Irish D-Day Catholics ‘owed great deal of gratitude’

Archbishop Eamon Martin reflected on the service of people from all communities in Ireland

- Published

The role played by Irish Catholics during the D-Day landings in France needs to be remembered, the head of the Catholic Church in Ireland has said.

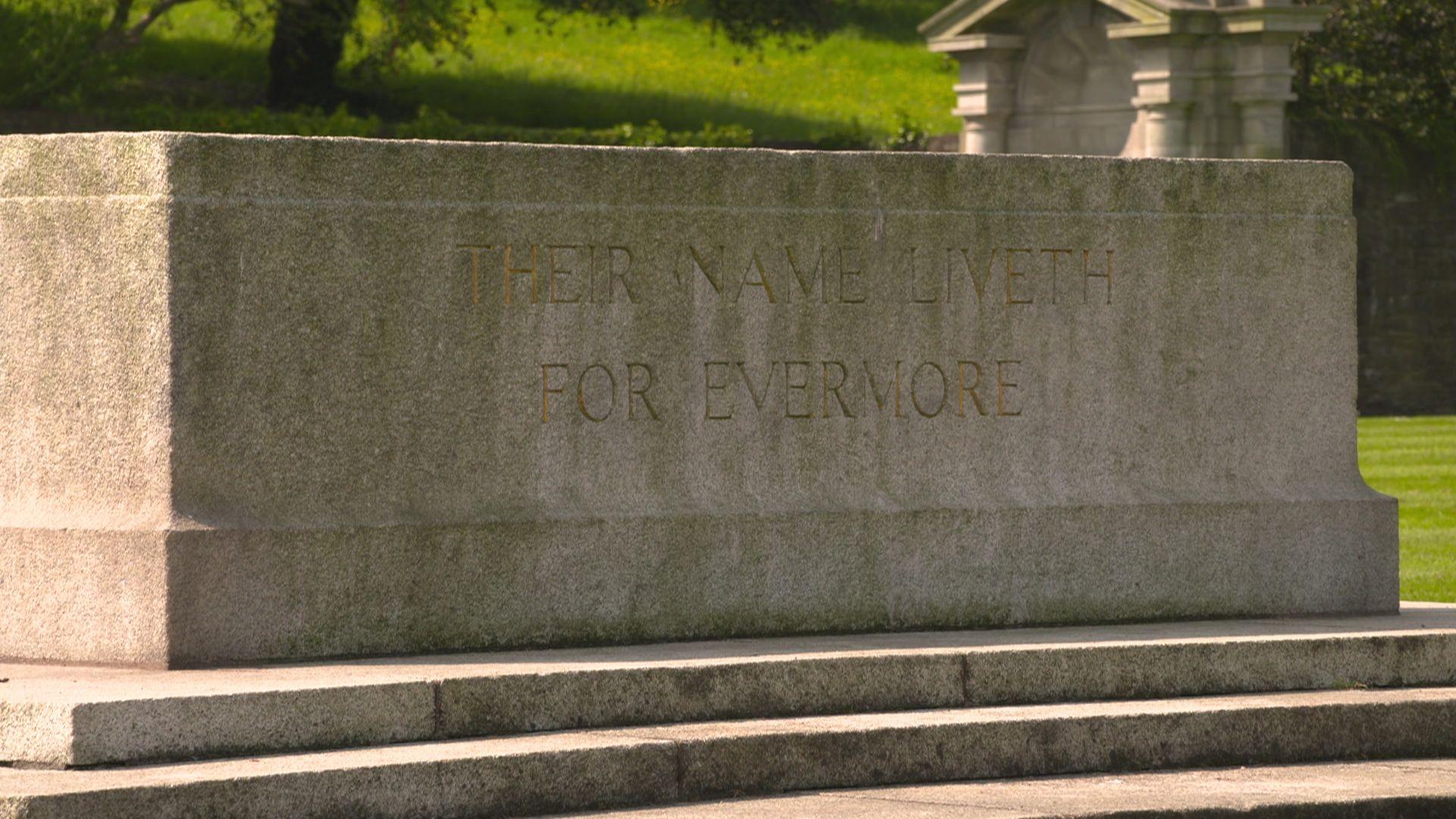

Archbishop Eamon Martin spoke to BBC News NI at Cambes-en-Plaine war cemetery, where a number of Royal Ulster Rifles soldiers who served in the Normandy campaign are buried.

Tens of thousands of soldiers from Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State fought alongside each other in the battle against Nazi Germany.

However, Archbishop Martin said it was sad that many Catholic families do not talk about the role of family members who served in the Allied forces.

He added “everyone owes them a great deal of gratitude”.

“I hope that by being here myself that there are many families who feel that in some way we’re open and recognising the contribution of people from every county on the island.”

Church of Ireland Archbishop John McDowell has also travelled at the invitation of the Royal Irish Regiment to be part of the 80th anniversary commemorations of D-Day.

He said he wanted to hold up the stories of the soldiers and Army chaplains “so people don’t forget” and they are remembered as individuals.

Church of Ireland Archbishop John McDowell said those who served were a remarkable generation

During World War Two, about 130,000 people from the island of Ireland signed up to fight in the British Army.

