In her Soviet-era apartment block on the outskirts of eastern Kyiv, Oksana Zinkovska-Boyarska lives with daily power cuts. The lift to her eighth-floor apartment often stops, the lights go out and sometimes the pumps maintaining pressure in the gas central heating fail.

She has a big rechargeable battery pack to keep appliances going, but it costs €2,000 (£1,770) and it only lasts so long. Her husband Ievgen, a lawyer, often has to work by torchlight. Their two-year-old daughter Katia plays by candlelight too.

Amid air raids and cold darkness, Oksana says she and Ievgen worry constantly for Katia. "I can't describe with words the animal fear when you take your child to the shelter during the explosions.

"I have never felt anything like that in my life and I wouldn't want anyone to feel anything like that. The thought that she might be scared because there's no light - this is terrible."

Oksana Zinkovska-Boyarska, pictured with her daughter Katia, says: "I can't describe with words the animal fear when you take your child to the shelter during the explosions"

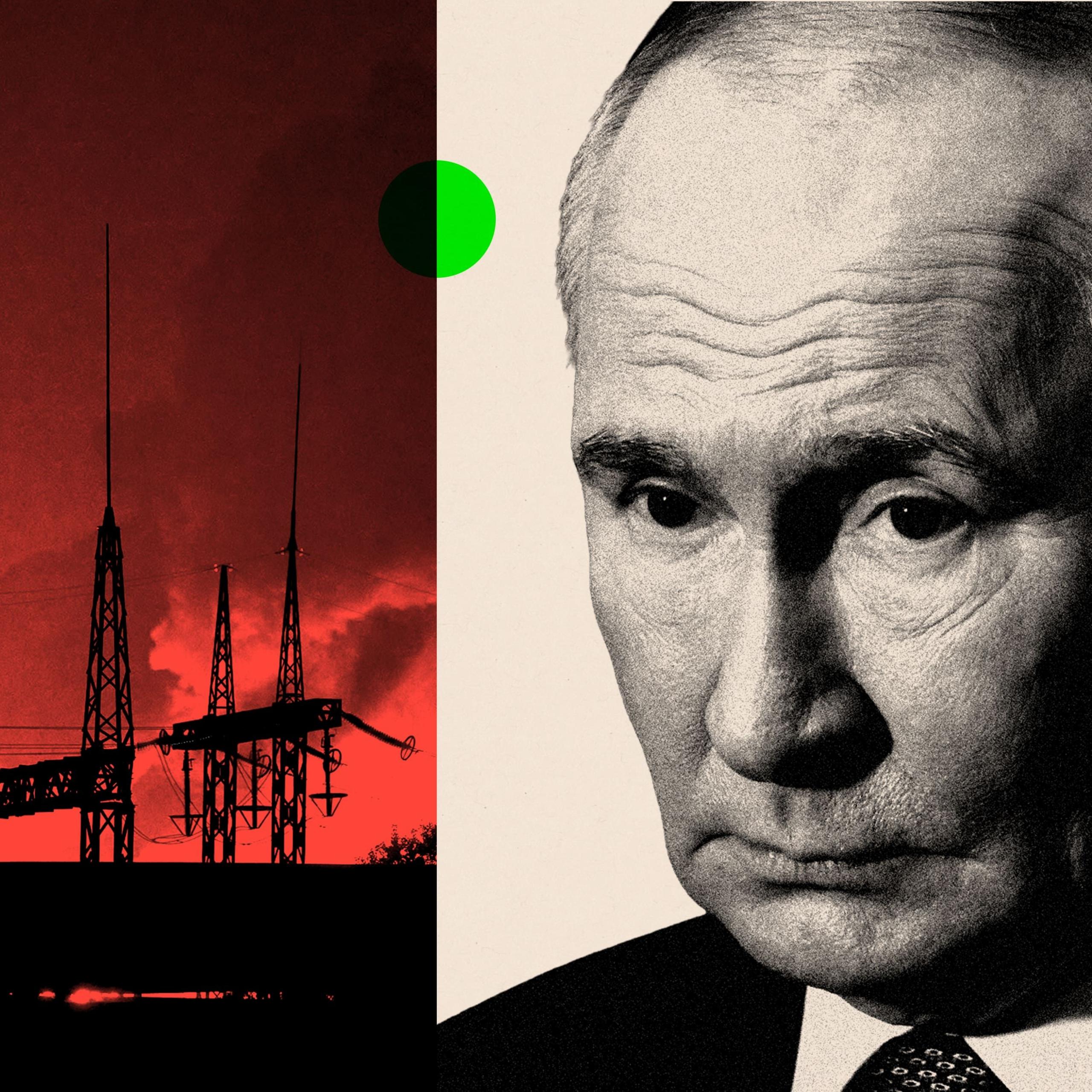

All across Ukraine, families are bracing themselves for even tougher times ahead - a long, cold winter in which Russian President Vladimir Putin attempts to finish off his "special military operation" by striking Ukraine's power supplies.

Just last weekend, a massive drone and missile strike left much of the country for a time without power. Ukrainians are now enduring regular power cuts of up to 16 hours a day.

In winter, temperatures in Ukraine can plummet as low as -20C. One senior government figure told me they expect the next few months to be brutal.

"I think it will be the worst winter of our history," says the official. "Russia will destroy our energy, our infrastructure, our heating. All state institutions should be prepared for the worst scenario."

Maxim Timchenko, the chief executive of DTEK, a large private energy company in Ukraine, says: "Based on the intensity of attacks for the past two months, it is clear Russia is aiming for the complete destruction of Ukraine's energy system."

Ukrainians are now enduring regular power cuts of up to 16 hours a day

But according to one European envoy, it's not just about people being cold at night or without light - there is more to Russia's strategy.

"[This] is also about them not getting any bread from the bakery in the morning and not being able to go to work because there is no power for the factory," says the envoy.

As the official puts it: "The goal of the Russians is to kill our economy."

