Clean Bandit: We were told to stop making pop music

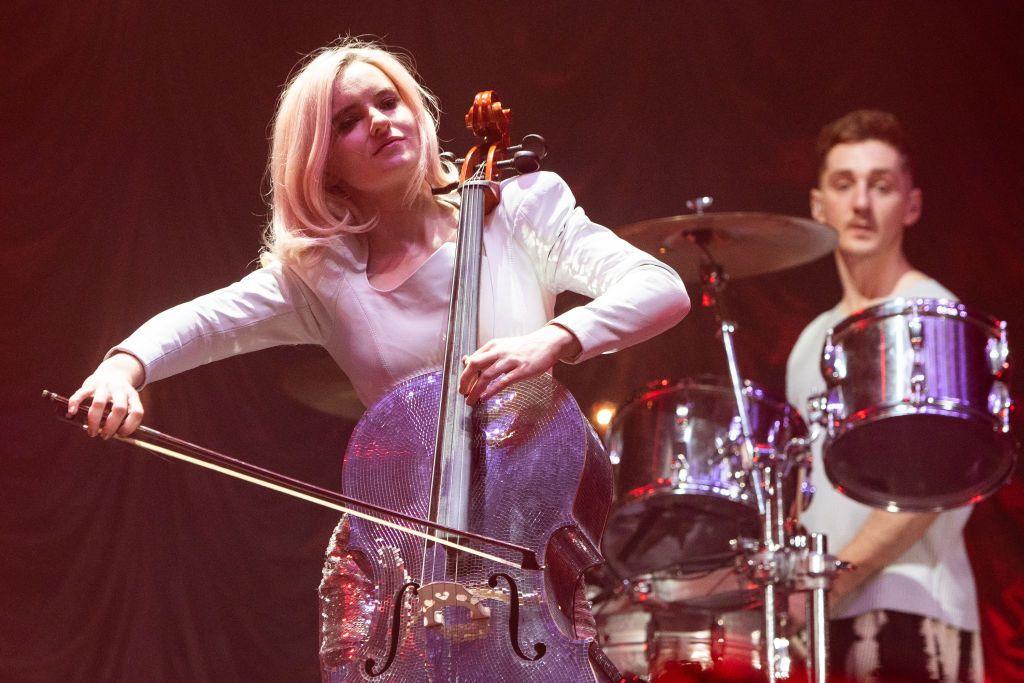

Clean Bandit (Clockwise from top): Jack Patterson, Luke Patterson and Grace Chatto

- Published

Discovering a signature sound is the holy grail of pop music.

There’s no Pink Floyd without David Gilmour’s sweeping guitar lines. Remove Dr Dre's incendiary production, and NWA's lyrics lose some of their potency. Billie Eilish’s vocal delivery is so distinctive she can jump between genres without losing her essence.

For Clean Bandit, their signature sound is a simple, but effective, mixture of chamber music and dance beats.

It’s a formula they came up with at university. Cellist Grace Chatto was dating architecture student Jack Patterson, who started splicing samples of her string quartet into his instrumentals.

It wasn’t exactly a new idea. In 1976, Walter Murphy turned Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 into a thumping disco track; and in 1995, Madonna's producer William Orbit made an album, Pieces In A Modern Style, that took Ravel, Vivaldi and Handel to an all-night rave.

But Clean Bandit weren’t interested in remixes. They wrote big pop hits like Solo and Rockabye, using their classical chops to give the songs emotional heft.

“It’s a delicate balance,” says Patterson. “If you added a sax solo, for example, it’d be one element too far. You might as well put on a waistcoat and go home.”

But when it works, it works.

Clean Bandit’s trademark sound earned them four UK number one singles, two Ivor Novello songwriting awards and a Grammy.

Then, with grim inevitability, their record label told them to ditch it.

“There was a push for us to stop having strings in our music,” grimaces Chatto.

“We were told to stop making pop music, as well,” says Patterson.

“We were sent dance music playlists on Spotify and told ‘your music has to sit on here - only Harry Styles can make pop music’.”

Four of the band's songs have surpassed one billion streams on Spotify - Rockabye, Rather Be, Solo and Symphony

Part of the concern was that the band are, in their own words, “shy and unassuming people”.

Their songs are fronted by pop titans from Demi Lovato and Ellie Goulding to Charli XCX and Lizzo - but the trio (completed by Jack's brother Luke) can still catch the Tube without being bothered.

“We were told ‘you don’t have a face, you need to make club music',” recalls Patterson.

The demands were so frequent and insistent that the band began to mistrust their instincts. They erased the violins and went for a darker sound, more indebted to house than pop.

It did not go well: Since 2020, none of their records has made the top 10.

Jobs on the line

“We allowed it to happen because we were like, ‘We'd rather release something than nothing’,” says Chatto.

“But the music didn’t feel like our music. Our fans were feeling it. We were feeling it.

"In the end, we were like, what's the point in doing anything?’

