Bowen: Gaza nurse who filmed moments after Israeli strike describes chaos and grief

Paramedic Nevine al Dawawi says Jabalia has been "besieged" by Israeli forces

- Published

From the outside, it is hard to comprehend the depth of suffering experienced by civilians in Gaza.

On Monday 21 October, a video emerged from Jabalia that gave an unusually detailed insight into the pressure and the horror imposed on civilians by Israel’s current offensive in northern Gaza. Watching it, you feel almost like an eyewitness.

Every day, like many journalists who are forced to report the war from outside Gaza because Israel will not let us in, I watch many videos that emerge online, harrowing scenes of wounded, dying and bereaved people in hospitals, of men in the rubble rescuing survivors and digging out bodies, and civilians forced to move by the Israelis, walking through thick sand where roads used to be, past the unrecognisable ruins.

They are all horrible to see, and so was the one that came from the attack in Jabalia on Monday morning. But for me it was unusual because it showed the pain, grief, chaos, panic and hopelessness in the seconds and minutes immediately after an attack.

The moment is so extreme that taking out a phone to film it is the last thing most people do. Over many years as a reporter in wars, I have seen and experienced the same disbelief and shock. It takes time for the brain to catch up with the utterly changed reality that your eyes are seeing.

The Jabalia Boys Elementary school was attacked just after 09:00 in the morning, on 21 October. It was no longer a place of learning but had been turned into a shelter for displaced civilians, like many schools in Gaza run by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees. All the ones still standing, that is.

In the video, a paramedic called Nevine al Dawawi, increasingly panic-stricken, runs between dead and dying civilians, using her phone to document what is happening (when I reported this first, on the day of the strike, she was misidentified as Nabila.)

We managed to track down Nevine in Gaza City. She was able to give us her own account of what happened on Monday morning. She answered questions, and much more composed now, she played back the video.

In it, she is agitated and scared, running between civilians lying in their own blood, next to dead bodies.

This story contains some distressing details from this point

'I don't have anything to stop the bleeding'

“Calm down,” she screams at a badly hurt woman sitting in a pool of blood.

“I swear I don’t have anything to stop the bleeding.”

She runs down a passage pockmarked by shrapnel. On a stairwell she sees more casualties, turns away in horror, picks up a bag and says "let’s go, so no-one else gets killed".

A man’s voice on the video says, “stay with us Nevine.” Grabbing the bag, which is full of wound dressings, she goes back to the stairwell that is running with blood. A child’s voice says, please help, my sister is dying, please help me.

A woman says my children are gone. Nevine asked how she knew.

“Look at them,” the woman says. One is very still, the other has a severe head wound and is either dead or dying.

Nevine hands over dressings, even though it is too late. They are all she has, and she is the only paramedic there.

Nevine told us that the woman on the stairs whose children were killed was Lina Ibrahim Abu Namos. Journalists working for the BBC found her in Kamal Adwan hospital in Jabalia where she is being treated for shrapnel injuries. Two of Lina’s seven children were killed, her eldest daughter and her only son.

Her husband wasn’t with them when the attack happened, as he was already being treated for wounds sustained in an earlier attack.

“I saw my daughter dying, with my own eyes. She was dying in front of me. I couldn't stop it, and she was my eldest, my whole life, honestly, my entire life. When your eldest dies in front of you…”

“I couldn’t save her, and I was also wounded. I couldn’t handle myself, I found myself falling on the ground. I started crawling towards her.”

Lina Ibrahim Abu Namos has lost two of her children since the war started

Nevine, the paramedic, explained that they had been "besieged" at the school for 16 or 17 days. Above them was the buzz of quadcopters, small drones used extensively by the IDF. It has a range of them, for surveillance and espionage, to issue orders through loudspeakers, for dropping bombs or firing at Palestinians they want to kill.

“We were living in so much fear. When the school was hit, we had people killed and injured. There was nothing there to eat or drink. The water tanker that was usually sent to us was bombed by the Israelis. It was like that for days. Three days ago, a quadcopter descended on the school at nine in the morning, giving us an ultimatum to get out by 10. The quadcopter loudspeaker said we had to evacuate the school because we were in a dangerous fighting zone.”

“We didn’t have time to pack our stuff. It gave us just one hour. After just 10 minutes, Israeli airplanes bombed the school. It was a big massacre with over 30 wounded and more than 10 killed.”

