UEA Scientists say polar trip 'really successful'

The RRS Sir David Attenborough which the public had wanted to name Boaty McBoatface has been at sea for six weeks

- Published

Climate researchers on board the RRS Sir David Attenborough have described their latest polar expedition as "really successful".

A team of 40 scientists, led by the University of East Anglia (UEA), have spent the last month conducting research in the Antarctic.

They have been investigating how carbon dioxide moves and transforms from the atmosphere into the Southern Ocean in the hope of improving models that make predictions about climate change.

Some of the work, such as operating underwater gliders, has been carried out remotely, almost 9,000 miles (14,500 km) at the UEA's campus in Norwich.

Prof Karen Heywood, the UEA’s lead principal investigator, said her team had used "every scientific capability the ship had".

"We've been deploying instruments from the ship to profile the ocean, we've been collecting lots of water for analysing and we've been looking at how much krill there is," she said.

"We'll be looking at this data for years to come."

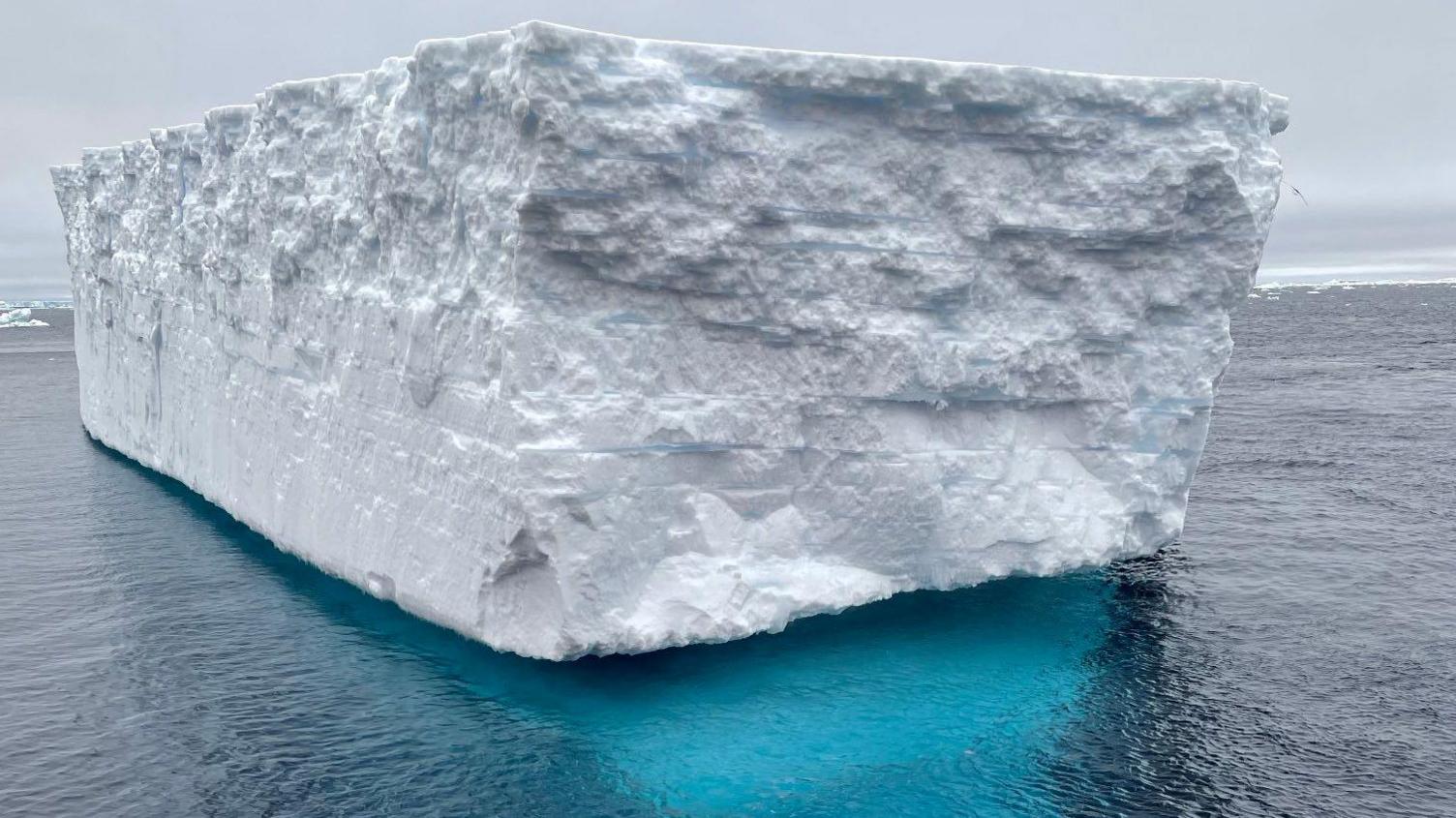

The team has collected samples from parts of the Antarctic which have not been accessed for 20 years

Surface vessels have been used to collect water samples from the sea

A team of UEA researchers first took part in polar trials on board the RRS Sir David Attenborough last year when scientific equipment was tested for the first time.

The £200m ship, run by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), external, became a household name in 2016 when the public voted overwhelmingly to name the vessel Boaty McBoatface, which was later overruled.

Scientists hoped the results from the PICCOLO project, external, would help to inform future decisions on international climate change policy.

The expedition is a collaboration between the UEA, Plymouth Marine Laboratory, BAS, the University of Plymouth, the University of Leeds and the University of St Andrews.

Instruments left in the sea and tagged seals are expected to provide continual data via satellite.

Sea gliders have been used to collect water samples deep in the ocean

Dr Rob Hall, an associate professor in physical oceanography at the UEA has been part of a team operating remote sea gliders in the Antarctic from a university campus in Norwich.

"Sea gliders are like underwater drones, and they glide from the surface of the ocean to the sea bed or to a depth of 1,000 metres," he said.

"They can operate months at a time, anywhere in the ocean, and when they come to the surface they connect to a server via a satellite and we can command and control them from anywhere in the world."

Dr Hall says his team has been on stand-by at all times of the day

The team of scientists are expected to arrive in Chile on 9 March, before returning to the UK.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

- Published9 March 2023

- Published4 December 2023

- Published14 October 2023