Why does evolution keep creating 'imposter crabs'?

Memes about 'rejecting humanity and becoming a crab' emerged from the fact that evolution keeps turning animals into crab-like creatures

- Published

Viral social media memes being shared by millions of users gleefully declare that humanity's final evolutionary destination is not robots nor extinction - but crabs.

Experts at Crab Museum in Margate say they now have people come in "every day" questioning if humans really will end up sprouting claws.

Ned Suesat-Williams, director of the museum, told BBC Sounds he had never been able to give visitors a "satisfactory" answer.

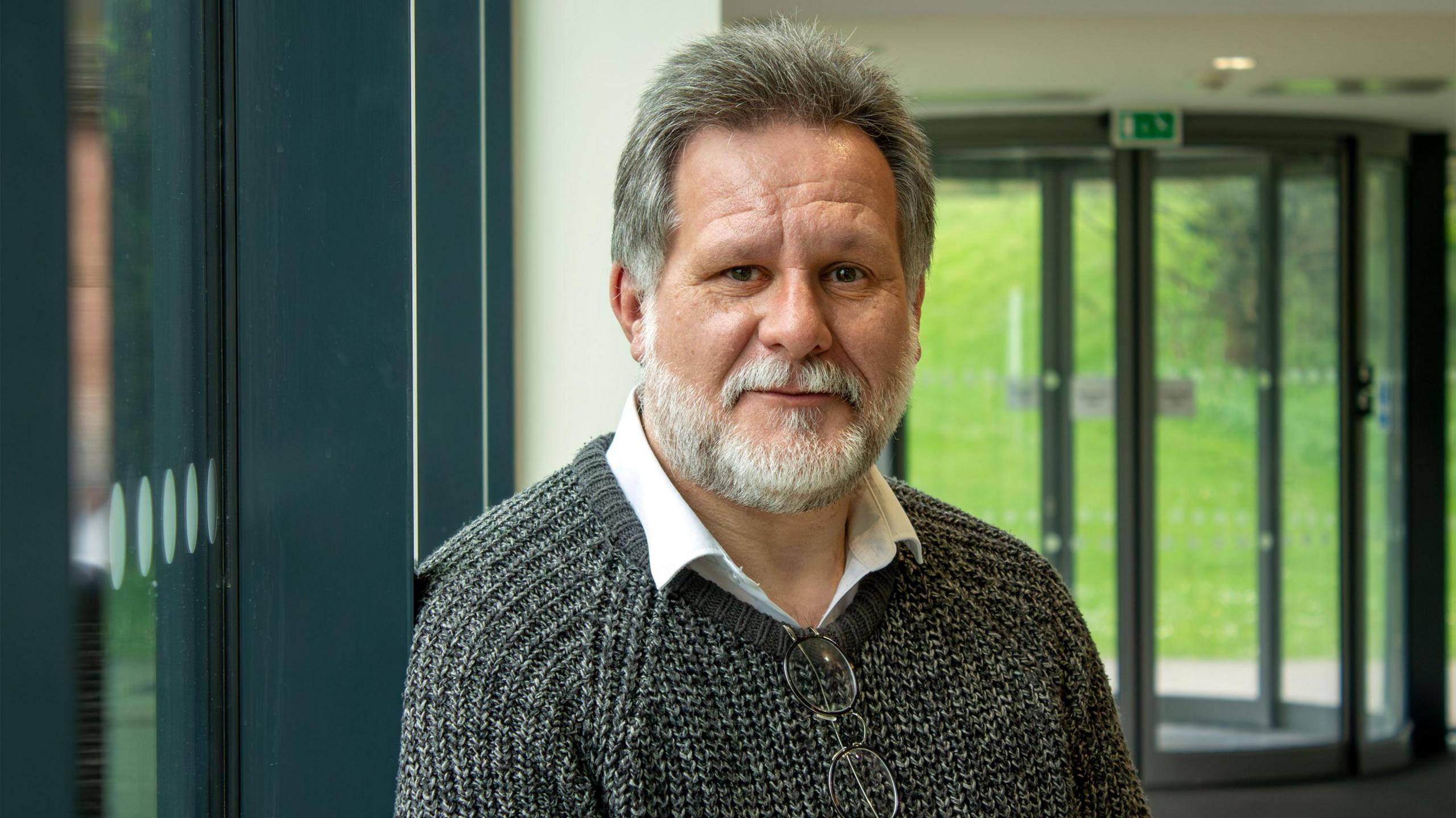

But Professor Matthew Wills, from the University of Bath, believes he might have an explanation to the joke. He said it was rooted in a genuine evolutionary phenomenon called carcinisation - meaning "to become more crab-like".

Over millions of years, nature has reinvented the crab at least five separate times across various lineages of crustaceans in a bid to improve protection and mobility.

These "imposter crabs" have evolved independently through natural selection, as a rounded shell and signature sideways scuttle offer better chances of survival.

Some decapods used to have elongated muscular bodies like a lobster, but they have evolved over time to tuck their tail under as a defence mechanism

Crabs belong to a group of ten-footed crustaceans called decapods.

Some decapods, like lobsters and shrimp, have a thick cylindrical abdomen with a muscular tail for snapping backwards at high speed and burrowing on the seabed.

True crabs, by contrast, live in shallow coastal waters and rocky shores, with a compressed abdomen tucked away under a flattened, rounder shell.

This presents fewer vulnerable areas for predators to grab onto, and enables their legs to move sideways so they can escape quickly and shelter in crevices.

But at least four groups of decapods - including sponge crabs, porcelain crabs, king crabs and the Australian hairy stone crab - are "imposters" that have gradually transformed their shape by tucking their tail underneath.

This means crabs are not a real biological group. They are a collection of decapods that have evolved over millions of years to look the same.

Their compact rounded shell enables crabs to tuck themselves into rock crevices for better protection against predators

Professor Wills, a professor of evolutionary palaeobiology, said imposter crabs sacrifice their muscular abdomen for better armour.

This process of carcinisation is a form of convergent evolution.

"This is where groups that are not closely related come to look, behave, or be in some sense genetically similar, but they don't share a common ancestor that also had that attribute," he said.

"Evolution keeps finding the same answer in different lineages and places."

Professor Wills gave another example of birds and bats, which both developed wings because they face similar environments, despite being different species in "different major branches of the vertebrate tree".

Professor Wills said imposter crabs "sacrifice" their muscular abdomen for better "armour"

"[Crabs] converge because it's an efficient solution to a particular set of physical problems," he explained.

"A compact, broad, armoured body with a tucked abdomen helps with defence, crevice-living, wave-swept hydrodynamics, sideways agility, and broad protection."

Professor Wills said it had been amusing to watch the internet debate unfold, but "the answer is still no", humans will not evolve into crabs.

"The convergent evolution of crabs has happened about five times in history, but it's happened within the group of decapods."

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Somerset

Follow BBC Somerset on Facebook, external and X, external. Send your story ideas to us on email or via WhatsApp on 0800 313 4630.