Eventually, they negotiated an “amicable” exit from Atlantic Records that allowed them to retain the rights to all of their unreleased songs.

“It couldn’t have ended in a better way,” says Chatto.

“We’re still friends with those people... I just think the more success we had, the more pressure they felt. Their jobs were on the line.”

The band jumped over to the Sony Music label B1/Ministry of Sound, whose head honcho is Wolfgang Boss - one of the first people to champion Clean Bandit back in the 2010s.

He encouraged them to release Cry Baby – a collaboration with Anne-Marie and David Guetta that they’d been sitting on for four years after Atlantic rejected it.

From the opening bars, it’s undeniably a Clean Bandit song. Chatto whistles a Spaghetti Western hook over sweeping strings, before Anne-Marie delivers a salty lyric about a cheating boyfriend over a breezy, tropical beat .

“It feels like a comeback,” says Chatto.

The band have traditionally designed all their own artwork and shot their own music videos

It’s not just the music. The band got back into the habit of directing and filming their own videos - something they’d not done for a couple of years.

For Cry Baby, they dreamt up an epic storyline, in which Anne-Marie flees her disloyal partner on a long distance luxury train. But when they brought the storyboards to production companies, they turned it down.

“They said it would cost at least a quarter of a million pounds,” says Chatto, “so I ended up producing it myself, which is a first.”

That meant commissioning and building the sets at their own expense.

Luckily, Chatto’s father is a carpenter, who not only built her first cello, but also happens to work on the London Underground (“It was his idea to put sliding doors on the platform of the Jubilee line,” says Patterson).

And so Ricky Chatto found himself constructing a complete dining car and sleeper carriage inside Clean Bandit’s studio in Finsbury Park.

“He didn’t realise what we were letting him in for,” laughs Chatto. “We tried about a million different varnishes. It was epic.”

Patterson directed and edited the video, which also features a horseback-riding stuntman who dives through a train window; and a near-death experience for David Guetta, after a contraption that was supposed to simulate tears malfunctioned while strapped to his face.

Undeterred, the group are planning an even bigger shoot for their next single, which sees them reunite with Swedish pop star Zara Larsson.

Grace's father Ricky cameos in the video for Cry Baby, after helping to build the set

“Zara’s been learning to fly helicopters,” reveals Patterson. “So we're devising a story where she works for the RAF search and rescue as a helicopter pilot.”

The band seem creatively reinvigorated after a period they politely describe as “pretty challenging”. They have two albums-worth of material ready to go, including unreleased collaborations with Elton John and Raye that may (or may not) see the light of day.

They’ve also been spreading their wings, collaborating with artists from South America, Jamaica and Africa on a number of spontaneous sessions earlier this year.

Unexpectedly, those sessions were inspired by another teeth-grinding setback the band endured in 2019.

It all started when the band signed a deal with a major beer company, who offered to sponsor the band as they travelled to China, Russia, Nepal, India and Vietnam, making new songs with local artists.

“They approached us and said ‘you have total creative freedom’,” says Patterson. “As long as you drink a bit of the beer in the studio, we'll pay for it all and film it.”

“It felt like it was going to be a really creative thing – but we’d been tricked,” adds Chatto.

The band have been writing and recording all over the world ahead of the release of their third album, with sessions in Nigeria, Jamaica and Mexico (pictured)

The penny didn’t drop until their third recording session, when the band were handed a translation of the lyrics by Vietnamese singers JustaTee and Phương Ly.

“I was like ‘that’s weird, the chorus says “open to more” again’,” recalls Patterson.

It transpired that, although Clean Bandit had been given artistic freedom, the brewery had signed separate contracts with their collaborators, forcing them to use the company’s slogan in their lyrics.

‘We were like, ‘hang on, that’s the Tuborg strapline, why are you writing that in the chorus?’” Patterson recalls.

“And they're like, ‘oh, we have to. If we don't do that, we don't get paid’.”

The whole experience was a “devastating waste of energy”, he says. The songs essentially vanished, unable to be played on radio stations where they’d be considered in breach of advertising guidelines.

But, says Chatto, “it made us realise that if we were doing this on our own terms, it would be a fantastic way to live - just going around the world, making music.”

That’s what they did at the start of 2024, with writing sessions in Miami, Lagos and Jamaica that have produced “two entire records” of material.

Some of those songs have already come out – including the sublime summer jam Mar Azul, written with Colombian pop group Piso 21.

“I hate to keep coming back to it, but our previous label was based in the UK,” says Patterson, “so their priority was always what would work over here.

“If it wasn’t going to be played on Capital [Radio], they weren’t interested.

“Now, if we work with someone in Mumbai, that’s ok. The fact that we don’t have a singer means we can be light on our feet and work anywhere in the world.”

That’s where Clean Bandit see their future: Concentrating on quality, rather than the demands of streaming algorithms, in the hope their fans will follow them.

“That’s the hope,” says Chatto. “Because it’s already been the case that our songs have gone around the world and reached a lot of people.”

In other words: There’s no place they’d rather be.