Move to home education biggest since pandemic

Millie helps her mum Kim run a nature group

- Published

A BBC investigation has found the number of children moving to home education in the UK is at its highest level since the pandemic.

Councils received almost 50,000 notifications in the last academic year from families wanting to take their children out of school. This does not include children already being home educated.

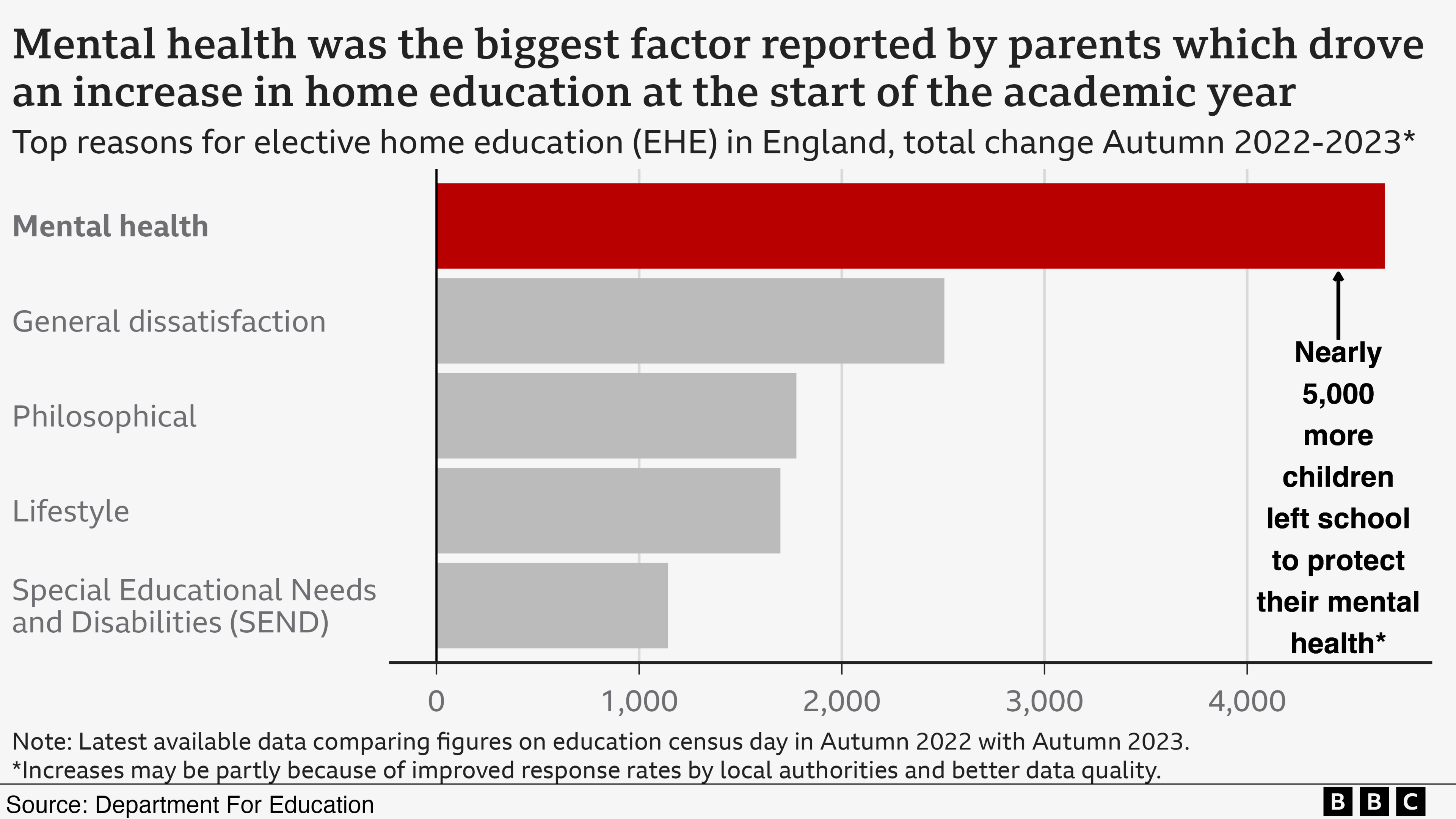

The latest government figures suggest mental health is the biggest reason for the rise.

The Department for Education in England said it supports families choosing to home educate and most do an excellent job, but it was important that it did not risk children falling off the radar, poor education or children's wellbeing.

'Happier in herself'

Dakota enjoys working at her own pace at home

Dakota from Portsmouth moved to home education in February 2024 for her mental wellbeing. She said: “I like learning maths a lot, because it’s more fun and less stressful”. She also enjoys geography, history and creative writing.

The 10-year-old's cerebral palsy means her writing can be slower than other children her age. She said: “I don’t get rushed like I did at school, I’m more relaxed at home.”

Dakota sees friends at a weekly art club and enjoys chatting to them online. She loves doing animation and drawings and wants to be a game designer.

Her dad Clarke, a blind artist who left school at 14, enjoys being Dakota's main teacher, and her mum Anita helps with reading and spelling.