In the video, the wounded and dead on the bloody stairs are not the only casualties. Nevine leaves the stairwell, and runs to a man probably in his sixties, who is leaning over a pile of bags with his head in his hands. She looks to see if somehow, he has survived a severe neck wound and screams when she sees that he has not.

“Help him, he’s dead – it’s Uncle Abu Mohammed.”

Three days later I sent questions for a Palestinian freelance journalist to ask her at al Ahli hospital in Gaza City. One was about Abu Mohammed.

“He was our neighbour. His two sons were also killed… one had half his head gone.”

She talked our reporter through the video as she played it back on her phone.

“The video showed girls torn to pieces. It also shows men with their intestines protruding from stomach wounds… A 10-year-old boy had his bowels bulging outside his stomach. His mum was killed, injured in the heart.”

“Some women who were taking cover were also injured and others killed. A cleaner at the school was shredded into pieces. A 12-year-old girl had a leg blown off. So did a woman displaced from Beit Hanoun, a town in Gaza’s north. She was aged between 35 and 40.”

The day before the attack on the school, as Israel’s offensive intensified, Tor Wennesland - the senior UN diplomat in Jerusalem - issued a strong statement.

“The nightmare in Gaza is intensifying. Horrifying scenes are unfolding in the northern Strip amidst conflict, relentless Israeli strikes and an ever-worsening humanitarian crisis.”

“Nowhere is safe in Gaza. I condemn the continuing attacks on civilians. This war must end, the hostages held by Hamas must be freed, the displacement of Palestinians must cease, and civilians must be protected wherever they are. Humanitarian aid must be delivered unimpeded.”

Israel insists that it acts in self-defence, and claims its forces respect the laws of war. Almost every day for the last year in Gaza, and more recently in Lebanon it says that civilians get killed because armed groups use them as human shields.

We put that to the paramedic, Nevine al Dawawi.

The IDF claimed Hamas was using civilians as human shields, is that true?

“No, Hamas was not using civilians as human shields. They were protecting us and standing with us.”

