Cows, dairy workers, and America's struggle to track bird flu

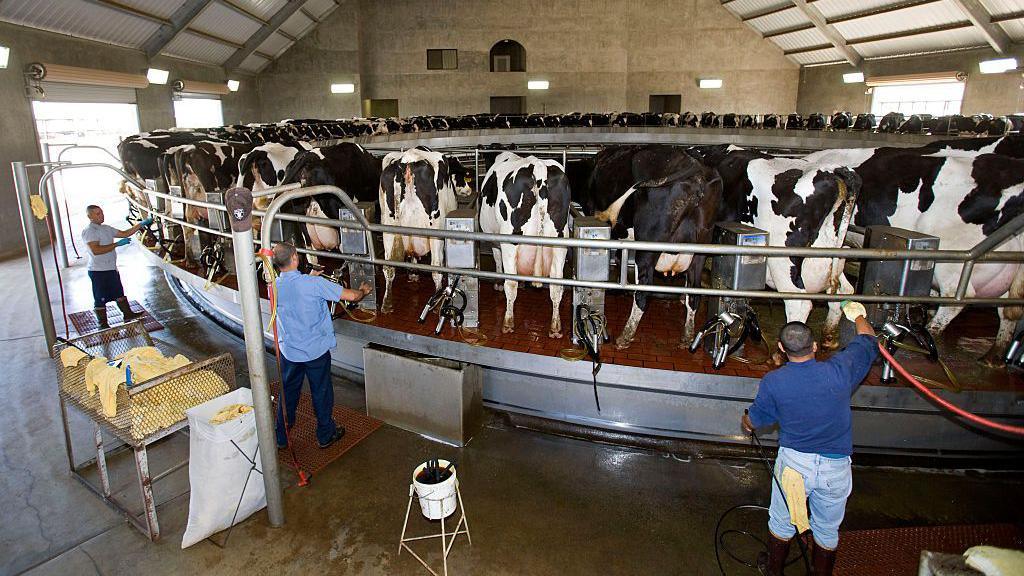

A US farm worker walks between rows of cows being milked at a California farm.

- Published

For the past 12 years, Freddy Morales has worked in close proximity to cows on several of the US's thousands of dairy farms.

But, despite having a job that often requires him to stick medicine down the animals' throats, Mr Morales had not heard of the bird flu virus spreading among American cattle and sickening some dairy workers until very recently.

“I don’t have the immune system I used to have,” the 37-year-old told the BBC through a Spanish translator. “Hearing about this, it’s definitely worrisome.”

There is reason for concern. The disease has found a new foothold in the US by infecting dairy cows and at least 10 people in recent months.

Since April, four dairy workers have tested positive for bird flu, or H5N1, in an outbreak that has been connected to dairy herds in 13 states. Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that another six poultry workers in Colorado tested positive - and the agency is testing a possible seventh case on Tuesday.

US officials have said the strain that infected the poultry workers is closely related to the one infecting cattle and dairy workers, raising concerns about a growing number of infections.

So far, the farm workers' cases have been fairly mild and there have been no documented instances of human-to-human transmission.

But with the virus detected in 161 livestock herds and millions of chickens and turkeys, scientists, advocates, and farm workers worry that these recent cases could indicate that infection numbers are larger than known among the country's 2.6 million farm workers given the lack of regular testing.

Scientists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, testing store-bought milk for the presence of bird flu, which has been detected in New England's milk at low levels.

With the US’s current patchwork monitoring effort that differs state to state, experts said the virus could have more opportunities to mutate into a more severe disease because some areas of the country that have limited testing would not be aware of its presence.

They stressed the need for more preventative measures, testing, and information sharing to keep bird flu from spreading undetected.

Anthony Maresso, a Baylor College of Medicine professor tracking bird flu in Texas wastewater, reiterated the CDC caution that the likelihood of the virus spreading among the general public is “still pretty low”.

He warned, however, that health officials need to remain vigilant as this bird flu variety could be the “tip of the iceberg”.

“What we don’t want to see is the virus evolve to be able to readily infect humans and then transmit amongst us in a way that would cause a global flu pandemic,” he said.

But Rick Naerebout, the chief executive officer of the Idaho Dairymen’s Association, said that farm owners and workers - many of whom are undocumented - are reluctant to allow the government to conduct tests because they fear the agencies may not keep the data confidential.

“There’s not a level of trust there to provide that information,” Mr Naerebout said. “That has been a significant downfall of being able to get testing and being able to get data.”

Bird flu reaches cattle

Bird flu has affected nearly 100 million chickens and turkeys - meaning they either died or were culled to prevent further transmission - since it started to spread among American poultry flocks in January 2022, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported.

But US dairy farmers were caught by surprise in March when the virus began to infect cattle for the first time, with the first documented case in Texas. It has since spread to dairy herds in states throughout the country. Unlike birds, cows with the virus appear to typically suffer more mild symptoms, like fatigue and decreased milk production.

Should I worry about a bird flu pandemic?