“She’s more happy as she’s more relaxed," Anita said. "The amount of work she’s done since being at home is more than what you do in a year at school. She’s so much happier in herself.”

How has home education changed in your area?

The number of pupils moving to home education has risen by 22% in the past year.

Freedom of Information requests showed UK councils received at least 49,819 notifications in 2022-23 from families wanting to home educate a child.

This is the highest level since 2020-2021, when there were at least 49,851 new notifications.

In the last four years, home education notifications have more than doubled in the North East, North West, West Midlands, Scotland and Wales.

'It was very stressful'

Millie says her mental health has improved since she moved to home education

Millie, 13, from Rotherham moved to home education in February 2021. Her mum Kim, 32, said when schools were shut to most pupils during lockdown, it gave her a taste of how different things could be.

When Millie’s brother became home educated due to his special educational needs, she wanted to join him. She said one reason was her mental health, and that the atmosphere at school "was very stressful”.

Kim said Millie experienced bullying and developed a tic due to anxiety. “When she came out of school, she probably carried on with that for a month or two, and then it just stopped. So she doesn’t really do it now unless she’s under high stress.”

Millie is not planning to do GCSEs, but enjoys studying psychology, foraging and theatre skills. She enjoys spending time with friends at different weekly groups, loves reading and volunteers with women in their 80s at a local bookshop.

Why is home education rising again?

According to government census data, external, there were an estimated 92,000 children in home education in England on census day (Autumn 2023). This was the total number of children being home educated on that day, not just those new to it.

This figure was based on around 95% of English local authorities, and has been adjusted for non-response. It is up by around 11,100 on Autumn 2022.

The census suggested that while the biggest known reason for moving to home education was still philosophical beliefs, mental health was the biggest factor in the recent rise.

The number of families choosing home education because of mental health rose by 64%, from around 7,281 in 2022, to 11,960 in 2023.

Home education in England makes up the bulk of the figures, with at least 46,711 new council notifications in 2022-2023, up from at least 47,008 in 2020-2021.

The biggest rise in new home education notifications in the devolved nations was in Wales. It saw a 17% rise between the pandemic and the last academic year.

A Welsh Government spokesperson said it recognises the right of parents to home educate, but in most cases school is the best place for them. They added that currently, around 1% of children in Wales are home educated.

In Scotland, there was a 3% rise, although the figures for new notifications were the lowest of all the UK nations.

A spokesperson from the Scottish Government said recognising the impact of the pandemic, it is progressing measures to support pupils in schools.

Northern Ireland saw a 13% drop in new home education notifications.

A spokesperson from its Education Authority said during the pandemic, there was a notable rise in the number of children being electively home educated - but it does not hold information on decisions parents made about this.

Wendy Charles-Warner, who chairs the home education charity Education Otherwise, said the UK’s children were going through a "mental health crisis".

She said many parents felt their children’s schools could not meet their needs and they home educated as a last resort.

“They are left with no choice, and every parent should have a genuine choice to choose the best education for their child, whatever that education might be,” she said.

Grainne Hallahan, from the education insights app Teacher Tapp, told the BBC: “Previously there was this given, that children came to school and were educated. That was entirely broken during lockdown, and what we’re trying to do now is fix it.”

Mrs Hallahan said increasing misbehaviour in classrooms could be impacting the recent rise in home education.

She also pointed to higher levels of disadvantage in the north of England, where GCSE results were generally lower, external, and there was a higher percentage of children on Free School Meals, external compared to the South.

Pupil behaviour getting worse, say teachers

- Published28 March 2024

Home-educated child numbers soar by 75%

- Published19 July 2021

More families are asking to teach kids at home

- Published6 June 2024

'He was suicidal at 11'

Charlie from Rochdale started secondary school in 2020, months after the pandemic hit. His mum Victoria said he had had lots of time off due to bullying and violence.

“By the time Charlie had been at his first school four months, he was suicidal – at 11,” she said.

He was in and out of school for three years – sometimes on the school roll, sometimes not. But Victoria did not have the funds to keep home educating him.

Charlie is now at a technical college studying for maths, English and science GCSEs, as well as qualifications in computer science, games design and design and technology.

“He’s loving it, and now has a fantastic big group of friends,” Victoria said. “He stays behind, goes out, goes out at weekends, he’s back to how I thought he would be. But he’s lost three years of his life in the process.”

"No replacement for school"

Alma Harris, Professor of Education at Cardiff Met University, told the BBC: “I’m positive about home schooling if it’s done well. If home schooling is just the young person being at home, it’s not going to help anyone.

“The real danger is some young people can become invisible to the system and potentially unsupported in the system, and there can be some concerns for safeguarding young people’s mental health and wellbeing.”

Professor Harris said there is a balance to take into consideration, especially if a child is experiencing mental health issues or being bullied at school. But she said children who struggle to go to school may also struggle to go into the workplace.

“The school environment is so diverse and the potential opportunities, with the best will, can’t be recreated at home. There is no replacement for school.”

Charts and additional reporting by Miguel Roca-Terry

Get in touch

Are you affected by issues covered in this story?

Related topics

- Published3 June 2024

- Published3 June 2024

- Published3 June 2024

Resources from BBC Bitesize

- Attribution