St Kilda sea stack scaled for first time since 1890

- Image source, Ryan Balharry

Image caption, Climbers, including Edinburgh's Robbie Phillips, on a sea stack known as The Thumb earlier this year.

1 of 7

- Published

A rock climb in remote St Kilda first described by a Gaelic scholar more than 300 years ago has been tackled by a British team.

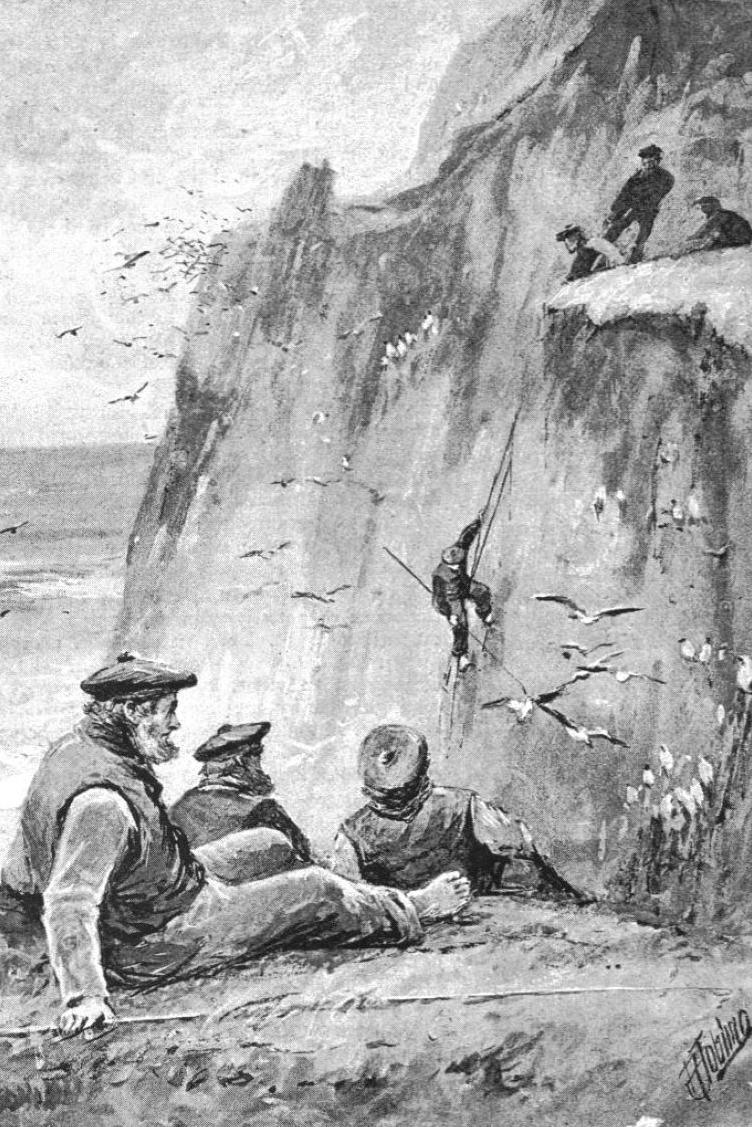

Stac Biorach, a 70m (230ft) sea stack, is nicknamed The Thumb because St Kildans would use their thumbs to help them grip small holds in the rock while negotiating a rocky ledge.

The climb was first documented by Skye-born writer Martin Martin in 1698 after he visited St Kilda and witnessed islanders making the climb as they hunted for seabirds.

The British group, including 33-year-old Robbie Phillips from Edinburgh, are the first people to have completed the climb in 133 years.

Mr Phillips, a professional climber and film-maker, used his thumbs - a technique still a feature of modern climbing for difficult holds - to get himself over the ledge.

The last time Stac Biorach was climbed was in 1890 by Irish naturalist Richard Manliffe Barrington.

St Kilda, a group of small islands and towering columns of rock called sea stacks, lies about 110 miles (177km) west of the Scottish mainland in the North Atlantic.

Robbie Phillips is a professional climber and film-maker who lives in Edinburgh

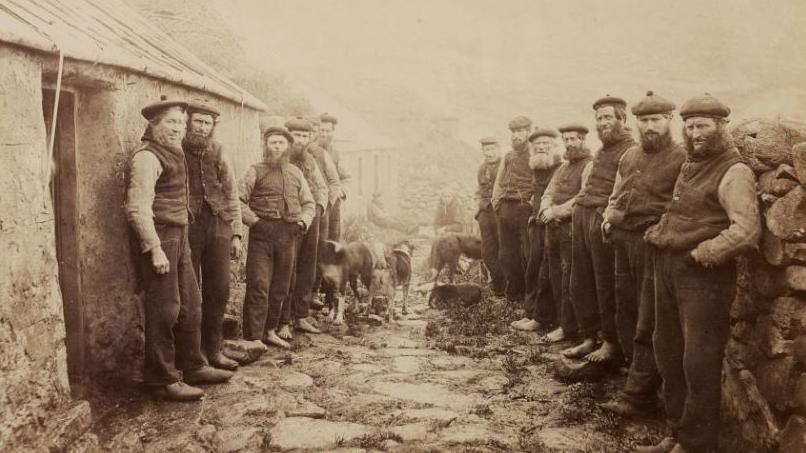

For centuries islanders hunted sea cliffs for birds and their eggs - for food, feathers and oils.

They climbed barefoot and with only horse-hair ropes around their waists to pull them back into boats if they fell.

St Kilda's last inhabitants were evacuated in 1930 after life became unsustainable.

Mr Phillips said: "Climbing The Thumb was like walking in the footsteps, or climbing in the fingerprints of the St Kildans.

"It’s a testament to their bravery and mental fortitude, to climb on to that sea stack 70m (230ft) above the raging Atlantic without even shoes is wild to imagine.

"The St Kildans didn’t just survive out here, they thrived with the skills they honed and the traditions they upheld.”

Robbie Phillips climbing in St Kilda

During September's expedition to St Kilda, the team also made a first ascent of an overhanging sea cliff on the island of Soay, on the westernmost tip of the British Isles.

About a year of planning went into this climb, including a careful study of a photograph of the cliff to help identify a safe route up.

There was a limited timeframe for the feat as it, along with The Thumb ascent, had to be done outside the seabird breeding season and needed calm weather.

National Trust for Scotland, which manages St Kilda as a Unseco World Heritage site, was consulted on the expedition.

Mr Phillips and other members of the team jumped to the sea level base of the cliff from a dinghy and then over several hours free climbed to the summit.

The team made the ascent over about seven pitches, placing equipment called protection - removable metal devices such as wires and cams - into small gaps in the rock which they then attached rope to.

If they fell, the climbers would only drop as far as a piece of protection - and not all the way into the sea.

They reached the summit as the sun went down.

But Mr Phillips said his dream was to return to St Kilda to tackle the same cliff.

During September's first ascent, he had to pull on a piece of gear to help him get up the rockface.

This changed the climb from being classified as a pure free climb to a partially aided one.

"It seems ridiculous to go back to St Kilda and climb the same climb again - but without pulling on a bit of gear. That is the game we play as climbers," he said.

Related topics

- Published9 February 2021

- Published29 August 2020