What we know about the South Korea plane crash

Watch: At the scene of the South Korea plane crash investigation

- Published

Nearly 180 people died after a plane crashed as it was landing in South Korea on the morning of Sunday 29 December.

Harrowing video footage shows the Jeju Air plane coming off the runway before colliding with a barrier and bursting into flames at Muan International Airport.

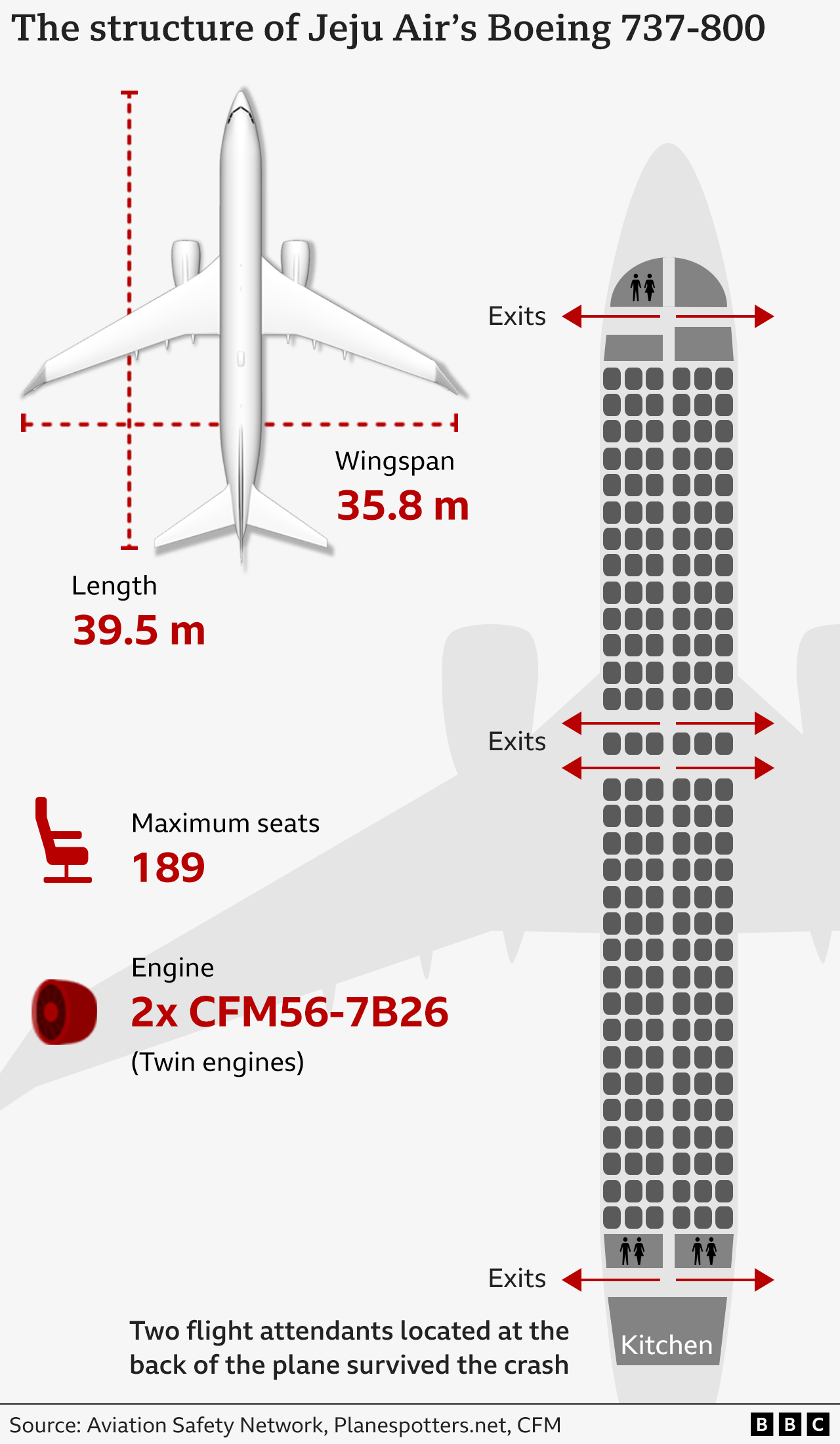

The plane, which was returning from Bangkok, Thailand, was carrying 181 people - 179 of whom were killed. Two crew members were rescued from the wreckage.

Authorities are investigating the cause of the crash, with fire officials indicating a bird strike and bad weather. However experts have warned the crash could have been caused by a number of factors.

What happened?

Flight 7C2216 was a Boeing 737-800 operated by Jeju Air, Korea's most popular budget airline.

Air traffic control authorised the plane to land at Muan International Airport at about 08:54 (23:54 GMT) - just three minutes before issuing a warning about bird activity in the area.