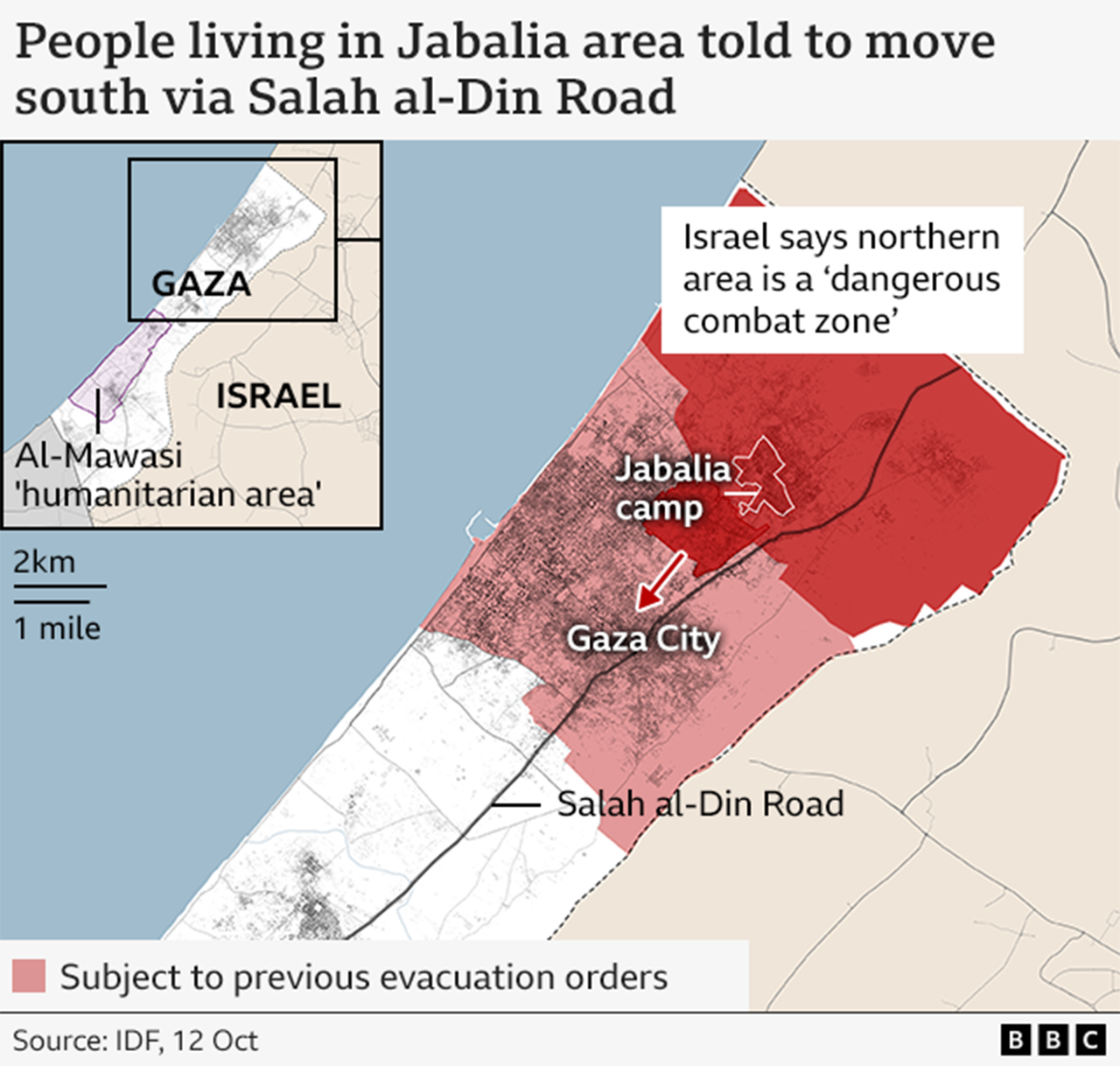

Families fleeing Israeli army operations in Jabalia take the main Salah al-Din road towards Gaza City on 23 October.

For many in Israel, her statement that Hamas were in the area will be taken as a justification for the horrors that the IDF brought down on the civilians just after 9 in the morning on Monday 21 October.

But war crimes lawyers will ask whether the attack was justified. The laws of war say that civilians must be protected, and that casualties inflicted on them should be in proportion to the military threat faced by an attacking force.

If senior Hamas commanders were there, or a big concentration of fighters preparing to fight, perhaps the attack could be justified by the Israel Defense Forces’ own lawyers.

But if Hamas, whose structure as a fighting force has been dismantled in a year of relentless Israeli attacks, had only a few local men with guns in the area, then the attack would breach the law.

In the unlikely event that the Palestinians in the video ever had a day in court, their lawyers could say that the military threat to the IDF at that moment did not justify wounding 30 civilians, inflicting life changing injuries, and killing more than 10 others, including many children.

I am forced to use conditional tenses because I am writing this in Jerusalem, not after interviewing eyewitnesses at the scene of the attack in Jabalia in Gaza. Reporters will always struggle to get to get to the best possible version of the truth they can find when they are stopped from getting to the place where the story happened.

Israel allowed reporters into their border communities along the border with Gaza in the days after the Hamas attacks last year. I was in Kfar Azza kibbutz when they were still recovering the bodies of dead Israelis, as soldiers checked buildings with bursts of gunfire. They wanted us to see where Hamas had killed around 1,200 Israelis, mostly civilians, and dragged more than 250 into captivity in Gaza.

The evidence is piling up that Israel has done things in Gaza that it does not want journalists to see, which is why they will not let us cross into the territory, except on rare and highly controlled visits with the army. I have been in only once, in the first month of the war, when Israeli firepower had already turned the areas of northern Gaza that I saw into a wasteland.

As a result, journalists rely on videos and statements that emerge from Palestinians inside Gaza, including some very brave journalists, and from international diplomats, medics and aid workers who are allowed into Gaza, and witnesses like Nevine with smartphones.

In the hospital, Lina Ibrahim Abu Namos was haunted by her loss of her eldest daughter, her only son, and everything they called home.

“I had seven children, and now I only have five left… What can I say? I don’t even know. By God, they have broken our hearts. We are exhausted, emotionally drained. We’ve lost everything.”

“What crime have the children committed? What have they done? What have we done to deserve this?”

“What have we done to the Israelis? I swear, they’ve destroyed our children.”

"I’m so scared. I don’t eat or drink. Nothing. All I need is for my children to stay around me, because we are scared and we’ve been displaced from one place to another. What is left for my daughters and for me? There’s no home, nowhere safe, nothing. I’m just one of many people with nowhere to go, no safety. I'm exhausted.”