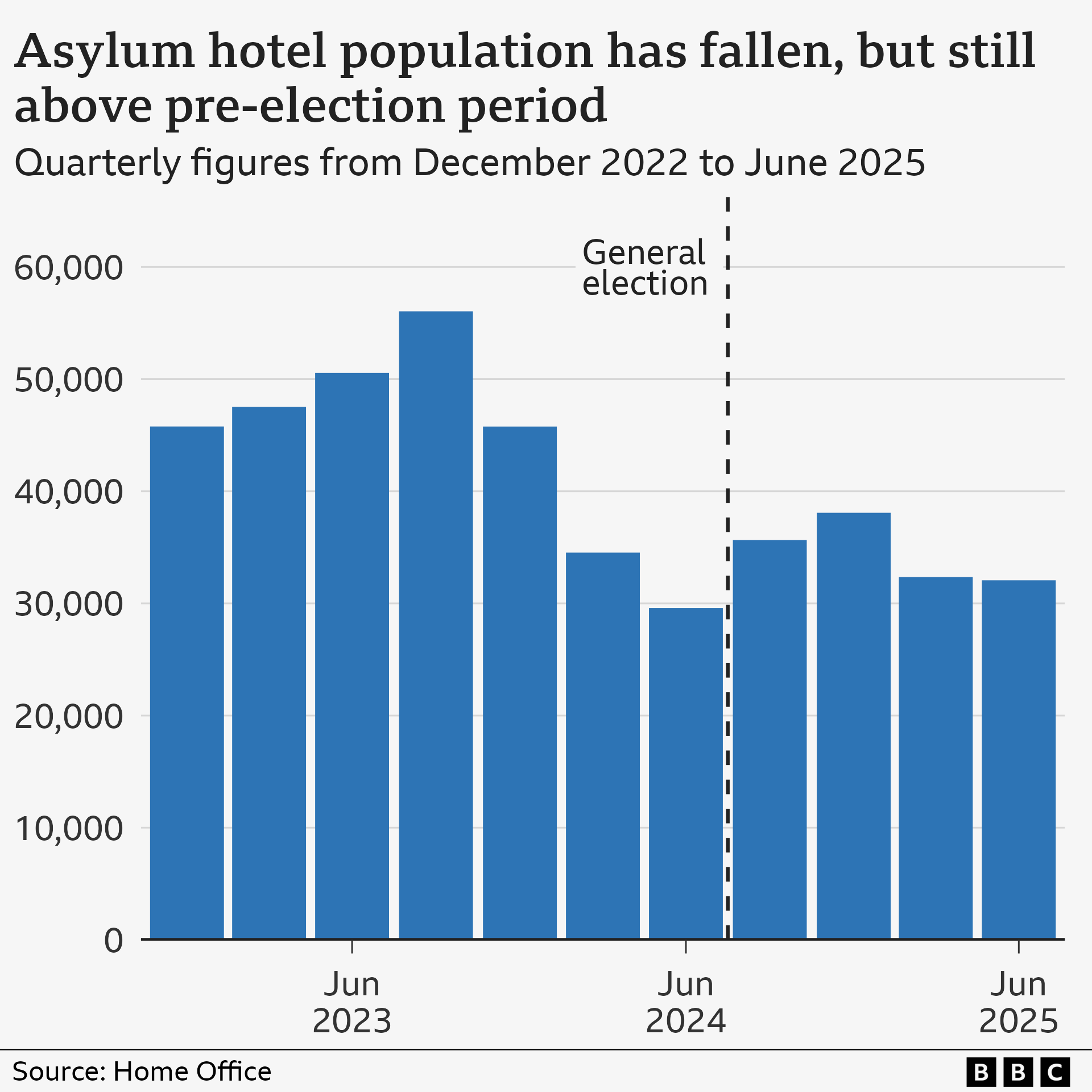

At one point, under the Conservatives, there were 400 hotels in use but they managed to reduce the number over time.

While Labour has closed three hotels since July 2024, there are still 210, housing around 32,000 people.

'Put them in a camp'

This summer, the argument moved to the streets, with protesters demanding the closure of asylum hotels.

Lorraine Cavanagh, campaigning outside the Britannia Hotel in London's Canary Wharf, told me: "I don't know who they are. They have no background, they have no passports, they are unidentified men who can walk around and do what they want to do with no consequences.

"Their beliefs are not the same as ours. They are coming in and trying to disturb and change things, that we are not used to."

Several protests about asylum hotels have taken place across the country, including in Canary Wharf, London

Some protesters have another suggestion: put them in a military camp.

Rakib Ehsan, a senior fellow at the centre-right Policy Exchange think tank, agrees this could be useful on a temporary basis.

"At least they would be somewhat separated from local communities," he says.

Two large former Ministry of Defence sites are currently being used for asylum seekers - Napier Barracks, near Folkestone, and a former RAF base at Wethersfield in Essex.

In 2021 the High Court found Napier Barracks, which is capable of housing 300 male migrants, to be overcrowded and filthy, requiring the government to take action.

The other facility, Wethersfield, which contains bedrooms, recreational areas and places for worship, is being expanded. Eventually more than 1,200 beds will be available.

Residents can come and go, but the High Court was previously told Wethersfield was like a prison. Three migrants bringing a case against the former Home Secretary described "tensions and outbreaks of violence" within its walls.

These "large sites" are not cheap either. The government spent £49m refurbishing Wethersfield, far more than had been estimated.

A programme to open accommodation at RAF Scampton was also abandoned in 2024 after the cost ballooned to £60m.

