Lives at risk over inaction on prisons says report

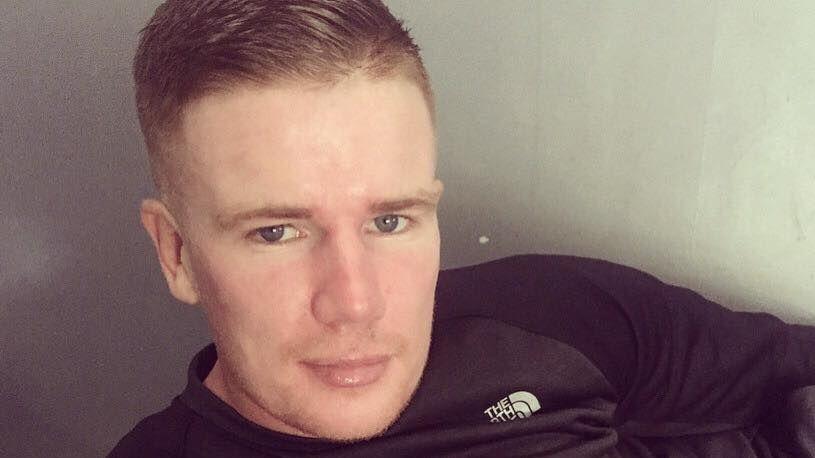

Conor McHugh is one of at least 346 people to have died in Scottish prisons in the past decade

- Published

The lives of Scottish prisoners are at risk because of decades of inaction by the Scottish government, according to a new report.

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) criticises the “glacial pace of change” in tackling overcrowding, suicides and mental health problems in prisons.

It says recommendations made 30 years ago still have not been implemented despite ministers agreeing to them.

The Scottish government said it had already taken significant action but recognised there was more to do.

'No longer acceptable'

At least 346 people have died in Scottish prisons in the past decade, with suicide and drugs deaths on the rise.

The SHRC report highlights decades of failures to reduce suicides and end the use of segregation for people struggling with their mental health.

It says there is no mandatory mental health training for prison staff and people in need of psychiatric care are not being transferred from prison to hospital.

Report author Cathy Asante said lives were at risk

The report's author Cathy Asante told the BBC: “We are talking about lives being at risk and people suffering such a level of distress that it might be considered ill treatment.

"These are very concerning issues."

The SHRC is an independent public body with the power to recommend changes to law, policy and practice in Scottish public authorities.

However, its report found 83% of recommendations by human rights bodies had yet to be implemented in Scotland, with little or no meaningful progress over the last decade.

It said: “The sheer volume of inaction and delay is no longer acceptable."

Watch now: Prisons On The Brink is available here on BBC iplayer.

Lucy Adams investigates the impact of overcrowding, drugs and suicides on inmates and staff, and asks whether our crumbling prison estate can cope much longer.

Conor McHugh is one of hundreds of inmates who have died in Scottish prisons.

He was sent to Kilmarnock prison in May 2020 for eight months for a breach of the peace.

The 29-year-old asked for help with his mental health but was told he could not get an appointment with a mental health nurse until August.

Conor McHugh was sent to Kilmarnock prison in May 2020

He tried to take his own life in July and was taken to hospital but he still did not get to see a psychiatrist.

When he finally got his mental health assessment, three months after he asked for help, he was told he could have drug-induced psychosis but he wasn’t given any medication or treatment at that point.

After a second attempt to take his own life, he was put on suicide watch but within days he was moved back to a normal cell and and his checks were reduced from every 15 minutes to every 30 minutes.

He took his life the following day - two days before he was due to be released.

An internal NHS investigation, seen by the BBC, found mistakes were made.

Conor's mother Gail Donaghy says her son was clearly unwell

Conor had been in prison on short sentences before, but his mother says this time was different because he was clearly unwell.

“The process in jail is, if you are struggling with your mental health you have to ask for help yourself,” Gail Donaghy says.

“Conor did that - he realised he was struggling. He asked for help."

His mother says her son was a prisoner who had committed offences but he was still a human being.

"How could you possibly treat anybody like that?,” she says. “They did not respect his right to life.”

“No mother should have to go and choose a coffin for their own child," Ms Donaghy says.

"Devastating isn’t a big enough word.”

Serco, the private company that ran Kilmarnock prison at the time, said it could not comment on the case because the fatal accident inquiry has not yet been held.

East Ayrshire Health and Social Care Partnership, which was responsible for Conor's healthcare, said: “Every suicide is a tragedy, and our thoughts and sympathies are with the families and friends of all those touched by suicide.

“We have a duty to protect patient confidentiality, and so are unable to provide any further information at this time.”