So how exactly will this warfare tactic play out? And given that almost four years of war have taken their toll, what does the increasing use of this weapon in the war of attrition mean for Ukraine's people - and the endpoint of this long, hard war?

Frozen assets and suspended diplomacy

On the front line, the news is bleak. There are growing signs that the key eastern city of Pokrovsk may fall, giving Russian forces a boost in morale and a fresh platform to seize more of the Donetsk region.

What's more, for now, diplomatic efforts to end the war appear to be on hold.

On the front line, the news is similarly bleak. (Ukrainian servicemen pictured during training in 2024)

Talk of a summit between US President Donald Trump and Russia's Vladimir Putin are on the back burner after Moscow refused to budge from its maximalist war aims and the US imposed sanctions on Russian oil and gas.

"There is currently a pause," a Kremlin spokesman said this week, "the situation is stalled."

All the while, European nations deliberate over what to do with €180bn (£160bn) in frozen Russian assets. They plan to use the cash to raise a so-called "repatriation loan" for Ukraine, repaid only if Russia ever pays reparations after the end of the war.

But a row over how to share the risk has left Kyiv's coffers looking distinctly bare.

Talk of a summit between US President Donald Trump and Russia's Vladimir Putin (pictured together in 2018) are now believed to be on the back burner

Yet it is the energy crisis that is worrying the Ukrainian government most, according to those I spoke to. "People are tired after four years of the war," the official tells me.

"I am afraid they will be demotivated."

Insomnia, missiles and shifting morale

Walk the streets of Kyiv and you'll pass a sea of tired faces - people's eyes are red from a lack of sleep, their rest broken by the air raid sirens.

"I am tired of not sleeping enough," says Yana Kolomiets, 31, a casting director from Odesa. "But... people who fight on the front line are tired [too]."

A recent scientific study suggested that people are three times more likely to suffer from insomnia in Ukraine than in countries at peace.

It tracked the sleep patterns of around 100 Ukrainians over six months, and found the insomnia persisted even on quiet nights. (The research was published by Texty, a data journalism website based in Ukraine.)

There have not been many quiet nights. Russia launched vast numbers of ballistic missiles at Ukraine in October - some 268 in all, the highest monthly total since the full-scale invasion, according to analysis published by the Oboz news site. The same month Russia launched 5,298 Shahed and other bomber drones.

