Manhunt in Australian bush brings long-dismissed conspiracy theorists to the fore

A huge search is under way in Australia for a heavily armed fugitive who allegedly shot two police officers

- Published

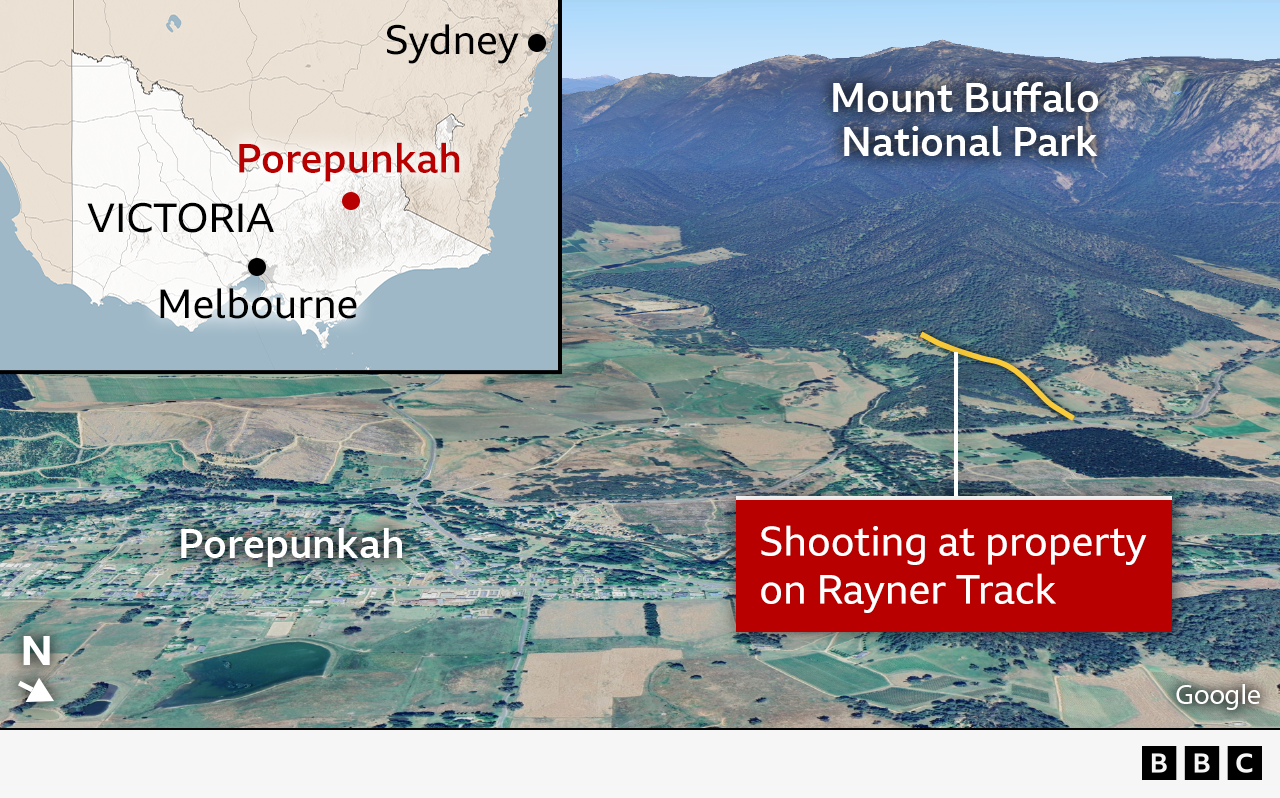

Even in Australia, Porepunkah is a town few would have heard of before this week. Fewer still could pronounce it.

Nestled at the base of densely wooded mountains in the Australian Alps, it is home to about 1,000 people and beloved for its wineries, bushwalking, and a peaceful atmosphere - something that has now been shattered.

Choppers whir overhead. Kevlar-clad officers methodically patrol the town. Armoured vehicles roll down its streets. Porepunkah is now the centre of a massive manhunt for a heavily armed man that police allege murdered two of their own in cold blood.

Officers went to Dezi Freeman's property on the outskirts of the rural Victorian town on Tuesday, with a warrant to search it. They were met with gunfire, before their alleged attacker – a "sovereign citizen" with a well-documented hatred of authority – vanished into nearby bushland.

The shooting – which appears hauntingly similar to an ambush of police in Queensland three years ago – has shocked the town and revived questions over how the country deals with growing sects of anti-government conspiracy theorists.

"This is exactly the sort of thing that we've been fearing," says Joe McIntyre, who has spent years studying these groups in Australia.

Small community 'rattled'

Police were clearly expecting that this wasn't going to be a straightforward interaction. A detailed risk assessment had been conducted and 10 officers – a show of force – were tasked with executing the search warrant, reportedly relating to a sex crimes investigation.