At 08:59, the pilot reported that the plane had struck a bird, declaring "mayday mayday mayday" and "bird strike, bird strike, go-around". The pilot then aborted the original landing and requested permission to land from the opposite direction.

Air traffic control authorised the alternative landing at 09:01 - and at 09:02 the plane made contact with the ground, coming down at roughly the halfway point of the 2,800m runway.

One video appears to show the plane touching down without using its wheels or any other landing gear. It skidded down the runway, overshot it and crashed into a concrete wall, before erupting into flames.

A witness told the South Korean news agency Yonhap they had heard a "loud bang" followed by a "series of explosions".

Videos from the scene show the plane ablaze with smoke billowing into the sky. The first of two survivors was rescued from the crash at about 09:23, with the second being rescued from inside the tail section of the plane at about 09:50.

Could a bird strike have contributed to the crash?

Lee Jeong-hyun, chief of the Muan fire department, told a televised briefing that a bird strike and bad weather might have caused the crash - but that the exact cause was still being investigated.

The flight and voice recorders from the plane were recovered, though reports say that the former was damaged and that data from the devices could take up to a month to decode.

One passenger on the flight messaged a relative, saying that a bird had been "stuck in the wing" and that the plane could not land, local media reported.

Officials, however, have not confirmed whether the plane did actually collide with any birds.

The head of Jeju Air's management said that the crash was not due to "any maintenance issues".

The South Korean transport department said that the head pilot on the flight had held the role since 2019 and had more than 6,800 hours of flight experience.

Geoffrey Thomas, an aviation expert and editor of Airline News, told the BBC that South Korea and its airlines were considered "industry best practice" and that both the aircraft and the airline had an "excellent safety record".

Mr Thomas separately told Reuters news agency that he was sceptical that a bird strike alone could have caused the crash.

"A bird strike is not unusual. Problems with an undercarriage are not unusual. Bird strikes happen far more often, but typically they don't cause the loss of an airplane by themselves," he said.

BBC reports from site of South Korea's deadliest plane crash

Who are the plane crash victims and survivors?

The plane was carrying 175 passengers and six crew. Two of the passengers were Thai and the rest are believed to have been South Korean, authorities have said. Many are thought to have been returning from a Christmas holiday in Thailand.

The official death toll stands at 179 - making it the deadliest plane crash on South Korean soil.

All the passengers and four members of crew died.

Authorities have so far identified 174 bodies and are still checking the remaining five "due to DNA inconsistencies", according to Yonhap, external.

Officials have been collecting saliva samples from family members gathered at Muan Airport to help identify bodies of victims. Other victims have been identified by their fingerprints.

Five of the people who died were children under the age of 10. The youngest passenger was a three-year-old boy and the oldest was 78, authorities said, citing the passenger manifest.

"I can't believe the entire family has just disappeared," Maeng Gi-Su, 78, whose nephew and grand-nephews were on the flight, told the BBC. "My heart aches so much."

South Korea's National Fire Agency said two members of the flight crew - a man and a woman - had survived the crash.

The man has woken up and is "fully able to communicate", according to Yonhap, which cites the director of the Seoul hospital where he is being treated.

More than 1,500 emergency personnel have been deployed as part of recovery efforts, including 490 fire employees and 455 police officers. They have been searching the area around the runway for parts of the plane and those who were onboard.

Emergency workers have been searching around the runway for parts of the plane

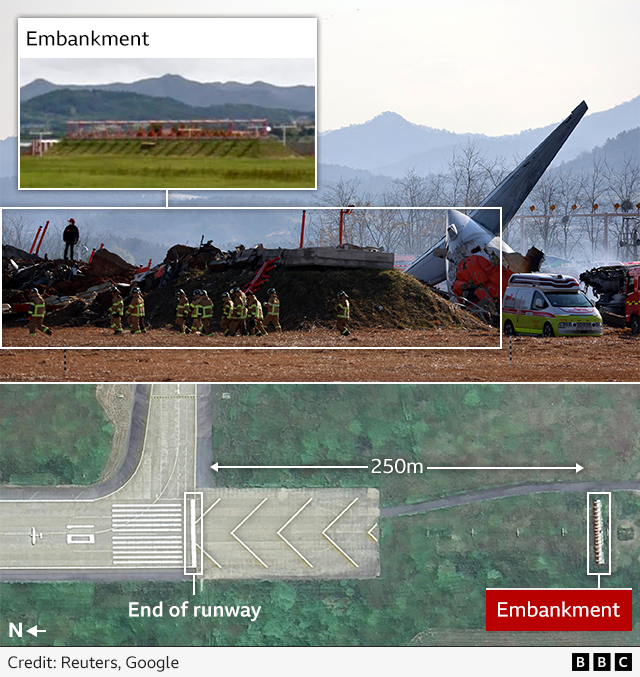

Why was there a concrete wall at the end of the runway?

Aviation experts have raised questions about an "unusual" concrete wall near the runway and its role in the crash.

