Lab-grown 'mini-guts' to help Crohn's patients

Arthur's treatment suppresses his immune system and he often only attends school for half days

- Published

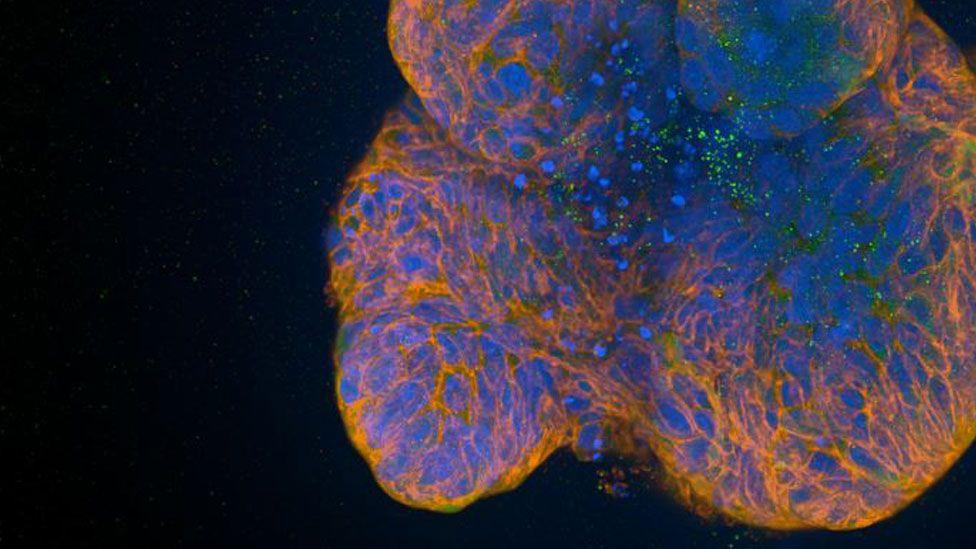

Scientists have grown "mini-guts" in a laboratory to help understand the DNA changes that may play an important role in Crohn's disease.

The University of Cambridge researchers said the mini organs could be used to create the best individualised treatment for sufferers.

One in about 350 people in the UK have this lifelong form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to the university.

Paediatric gastroenterology professor Matthias Zilbauer said cases have been rising worldwide, particularly in young children, "but despite decades of research, no-one knows what causes it".

Children and adolescents donated pieces of their bowel to the study

Arthur, one of the children who took part in the Translational Research in Intestinal Physiology and Pathology study, said: "I think it's quite cool to be part of the study."

Now aged 11, he was nine when he was diagnosed, having been told he had toddler diarrhoea, dietary intolerances and even abdominal migraines.

The condition is characterised by inflammation of the digestive tract.

Symptoms can have a major impact on quality of life and include stomach pain, diarrhoea, weight loss and fatigue, and it can also lead to extensive surgery, inpatient admissions and exposure to toxic drugs.

"There are bad days and there are good days, but eventually you'll find the right medicine," said Arthur.

"Sometimes it can take a really long time, but eventually they'll find the thing that works for you."

Prof Zilbauer said: "The organoids that we've generated are primarily from children and adolescents.

"They've essentially given us pieces of their bowel to help with our research."

Prof Zilbauer is based at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Using the mini-guts, the researchers also found that switches, which modify DNA in gut cells, play an important role in the disease and how it presents in patients.

These switches are attached to DNA that turn genes on and off - or turn their activity up or down - leaving the DNA itself intact, but changing the way a cell functions.

These changes in Crohn's patients correlated with severity of disease.

The researchers also discovered the DNA changes are stable, which may explain why a patient appears to be healed but their inflammation has returned - the drugs are treating the symptoms, not the underlying cause.

The findings could help patients such as Arthur access effective treatment more quickly.

The research was largely supported by the Medical Research Council, in collaboration with the university's Milner Therapeutics Institute.

Follow Cambridgeshire news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published5 June 2024

- Published22 February 2024

- Published13 December 2023