Among them was a local detective from a nearby town who was on the brink of retirement. Neal Thompson was selected for the job because he'd had previous dealings with the target and was thought to have built rapport with him, The Age newspaper reported.

Within minutes of arriving at the property, he was shot dead, alongside Senior Constable Vadim De Waart. Another unnamed officer was gravely injured and is recovering in hospital.

Senior Constable Vadim De Waart and Detective Neal Thompson have been named as the officers killed

Mr Freeman escaped into thick tree cover on his property with several firearms, including, according to local media, an illegal homemade gun and at least one weapon stolen from the slain officers. He remains on the run.

Horror quickly echoed around the valley.

Holed up in the caravan park her family owns, Emily White's voice choked up as she explained her fear and surprise.

"I got a knock on my door from one of our workers saying that there's an active shooter. I said, 'What? You're lying, you're joking'," she told the BBC over the phone on Tuesday night.

"We're such a small community, and we'll leave our cars unlocked, and we'll leave our front doors open. Nothing like this ever happens."

Residents say it's the kind of town where everyone knows everyone. So it didn't take long for Mr Freeman – legally known as Desmond Filby – to be fingered as the alleged culprit.

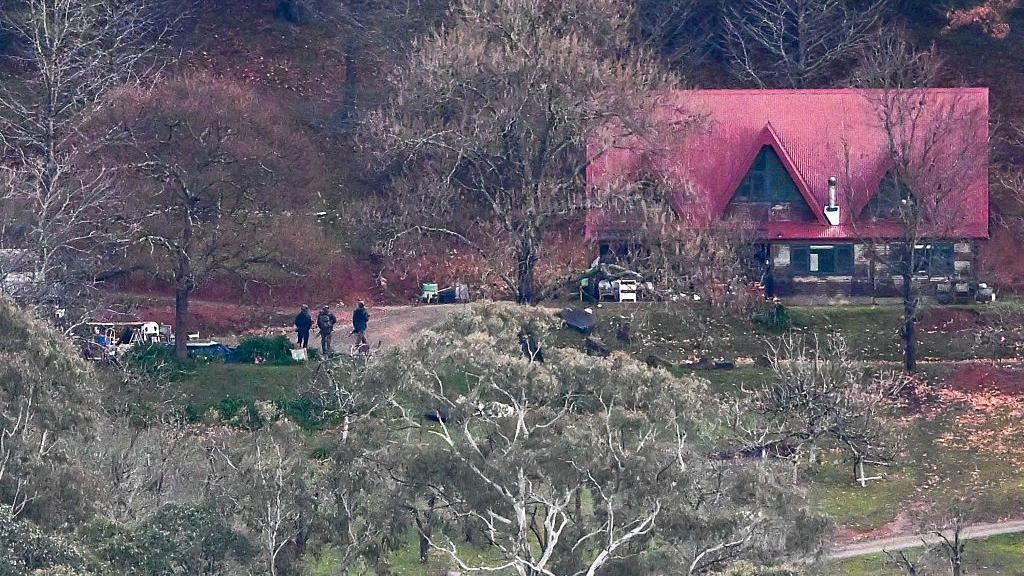

Armed police have descended on the remote area to hunt the suspect down

Mark Simpson, who manages the local airfield, told the BBC he'd seen the 56-year-old around town and said g'day a handful of times, but had no inkling of his beliefs.

"The only sovereign citizen I've heard of years ago was a guy in Western Australia… He had his own stamps and money," he says.

Misty-Rose, who runs a business in town and didn't want to give a last name, says there has long been a cluster living in the Porepunkah community – and many in town knew Mr Freeman was one of them.

Dezi Freeman gave an interview to A Current Affair in 2018 complaining about his neighbours

Sovereign citizens are a type of anti-authoritarian conspiracists loosely dubbed pseudo-law believers: people who reject established government and law as illegitimate, justified by legal-sounding arguments that have no actual basis.

In practice, that can mean anything from refusing to register a car and hold a driver's licence, to - in the case of Mr Freeman - trying to use their own asserted authority to arrest a magistrate in court.

Though Mr Freeman and his family seemed to be well integrated in the community, Misty-Rose says, he was also the subject of town whispers.

He was rumoured to live inside a bus parked on his block of land, and his arrest outside a courthouse in nearby Myrtleford several years ago – where he was protesting after his treason case against the state's leader failed – had sparked chatter.

But these tales were no reason to suggest one day he would be the subject of a manhunt that's caught global attention, and the community is "rattled", Misty-Rose says.

"It's freaking scary," Ms White agrees. "These police officers went to work… just to check on someone, and now they're not coming home."

Like many Australians - even the prime minister, Anthony Albanese - she says the circumstances feel upsettingly similar to the Wieambilla shooting in Queensland three years ago.

"Is this really happening again?" Ms White asked.

