The remarkable story of pioneering female engineer accused of spying

Sheffield's Lady of the Lamp, Monica Maurice, who ran Wolf Safety Lamp Company for nearly 40 years

- Published

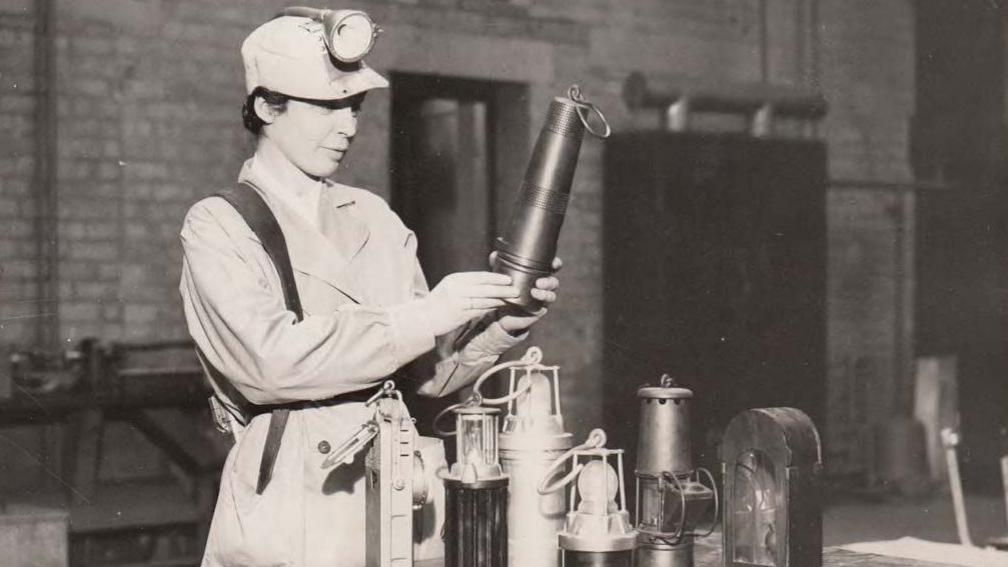

Engineer, pioneer, businesswoman, pilot, mother and rumoured spy - Monica Maurice wore many hats throughout her remarkable life.

For nearly four decades, she ran Wolf Safety Lamp Company in Sheffield and played a key role in making the work of thousands of miners safer with innovative equipment.

Known affectionately as "The Lady of the Lamp" by the coal miners, she was the first - and for 40 years the only - female member of the Association of Mining Electrical Engineers.

As a woman driving change in a heavily male-dominated industry, she earned widespread respect and had a strong reputation, her son John Jackson told the BBC.

"She was like her father, passionate about safety in mines and better working conditions," he said.

"She had that ability to engage with people - ordinary people, not just other engineers but the workforce."

The company, which opened its headquarters in Saxon Road in 1933, produced what was considered one of the best alkaline hand lamps, widely used in mines to illuminate work areas.

"Previously, the flame safety lamp was the only source of light, so the electric lamp was a huge improvement which led to better safety, better output," Mr Jackson said.

The company's site in Heeley, which opened in 1933

Monica's career started in 1930 as secretary to her father William Maurice, before she worked as an engineer apprentice at former parent company Friemann and Wolf in Zwickau, Germany.

Her extensive industry knowledge would later see her participate in a British intelligence mission in Germany, but it resulted in her being wrongly accused of espionage.

"My mother's task was to visit factories that she had been to on a number of occasions, which manufactured items such as batteries, electric light bulbs, miners' lamps," Mr Jackson said.

"The local paper got hold of the story and put out the headline 'lady industrialist from Wolf Safety spying for the country'.

"Rather than industrial secrets or government secrets, it was really just assessing the impact of war damage to German industry."

Monica Maurice had a passion for cars and planes

Away from the factory on Saxon Road in Heeley, Monica regularly indulged in her two passions: cars and aircraft - having qualified as a pilot in early 1935.

An enthusiastic motorist, her son recalled how she would often race up to the airfield in Sherburn in Elmet in North Yorkshire in her Frazer Nash sports car.

"Down to her perceptions of safety, the first thing she did was to put a half-inch thick aluminium plate under the floor where the chains ran from the back of the engine to the rear axle just in case that chain might break," Mr Jackson said.

In 1937, Monica met Arthur Newton Jackson, a Canadian doctor, who she married the following year in a red silk gauze dress, which was considered a bold choice for a wedding.

The garment is now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

John Jackson at the company's site in Saxon Road, Sheffield

The couple settled in Woodhouse, in the south-eastern part of Sheffield, where they raised their three children, who had little knowledge of their mother's accomplishments.

"She was a very modest person, I never remember her bragging about anything," said Mr Jackson.

"In fact, in my younger life, I was totally unaware of all [her] achievements."

Mr Jackson took over the company two years after his mother was awarded an OBE for her outstanding contributions to industrial safety, engineering, and leadership in the mining sector.

Monica Maurice with her husband Dr Arthur Jackson, daughter Willa and son John at Buckingham Palace in 1975

"I worked alongside her for perhaps 30 years. We very often had lunch together, just a sandwich and shared an apple and chatted about things," Mr Jackson said.

"I just wish I'd had a pad and written down every little anecdote that she related but like so many opportunities, you only realise that they were there and missed when it's too late."

On Wednesday, a plaque commemorating her life was unveiled at the company's site.

"In eight years time we will have been here 100 years and I hope to be around to see it," Mr Jackson added.

Listen to highlights from South Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, catch up with the latest episode of Look North.

Who was Sheffield's 'Lady of the Lamp'?

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Yorkshire