- Published18 June 2024

As of now, human symptoms among the four dairy and six poultry workers have also remained fairly minor. They reported issues like conjunctivitis, or pink eye, and some suffered respiratory symptoms more typical of a flu infection.

Mr Maresso and his team at Baylor University have continued to detect the virus in wastewater in 10 Texas cities, suggesting there may be a greater number of bird flu infections than known, however.

“It does raise a little bit of a concern that it's quite prevalent in a lot of different animals, both those that are wild and domesticated, and it’s now interacting at a much more intimate level with our own species,” said Mr Maresso.

The Texas Association of Dairymen, a state dairy industry advocate, has claimed the bird flu had “largely ceased to be an issue in Texas”, and the Texas Department of State Health Services told the BBC that the outbreak among cattle had much improved since March.

But the USDA reported an outbreak in a Texas herd as recently as 8 July, and the state’s health department had previously told Stat News that dairy industry groups had blocked their efforts to better document infection rates by keeping experts from visiting farms.

The farm agency reported that Colorado and Minnesota have the most recent cases of livestock herd infections, with the virus being detected as recently as 19 July.

The ‘complex’ problem of testing workers

Unlike during the early days of the pandemic, the availability of tests is not an impediment to monitoring bird flu’s spread, Demetre Daskalakis, the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC, said.

Mr Daskalakis told the BBC the government has 150,000 tests available and is expecting one million more tests “in the near future”.

The main challenge now is to get farms to agree to the testing of their livestock and their workers.

Worker groups, and employees like Mr Morales, say that farm workers have been told very little about testing, are discouraged from taking sick days and have not been offered personal protective equipment that public health experts say could help guard against the bird flu.

Farm workers working in a rotary milk parlour at a California dairy farm.

“If we were told to use it and it was explained why, I think workers would use it,” Mr Morales said of the protective gear.

Another problem is that many farm workers in the US are undocumented and not offered paid sick days, which keeps them from getting tested or staying home when ill, said Elizabeth Strater, the director of strategic campaigns for the United Farm Workers, an agricultural workers' rights group.

The CDC is offering $75 for farm workers to get tested for bird flu, but that’s not enough to cover costs or lost wages if they have to take a sick day, Ms Strater said.

Farmers: a ‘hard nut to crack’

Another challenge for bird flu monitoring are the economic realities of US agriculture and the growing number of financial strains that have particularly affected dairy farms.

American dairy farmers have struggled more than most in US agriculture, causing the number of the country’s dairy farms to decline rapidly over the past 50 years. The country boasted 650,000 farms in 1970, according to USDA data, but only 32,000 remained in 2020.

With tighter margins, many farmers view any additional financial hardship - which the bird flu could bring - as an existential threat.

Mr Naerebout of the Idaho Dairymen’s Association said that this makes it difficult for farmers to trust government agencies. He said many are choosing to handle outbreaks on their own, without consulting health or other government agencies.

“Out of concern for privacy and out of concern for their ongoing business, they manage through it, get to the other side and keep doing their thing,” Mr Naerebout said.

According to US agriculture data, the number of dairy farms has declined rapidly and the size of dairy cow herds has grown steadily over the past 50 years.

Dr Daskalakis said the CDC is focused on building “trust in the farm owners as well as trust in workers” to ensure they feel comfortable connecting with local health agencies.

But, he added, “that, in general, is a really hard nut to crack”.

Eric Deeble, a USDA official, told reporters last month that the agency is working on programmes that it anticipated would lead to a “surge” in the number of farms participating in a variety of USDA bird flu support programmes.

The USDA also told the BBC in a statement that it intends to pay farmers “90 percent of lost production per cow” due to bird flu infections for “a set period of time”.

But Mr Neurebout said that few farmers believe that the USDA could sufficiently reimburse dairy - especially as herd sizes in the US have spiked.

“For our larger Western herds, you’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars,” he said.

Keeping 'the virus from gaining traction’

While several states face roadblocks to increasing monitoring efforts, some states have found success by building trust within farm communities.

Michigan has received much praise for its work to connect public health officials with dairy farms, which has led to increased testing rates. It is also participating in a CDC study to assess infection risk for dairy workers and the potential for there to be asymptomatic cases.

The state does have a high number of bird flu cases - which includes two dairy workers - but scientists and public health officials argue that this corresponds to the effort they have put in to monitor the virus’s spread.

Michigan’s chief medical executive Natasha Bagdasarian told the BBC there is time now to stop bird flu in a way they could not with Covid-19, which spread rapidly and proved highly fatal before vaccines were available.

US pays Moderna $176m to develop bird-flu jab

- Published2 July 2024

“We now have the opportunity to intervene quickly, to prevent a virus from gaining traction within human populations and prevent human-to-human transmission,” she said.

Dr Arnold Monto, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan, acknowledged that the chance of human-to-human transmission remained low. He argued, however, that leaving the situation unaddressed comes with “high potential risk”.

“The only way you can long-term control this is to detect it,” he said. “We really don't know with summer coming on, with state fairs going on, with animals being moved around, that this isn't going to get worse before it gets better, unless we can control it.”