Footage shows the plane coming off the runway before colliding with the wall and bursting into flames.

Air safety expert David Learmount said that, had the "obstruction" not been there, the plane "would have come to rest with most - possibly all - those on board still alive".

"Unfortunately, that thing was the reason that everybody got killed, because they literally hit a concrete structure," Captain Ross Aimer, the chief executive of Aero Consulting Experts, told Reuters news agency. "It shouldn't have been there."

Aviation analyst Sally Gethin questioned whether the pilot knew the barrier was there, particularly given the plane was approaching from the opposite direction from the usual landing approach.

The concrete structure holds a navigation system that assists aircraft landings - known as a localiser - according to Yonhap.

At 4m high, it is covered with dirt and was raised to keep the localiser level with the runway to ensure it functions properly, Yonhap reported.

South Korea's transport ministry has said that other airports in the country and some overseas have the equipment installed with concrete structures. However officials will examine whether it should have been made with lighter materials that would break more easily upon impact.

South Korean officials have said the structure was about 250m (820ft) from the end of the runway and most airports in the country follow international rules recommending a safety area of 240m (787ft).

However, remarks in the airport's operating manual, uploaded early in 2024, said the embankment was too close to the end of the runway and recommended that the location of the equipment be reviewed during a planned expansion.

Former pilot John Cox, chief executive of Safety Operating Systems, told Reuters the runway design "absolutely (did) not" meet industry best practices, which preclude any hard structure within at least 300m (984ft) of the end of the runway.

South Korea's director-general for airport policy, Kim Hong-rak, said the government would "review the relevant regulations and their application".

At a news conference on Tuesday, Jeju Air's chief executive Kim Yi-bae appeared to sidestep a question about the wall.

Asked by a reporter if he thought the wall was a factor in the disaster, he did not give a direct answer and instead said it was right to call the plane crash the Jeju Air disaster, rather than the Muan Air disaster.

What has the airline said?

Speaking on Tuesday, Jeju Air's chief executive said the airline would reduce its air traffic this winter by 10-15% to carry out more maintenance work.

But Kim Yi-bae said this was not an admission that the company was running too many planes.

No issues were brought to light when the plane was inspected on the day of the crash - and the airline was monitoring the weather both before and after the flight, he added.

Mr Kim said a different Jeju flight faced issues with its landing gear on Monday and was forced to return to Seoul's international airport but it has been declared safe.

He said the pilot had spotted that casing to access the landing gear was slightly open and reported this, with the plane returning to the airport for maintenance.

The plane had also been a Boeing 737-800, the same model as the aircraft that crashed on Sunday.

In his news conference, Mr Kim said Jeju Air had paid the most fines and faced the most administrative action of any Korean airline over the last five years. But he insisted the airline has consistently improved its safety record.

He said the company had a strict maintenance checklist, adding: "If something was missed it would be a grave problem."

Jeju Air has apologised to the victims' families and vowed to provide emergency compensation and cover funeral costs.

The company's chief executive said the airline had no history of accidents and it is believed Sunday's crash has been its only fatal accident since it was launched in 2005.

What are officials doing now?

South Korea's Acting President Choi Sang-mok has ordered an emergency safety inspection of the country's entire airline operations, which is set to be completed by 3 January.

Muan has also been declared a special disaster zone, which makes central government funding available to the local government and victims.

All flights to and from Muan International Airport have been cancelled, with the airport staying closed until 7 January.

A "black box" flight data recorder recovered from the crash site was missing a key connector and authorities were reviewing how to extract its data. However retrieval of data from the cockpit voice recorder has begun, South Korea's transport ministry said.

A national seven-day period of mourning has been declared, and New Year's Day celebrations in the country are likely to be cancelled or scaled down.

Aircraft maker Boeing has said it is in touch with Jeju Air and stands "ready to support them".

What is a bird strike?

A bird strike is a collision between a plane in flight and a bird. They are very common - in the UK, there were more than 1,400 bird strikes reported in 2022, only about 100 of which affected the plane, according to data from the Civil Aviation Authority, external.

The best known bird strike occurred in 2009, when an Airbus plane made an emergency landing on New York's Hudson River after colliding with a flock of geese. All 155 passengers and crew survived.

Professor Doug Drury, who teaches aviation at CQUniversity Australia, wrote in an article for The Conversation, external this summer that Boeing planes - like Airbus and Embraer - had turbofan engines, which could be severely damaged in a bird strike.

He said that pilots were trained to be especially vigilant during the early morning or at sunset, when birds were most active.

But some aviation experts are sceptical about whether a bird strike could have caused the crash at Muan Airport.

"Typically they [bird strikes] don't cause the loss of an airplane by themselves," Mr Thomas told Reuters.

Australian airline safety expert Geoffrey Dell also told the news agency: "I've never seen a bird strike prevent the landing gear from being extended."

Related topics

- Published29 December 2024

- Published29 December 2024