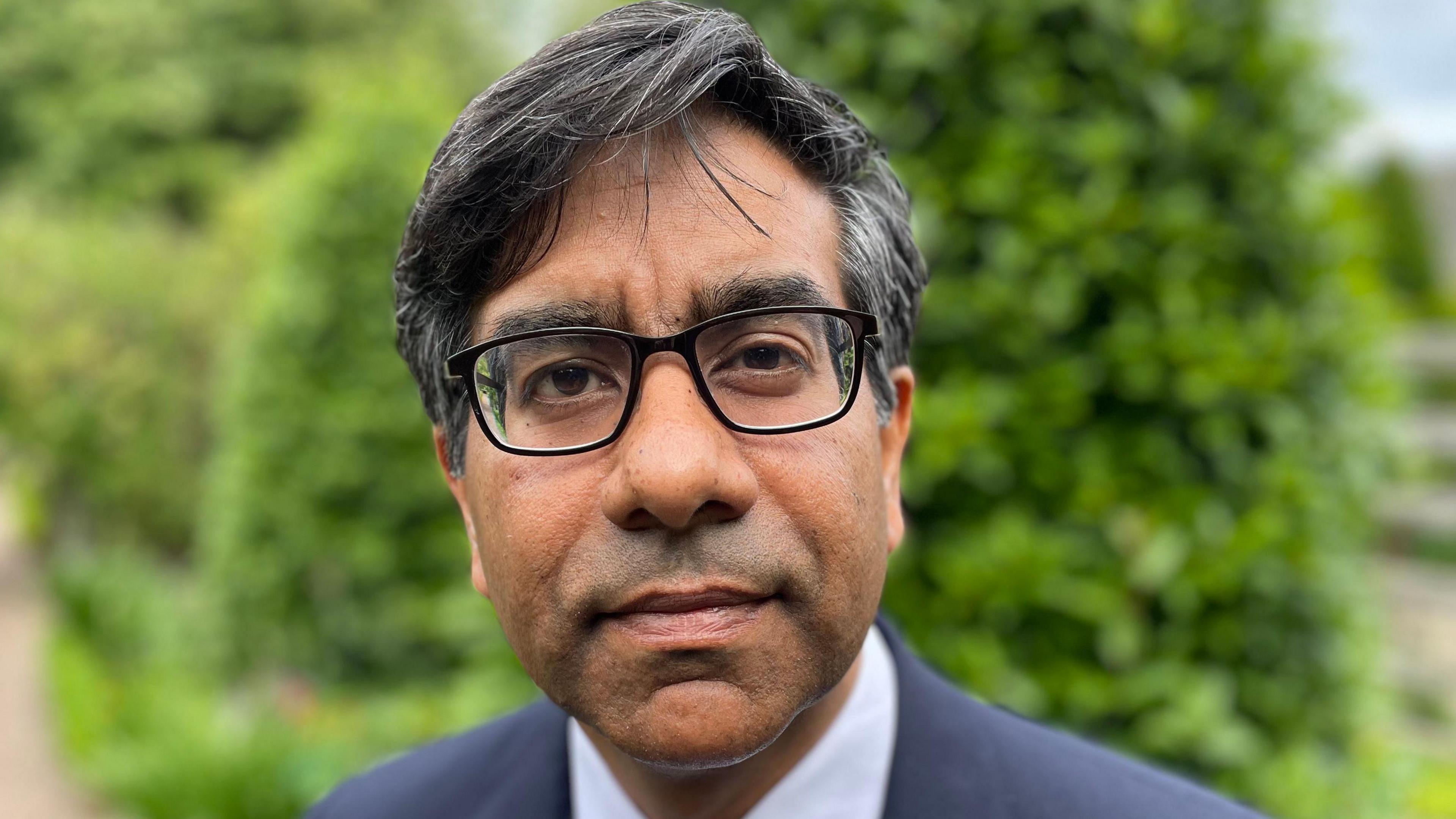

Arun Chopra said he had seen people who were “floridly psychotic” placed in segregation

Arun Chopra, a consultant psychiatrist and medical director of the Mental Welfare Commission, told the BBC he had been on prison visits where he had seen people who were “floridly psychotic” who had been placed in segregation rather than hospital.

He said there needed to be a statutory duty on prisons to record how many people each prison had who were psychotic and in need of a transfer to hospital.

“We saw one person who had been in a segregation unit for 45 weeks and they had been referred for a mental health bed at least 14 weeks prior to us seeing them,” he said.

“I am aware of at least four other cases where the commission has had to work with SPS and the NHS to get people into beds.”

He said if you are having to get the intervention of the watchdog that means “there is a failure of process”.

Kellyanne McNaughton stabbed Michele Rutherford to death at her supported accommodation in Stirling

The report also highlights the failure to create a specialised high-secure psychiatric unit for women in Scotland – despite ministers agreeing to this three years ago.

The family of Michele Rutherford, a care worker stabbed to death last year have called for ministers to take immediate action on this.

Kellyanne McNaughton killed Ms Rutherford at her supported accommodation in Stirling after numerous failed attempts to get her psychiatric help.

The State Hospital at Carstairs is currently all-male so a small number of women detained with specialist mental healthcare needs have been sent hundreds of miles to Rampton high-security hospital in England.

A review commissioned by the Scottish government called the practice “indefensible” and called for women to be admitted to Carstairs.

The review’s author, Derek Barron, said this should happen within nine months of his report’s publication in February 2021. The SHRC report that this needs to be addressed urgently.

Complex issues

A Scottish government spokesperson said the report highlighted work it had done to upgrade the female prison estate, tackle substance use and improve staffing but there was more to do.

“These are complex and wide ranging issues and we are taking action, including bringing forward measures to improve the use of restraint on children in detention, implementing the recommendations of the Independent Review of the Response to Deaths in Prison Custody and work to improve female mental health care,” the spokesperson said.

Justice Secretary Angela Constance told BBC Radio’s Good Morning Scotland: “Action is needed and we are indeed taking action.”

She pointed to "crucial" measures taken by the government in the past year, including an act designed to cut reoffending, children's care and justice reforms, external, releasing prisoners early to reduce the prison population and incorporating a UN charter on children's rights into law.

A Scottish Prison Service spokesperson said it had made progress already in several of the areas covered by the report.

“The first stage of our review of the Talk to Me, suicide prevention strategy has been completed, and we have introduced further measures to keep people safe, including dedicated phonelines, which families can call to raise a concern about a loved one in custody,” they said.

Related topics

- Published5 February 2024