Should teen sex be a crime? Indian woman lawyer mounts challenge

Young couples in India often retreat to secluded public spots for moments of intimacy

- Published

In late July, lawyer Indira Jaising mounted a challenge against the legal age for having sex in India - which is 18 years - in the Supreme Court, renewing conversations around the criminalisation of teen sex.

Ms Jaising argued that consensual sex between 16 and 18-year-olds is neither exploitative nor abusive and urged the court to exempt it from criminal prosecution.

"The purpose of age-based laws is to prevent abuse, not to criminalise consensual, age-appropriate intimacy," Ms Jaising has said in her written submissions to the court.

But the federal government has opposed this, saying that introducing such an exemption would jeopardise the safety and protection of children (persons under the age of 18, according to Indian laws), opening them up to abuse and exploitation.

The case has re-ignited debate around consent and whether Indian laws, especially the country's main law against child sexual abuse - Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 or Pocso - should be altered to introduce a provision exempting 16 to 18 year-olds having consensual sex from their ambit.

Child rights activists say exempting teens protects their autonomy, while opponents warn it could fuel crimes like trafficking and child marriage.

Experts question whether teens can bear the burden of proof if abused. More importantly, who decides the age of consent laws - and whose interests do they truly serve?

Like many countries, India has struggled to set its age of sexual consent. Unlike the US, where it varies by state, India enforces a uniform age nationwide.

India's legal age for having sex is also much higher than most European countries, or places like UK and Canada, where it is 16.

It was 10 years when India's criminal code was enacted in 1860 and was increased to 16 in 1940 when the code was amended.

Pocso introduced the next major change, pushing the "age of consent" to 18 years in 2012. A year later, India's criminal laws were amended to reflect this change and the country's new criminal code, introduced in 2024, has adhered to this revised age.

But over the past decade or so, many child rights activists and even courts have taken a critical view of the country's legal age to have sex and have called for it to be lowered to 16 years.

They say the law criminalises consensual teen relationships and is often misused by adults to control or block relationships - especially those of girls.

Sex remains a taboo topic in the country even though studies have shown that millions of Indian teenagers are sexually active.

"As a society, we're also divided along caste, class and religious lines, which makes the [age of consent] law even more susceptible to misuse," says Sharmila Raje, co-founder of Foundation for Child Protection-Muskaan, a non-profit working to prevent child sexual abuse for over two decades.

Many schools in India do not have sex education as part of the curriculum

In 2022, the Karnataka High court directed India's Law Commission - an executive panel that advices the government on legal reform - to rethink the age of consent, external under Pocso, "so as to take into consideration the ground realities".

It noted several cases where girls over 16 fell in love, eloped, and had sex, only for the boy to be charged with rape and abduction under Pocso and criminal law.

In its report the following year, the Law Commission ruled out lowering the age of consent, but recommended "guided judicial discretion", external during sentencing in cases involving "tacit approval" from children aged 16 to 18 years, meaning where the relationship has been consensual.

Though this is yet to be implemented, courts across the country have been using this principle to allow for appeals, grant bail, make acquittals and even quash cases after taking into consideration the facts of the case and the victim's testimony.

Many child rights activists, including Ms Raje, urge this provision be codified to standardise enforcement; left as a suggestion, courts may ignore it.

In April, the Madras High Court overturned the acquittal in a case where the 17-year-old victim was in a relationship with the 23-year-old accused and the two eloped after the victim's parents arranged her marriage to another man. The accused was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

"The court adopted a literal interpretation of the Pocso Act," Shruthi Ramakrishnan, a researcher at Enfold Proactive Health Trust - a child rights charity - noted in her column, external in The Indian Express newspaper, calling it a "grave miscarriage of justice".

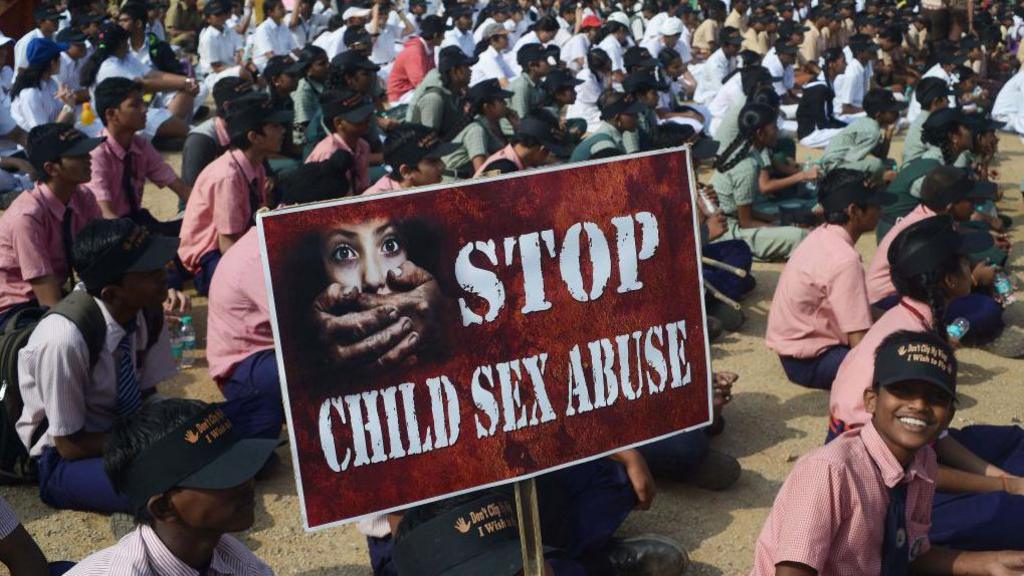

The Pocso Act was introduced to protect children against all forms of sexual abuse

Ms Jaising argues that judicial discretion at sentencing isn't enough, as the accused still faces lengthy investigations and trials.

India's judicial system is infamously slow with millions of cases pending across all court levels. A research paper by India Child Protection Fund found that as of January 2023, external, nearly 250,000 Pocso cases were pending in special courts set up to try these cases.

"The process is the punishment for many," Ms Jaising notes.

"A case-by-case approach leaving it to the discretion of judges is also not the best solution as it can result in uneven results and does not take into account the possibility of bias," she adds.

She urges the court to add a "close-in-age exception" for consensual sex between 16- and 18-year-olds in Pocso and related laws. This "close-in-age exception" would prevent consensual acts between peers in that age group from being treated as crimes.

Lawyer and child rights activist Bhuwan Ribhu warns that a blanket exception could be misused in cases of kidnapping, trafficking, and child marriage. He advocates judicial discretion paired with a justice system overhaul.

"We need faster processes so that cases are disposed off in a time-bound manner. We also need better rehabilitation facilities and compensation for victims," he says.

Enakshi Ganguly, co-founder of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, however, agrees with Ms Jaising.

"We can't shy away from making changes because we're afraid of the law being misused," she says, adding that Ms Jaising's argument is not new as over the years, many activists and experts have made similar recommendations.

"Laws need to keep pace with changes in society if they are to remain effective and relevant," she says.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, external, YouTube, external, Twitter, external and Facebook, external.