Article: published on 28 January 2024

- Image source, Ordnance Survey

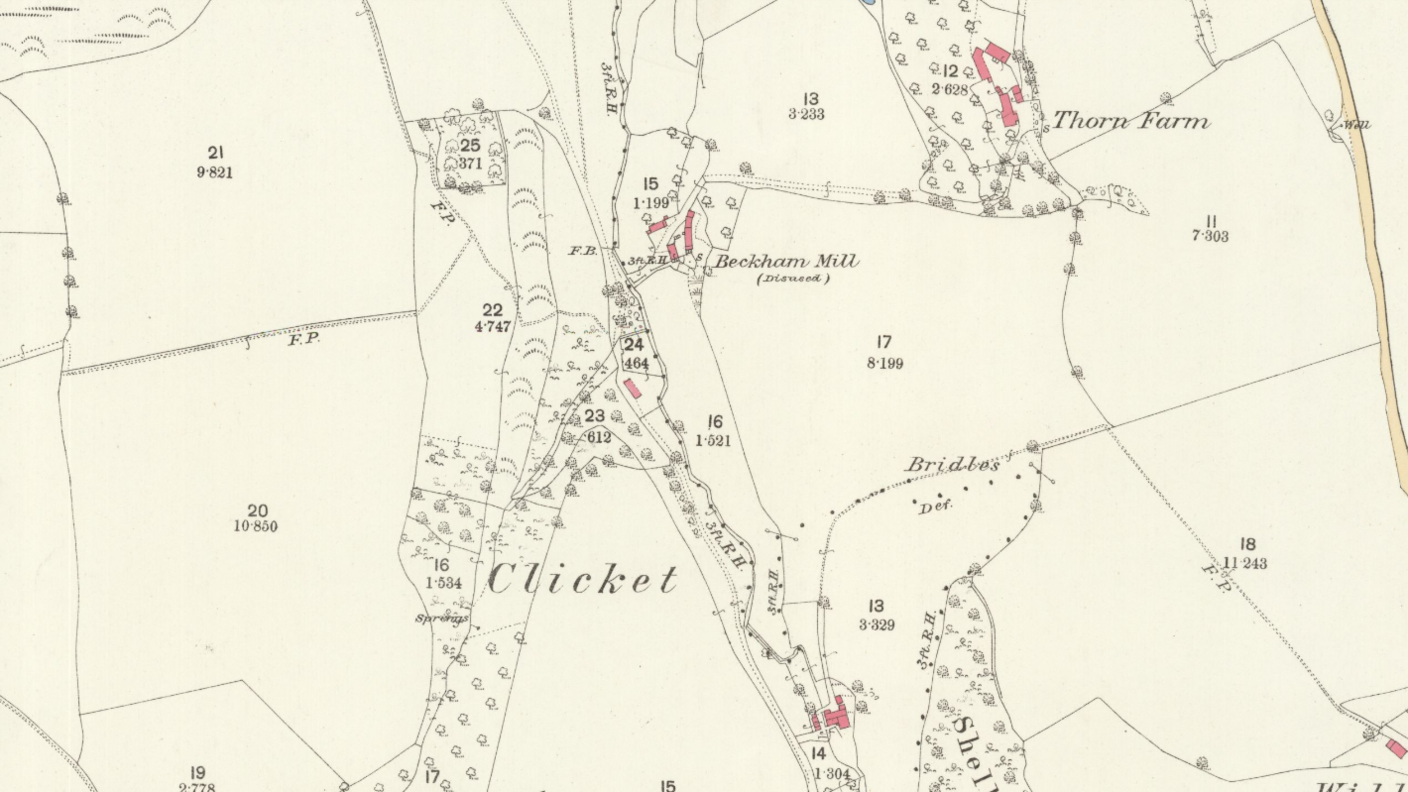

Image caption, You will not find Clicket on Google Maps, but it is signposted and on Ordnance Survey maps

1 of 5

Clicket: The abandoned Somerset village you can still visit

- Published

Hidden at the bottom of a steep-sided valley on Exmoor are the remains of something akin to Somerset's very own lost city.

Mother Nature has stripped back the trees and bushes to reveal the crumbling ruins, making winter the perfect time to visit.

Very little is known about the community and the families that once chose to live in this rural part of Somerset but thanks to the dedication of some local experts, some of Clicket's lost history is rising to the surface.

Early official records for Clicket are almost non-existent, due the area being economically deprived, but a medieval lay subsidy dates one farm building, Thorn Farm and a mill building, back to the 14th Century.

The records then go quiet until the early 1840s when school, tax and church documents can officially place families living in Clicket.

By that point the village, between Timberscombe and Luxborough, had expanded to include other farm buildings, along with a thriving corn mill and various cottages.

Clicket can only be accessed on foot from Timberscombe and Luxborough

Census records in 1881 show there were five families living in the village in Clicket but by 1891 they had all gone.

If you follow the public footpath to the bottom of the valley you will find the ruins of Beckham Corn Mill, which sits next to the River Churnet.

The mill, along with a bakery, a limestone quarry and a farm meant those living in Clicket in the 19th Century could be fully self sufficient.

Life was far from ideal though as Clicket did not have a church, a shop, a Post Office or a school - so children had to walk two miles to the nearest school in Timberscombe.

Access was also a problem, due to the narrow tracks, so the mill workers had to use donkeys to carry goods in and out of the village.

'Clicket became unsustainable'

Marion Jeffrey runs a local history group at St Petrock's Church in Timberscombe.

She said: "This was land which was available. Poor land. Difficult land. Inaccessible land. Away from any other centres.

"So you come here because you have to rather than as a choice.

"One of the biggest reasons why this area was de-populated was the repeal of the corn laws in 1846.

"It allowed mass importation of cheap grain from the United States, from Canada and all over - and the domestic UK market couldn't compete.

"It just made life so intolerable, given the remoteness of the area and with the railways coming in people could go away and find a life that was less stressful."

Marion Jeffrey runs guided walk and talks to Clicket for Exmoor National Park

Ms Jeffrey said the the name Clicket is "very unusual" and no one is entirely sure of its origin.

"In the history books dating to 1327 there is a man called Nicholas Clicket, who lived in Porlock," she said.

"Porlock is only five miles from Clicket so maybe he owned some land here.

"Another story is Clicket is the sound that the mill wheel makes as it rotates and it makes that click-clacking sort of sound.

"But one of the stories I love about Clicket is it once had a female miller, which I've always been thrilled about.

"Ursula Tarr came and settled with her family."

The last residents of Clicket photographed in the 1880s

Ms Jeffrey said she plans to do a guided walk to Clicket in April 2024 on behalf of Exmoor National Park.

In a post on social media the national park said: "Our walks delve into the history of our local villages, towns and landscapes with tales about historic buildings and local characters.

"Regular walks take place between April and October in and around Dunster, Lynmouth, Porlock and Selworthy.

"We also offer walks on an ad-hoc basis for organised groups. For more information you can also ask the staff at our National Park Centres."

If you visit Clicket on your own, many of the ruins have now been fenced off by the current landowner for health and safety reasons, and to stop vandalism.

- Published13 January 2024

- Published2 August 2023

- Published9 April 2023