In 2022, two young officers were shot and killed after travelling to a rural property to check on a person who had been reported missing. Another police officer was injured and a fourth hunted through the bush for hours before she was rescued.

The Queensland offenders - two brothers and a woman who was at different times married to both of them - were people who were known to hold extreme anti-government, pseudo-law beliefs.

Grief and questions after shoot-out shocks Australia

- Published14 December 2022

US arrests man over Australian terror attack

- Published6 December 2023

The families of two officers who died, Rachel McCrow and Matthew Arnold, have said their murders were preventable and begged authorities to learn from the tragedy that ripped apart their families.

"The time for excuses is over… Matt and Rachel's deaths must not be in vain," Sue Arnold said after an inquest, which is yet to deliver its findings.

The night of the Porepunkah shooting, Victoria Police Commissioner Mike Bush was repeatedly asked what authorities had learned in the years following the Queensland incident: "Has anything changed since?"

He said he couldn't comment, citing the early stage of the investigation and reiterating that police were focused first on finding Mr Freeman.

'Not just one or two crackpots'

Pseudo-law believers are not new in Australia, or unique to it. Large sects of these people exist in the US, and similarly have been documented in Australia since the 70s.

In the US, which has seen many incidents of violence from sovereign citizens, the FBI has for at least 15 years seen them as a domestic terrorism threat.

But in Australia they've long been treated as a bit of a joke - at worst, an annoyance.

That perception shifted as Australia confronted the pandemic and implemented some of the world's strictest Covid-19 rules. Unprecedented government intervention - everything from lockdowns to vaccination mandates – further fuelled growing mistrust in authorities, proving a massive boost to anti-authoritarianist ranks and a trigger for increasing fervour amongst them.

Porepunkah locals say this was true of Mr Freeman.

In Mr Freeman's home state of Victoria, protestors regularly demonstrated against Covid-19 restrictions

Online, self-declared "gurus" seized on this energy, preaching their pseudo-law beliefs and selling guides, even scripts, on how to use them to outsmart Australian authorities, driving the spread of the ideas further and frustrating already overwhelmed legal and policing systems while lining their pockets.

It's hard to estimate just how many Australians now dabble in this kind of ideology, but experts say it could be up to tens of thousands. It's believed many are attracted to rural or regional parts of the country, seeking out the margins of society, away from the institutions and authorities they reject.

Dr McIntyre, an associate professor of law, says their belief system has a "dangerous underpinning".

"Once you start chopping and choosing which laws you're going to obey… you're starting to really abandon those core ideas that a democracy is built on.

"It's not many steps further to say, 'Why should I obey norms about violence or norms about gun ownership', or any of these things."

Tributes have flowed from around Australia for the officers killed

Journalist Cam Wilson, who has spent years investigating sovereign citizens for his book Conspiracy Nation, says most pseudo-law adherents never resort to violence.

"But the fact that there is this loose grouping of people who are primed to believe that any government interaction is fundamentally a kind of violence towards them… this creates the conditions for someone to respond in really extreme ways.

"From a distance, it's hard to know which of them are just people talking… and which are those willing to actually carry out some of the violence they often speak about."

Authorities in Australia say they're taking the threat of pseudo-law conspiracy theorists seriously.

In a 2023 briefing note, released under freedom of information laws, the Australian Federal Police acknowledged that "while these groups present and behave very differently to other extremist groups, there is an underlying capacity to inspire violence".

Australia's intelligence services are similarly cognisant of the danger they pose, the prime minister said on Tuesday night.

One of the houses on the Porepunkah property where the shooting unfolded

But Dr McIntyre argues there needs to be more urgency put into understanding these conspiracy theorists and reining them in.

"It is a very fragmented movement, a social phenomenon, more than an organisation.

"[But] this is not just one or two crackpots, and the tools that we have to deal with this aren't particularly well adapted to this type of behaviour.

"We need more of a whole of government approach that looks at integrating information-sharing, that looks at developing appropriate safeguards, that looks at cutting off the head of the Hydra," he says referring to the "gurus" that sell pseudo-law bibles.

Mr Wilson is unsure if harsher policing or surveillance will make a difference. "I worry that cracking down on pseudo-law adherents could backfire and further entrench their irrational beliefs. Rather than being a deterrent, anti-government conspiracy theories prime people to view legal consequences as unfair persecution that feeds their resentment."

He says gun control, already strict in Australia but increasingly ill-enforced, is another area to look at.

But, ultimately, both he and Dr McIntyre say the root causes - many of which are problems that have troubled Australian authorities for decades – need to be addressed. They include poor education, particularly when it comes to the legal system, and limited mental health and social support for vulnerable people.

"This is a threat in Australia, as long as we have conditions that lead people to believe these kinds of ideas, to believe that the world is unfair… [and] their only solution is to act violently," Mr Wilson says.

Related topics

- Published27 August

- Published27 August