The public financial watchdog, the National Audit Office, concluded in March 2024 that these large sites would cost even more than hotels.

Questioned by MPs in June 2025, the Environment Minister Angela Eagle said the government was moving away from "asbestos-filled buildings, poisoned land, unexploded ordinance and all those sorts of things on old army bases".

But then in September 2025, Defence Secretary John Healey popped up, during the wave of anti-migrant protests, and revealed he had tasked his planners with identifying more military sites.

Did the need for beds become greater, or did the rhetoric around using barracks for people who claim to be fleeing persecution become more acceptable, as Reform edged up in the opinion polls? Possibly both. Plans are yet to be revealed.

Either way, what the government really needs now, is lots of cheaper, and better places for them to stay.

Private sector problem

Hotels and military bases are used for "emergency accommodation" when there isn't enough so-called "dispersal accommodation" in communities around the country, which often takes the form of Houses in Multiple Occupation, or HMOs.

This is where at least three people "not from the same household", live together, sharing a bathroom and a kitchen.

Three main private contractors use public money to find HMOs on the open market. One, Mears, went on a spending spree across the north-east of England in 2023 and early 2024 buying 221 properties for more than £20m. But many flats and houses are rented from private landlords.

Another provider, Serco, has 1,000 leased properties for asylum accommodation. The third, Clearsprings Ready Homes, has made £187m in the last six years supporting 30,000 migrants, though half of them are in hotels.

So these companies are competing with all of us, and local councils, for suitable properties. Planning applications for HMO status have been rising steadily since 2009, according to the property data company Searchland, though smaller HMOs don't need planning permission.

There can be public opposition to attempts to use HMOs for migrants, just as there is with hotels, which is one factor contributing to a shortage.

Another is that in some areas few rental properties are available at the very low rents the government contracts will pay.

Renting or buying?

This could be seen as a challenge to Kate Wareing's plan for housing associations and councils to provide properties instead. If the three private companies contracted by the government struggle, won't councils and housing associations have the same problem?

"We would shop in a different way," she says.

Often the asylum accommodation companies are looking for the cheapest private rented houses, usually in areas with lots of asylum seekers already, she says, fuelling community tensions.

But councils and housing associations could plan more carefully where to go shopping, she argues, and there are other sources of property they might be able to get hold of more easily.

For example, they could buy up property in housing developments. Builders usually have to offer social housing as part of any new development, in order to get planning permission. There has been a drop in first-time buyers recently.

Small boat arrivals account for a relatively small percentage of total immigration to the UK

"We've got builders approaching us asking if we want to buy more homes on some new-build sites than we would normally be being offered," she says, estimating that might make another 5,000 properties available in the next few years.

Her housing authority alone buys 20 a year, and purchases would be spread across the country. Other experts the BBC spoke to thought this was a reasonable target.

In outline, her plan would work like this: the government gives a council or housing association an average of £80,000 to buy and do up a property. They would also need to borrow some money on top of that, but the interest they pay is usually less than a company would.

More from InDepth

Would leaving the ECHR really 'stop the boats'?

- Published9 October

These properties would be used for current social housing tenants, and when they move out of their existing houses, asylum seekers would move in - after any necessary repairs had been made - with the government paying their rent to the councils and associations to cover their costs.

"We'll have 10 new houses that we can use to relieve some of the needs of our existing residents and then we can also move asylum seekers into any houses that they are vacating," she argues. In the longer term, "there will be 10 more houses to let to the local population or to use for other types of homelessness need."

She calculates an investment of £1.75bn could enable the purchase and renovation of 14,000 to 16,000 homes. The costs of rent would be similar to the cost of the housing benefit asylum seekers are not allowed to claim.

Her analysis was checked by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which has its own model for assessing development opportunities being considered by housing associations. They said it "stood up fine".

'An asylum system in chaos'

Rakib Ehsan of Policy Exchange argues there should be more social housing, but for British citizens not asylum seekers. But Kate Wareing says that under her plan, there would be homes for both.

Rakib Ehsan also emphasises the concerns some people have over public safety, as long as most migrants continue to be young men from "deeply patriarchal societies".

"If we look at the demographic characteristics associated with small boat migrants in particular who went to the UK, they tend to originate from parts of the world which have a very different view when it comes to the treatment of women and girls," he says.

But Kate believes her plan would be politically acceptable, because it makes newly refurbished homes available for local people who need them. Plus she argues asylum seekers could end up sharing a home with others in need, potentially reducing social tensions.

Wethersfield, a former RAF base in Essex, is being expanded

If the government wants to change tack, it has a chance next year, when there is a break point in the 10-year contracts with the three asylum housing providers.

John Perry, policy adviser to the Chartered Institute of Housing says: "That's why this idea has currency. It is very encouraging local authorities appear to want to work with the government."

There is a risk, though, that a version of Kate Wareing's plan would take too long to put into effect, if it is to help the government meet its 2029 deadline.

The Home Office insists the government inherited "an asylum system in chaos" and that it has reduced the backlog of claims by 24%, returned 35,000 people "with no right to be here", and cut hotel spending by over half a billion pounds.

"We are looking at a range of more sustainable, cost-effective and locally led sites including disused accommodation, industrial and ex-military sites, so we can reduce the impact on communities and taxpayers," a spokesperson said.

If the government can meet its pledge to close the asylum hotels, the prize would be saving of £1bn per year, according to the Chancellor, Rachel Reeves.

But failure would give the government's main opponent, Reform, a big stick with which to beat it, at the next election. This issue could help decide the outcome.

Top picture credits: PA Wire/ EPA/Shutterstock

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.