Half of them were from the Irish Free State, which had declared itself to be neutral.

In Northern Ireland, such was the political division between unionists and nationalists, it was made exempt from conscription.

However, this did not stop many nationalists from joining up.

The 80th anniversary was marked by events in the UK, Ireland and France on Thursday.

Dr Laura Patrick, a heritage officer for the Royal Irish Regiment, said it was difficult to tell the background of those who took part.

Dr Laura Patrick said increasing numbers of nationalists are asking about their war connections

"It's not like the census, there's no tick-box to say exactly where they were coming from," she explained.

"People can be republican, but still want to fight that bigger fight.

"It’s one of the unifying stories of our last 100 years because people saw this as a much greater issue than a north/south issue and a political issue.

"It affected everybody across the world and it was about citizenship of the world, not just of a north/south narrative."

She said for those from a nationalist background "signing up to the Allied Forces sounds much better".

"I don’t think it’s helpful to create those very tight barriers and narratives sometimes. It’s a very grey area."

Michael O’Beirne, from Roscommon, was killed in action and awarded both Irish and British medals

Journalist Allison Morris, who grew up in west Belfast, said British military history “wasn’t spoken about” among nationalist families.

Her great-grandfather was killed in combat and her grandfather had been a soldier pre-1939 before spending three years as a Japanese prisoner of war.

Both of these men were called Thomas Morris.

"My grandmother had thought he [my grandfather] was dead," she added.

Allison Morris has researched her family's military past

Ms Morris explained that nationalists and Catholics felt poorly treated by the Stormont government after the war, meaning "that taints any remembrance that you would have".

"The fact that he [her grandfather] had served and that other people who hadn’t served in the Army were in positions of authority and were discriminating against people like my grandfather who was a war hero," she said.

She also reflected on the fact that she had a cousin who was named Thomas after both men. He was shot dead by a British soldier during the Troubles.

"When you talk about our complicated history and what goes on here, think about that," she said.

"I’m proud of the family I come from."

Commemoration reticence

The Royal Ulster Rifles Museum in Belfast has the medals of a County Roscommon-born soldier who was recognised for his role during the war by the Irish government.

Cpl Michael O’Beirne, 44, who was a tenor with the Royal Carl Rosa Opera Company, served with 2nd Bn Royal Ulster Rifles and was killed on 9 July 1944.

His display contains both his British medals and an Emergency Service medal from Ireland.

Dublin-based historian Diarmaid Ferriter said nationalist soldiers from across the island may have joined for the spirit of adventure, or for economic reasons.

"We know that a private in the Irish Army at the start of the Second World War was being paid 14 shillings a week," he explained.

"If you went into the British Army you were being paid over nine shillings a day.

"There was also those in the Irish Army who did not want to spend the war, given that they were soldiers, not being involved in combat."

Many soldiers in the Irish Free State were co-opted into civil projects, he added, such as turf cutting at Phoenix Park in Dublin.

“Many of them didn’t see that as soldiering.”

In February 1939, then Taoiseach (Irish PM) Éamon de Valera, announced the Irish Free State would be neutral if war was to break out.

In a speech, he said: "With our history, with our experience of the last war and with a part of our country still unjustly severed from us we felt that no other decision and no other policy was possible."

A decade ago, some 6,000 soldiers who deserted the Irish Army to fight for the British during World War Two were granted pardons.

Diarmaid Ferriter said the Queen's visit to Dublin helped change attitudes

According to Professor Ferriter, there is still a reticence about commemorating the role of Irish soldiers during both world wars.

However, he said the public discourse changed with the decade of centenaries and the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Dublin in 2011.

During that trip, she visited both Ireland's Garden of Remembrance and the war memorial at Islandbridge.

"There was a sense the island had to recognise what the people of that generation had been involved in, whether they were unionist or nationalist – and of course sometimes they fought together," he said.

Irish soldiers are remembered at Dublin's Irish National War Memorial Gardens

Dr Patrick said she had also noticed an increase in the number of people from nationalist or republican backgrounds tracing their ancestry.

"People are finding the shoebox in the attic, they’re bringing us sets of medals and saying my grandfather, great-grandfather was from a nationalist or republican background, why did he serve in the British Army?"

"It’s lovely that we can then tell them why they served, what happened to them and what they came home to as well because they don’t like talking about it.

"So we can help shed a little bit of light and a little bit of connection to their ancestors."

What was D-Day?

D-Day was the first day of the invasion of Normandy - the beginning of a huge campaign by the Allies of World War Two in north-west Europe, which was occupied by Nazi Germany.

Along with campaigns elsewhere - including the Eastern Front and the Italian campaign - it would eventually lead to Germany's defeat.

The "D" in "D-Day" simply means "day" - it is a military term used to mark the start of an operation. The hour of attack was known as H-Hour.

Allied troops - mainly from the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States but also other countries - landed on five beaches in Normandy on 6 June.

The Allies suffered about 10,000 casualties - including an estimated 4,000 deaths - but the operation was a success.

Related topics

- Published9 September 2022