A recent scientific study suggested that people are three times more likely to suffer from insomnia in Ukraine than in countries at peace

Diplomats suggest there is a geographic focus to Russia's tactics, their strikes deliberately targeting gas and electricity transmission networks in eastern Ukraine, rather than power stations in the west of the country.

"They are trying to cut Ukraine in two in terms of energy," one European envoy says. "They want anywhere east of the river Dnipro to be cold this winter."

The aim, one government source told me, is to "instigate an insurrection, so that people go against the government in Kyiv… they are trying to destroy social cohesion."

So concerned is the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs it has already issued a formal warning, saying "the approaching winter poses new risks for Ukrainians... as intensified attacks on energy networks undermine efforts to maintain warmth in homes, schools and health centres".

In October, 56% of 1,008 Ukrainians interviewed by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology felt optimistic about the country's future

Uncertainty over the outcome of the various diplomatic initiatives hasn't helped, either.

And yet opinion polls suggest people in Ukraine may in fact be more hopeful, not less.

Research by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, a pollster, suggested that in October 56% of 1,008 Ukrainians interviewed felt optimistic about the country's future, up from 43% in May.

Sasha, a Kyiv-based financier, explains that Ukrainian morale is volatile, swinging wildly between optimism and pessimism.

"If people talk about an end to the war, they feel hopeful," he says. "But then when the talks fail, they despair."

Oksana, though, is pragmatic: she says that for all the fears for her daughter, they have no choice but to endure it.

"I always think it is much worse at the front line," she adds. "There are boys and girls on the front line who suffer much, much more.

"We can hold on for as long as the front needs it," says Oksana

"I understand my child should not be raised in these conditions, because it is not normal in the civilised world. But we can hold on for as long as the front needs it."

Putin wants a victory he can 'sell'

Earlier this week, thick fog enabled Russian troops to move further into Prokrovsk.

The news out of the city is bleak with daily reports of Russian advances. If it fell, it would be the first major city seized by Russia since Avdiivka in February 2024.

But Russian forces would still only be about 25 miles (40km) from where they began their full scale invasion in 2022, land gained at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky says the Russian high command is throwing so much at Pokrovsk not just because it is tactically significant, but because Putin wants a victory he can "sell" diplomatically to the White House.

The news out of the city of Pokrovsk (pictured in April) is bleak with daily reports of Russian advances

The Russians hope to convince President Trump they are making battlefield gains that will put pressure on Kyiv to sue for peace.

Vadym Prystaiko, Ukraine's former foreign minister and ambassador in London, said Russia wanted to "force this feeling among Europe and westerners – as Russian propagandists have done before – that you can't do anything with Russia, you can't defeat Mother Russia.

"They hope that our partners will force us to lose face and sign the Russian deal, whatever that is."

When I asked President Zelensky if his people could survive the coming winter at a recent press conference, he was clear about the scale of the challenge.

"I don't know what winter will be but we have to prepare in any case," he answered.

"We understand what we have to do, we understand what we need and our partners also know from us what, in the case of difficulties, what volume of electricity we have to import."

Ukraine imports gas from across Europe, including Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia. But it also has massive storage facilities which Russia could target.

Oleksandr Kharchenko, director of the Energy Industry Research Centre, says Ukraine is well placed to protect its energy supply from Russian attacks. "We are better trained, we know how to act, we have no panic," he says.

"We have an understanding of what to do if something is damaged. It will be complicated, it will be a hard winter, there will be a lot of outages but it will be manageable."

War fatigue versus strategic patience

Ukraine's prime minister is confident. Yulia Svyrydenko said Russia's goal was "to plunge Ukraine into darkness. Ours is to preserve the light."

Nonetheless, this may be harder to achieve if Trump focuses on other matters and turns his attention away from Ukraine - likewise if European voters elect governments that are less supportive of Kyiv and cannot wean themselves off Russian energy.

Yulia Svyrydenko said Russia's goal was 'to plunge Ukraine into darkness. Ours is to preserve the light'

The danger is that war fatigue will overcome strategic patience.

But for all the bleak realism of the official government source, even he remains confident. "This winter is the last opportunity for the Russians to defeat us," he said. "And if we make it to 1 April, we will win the war."

I asked one western diplomat why Ukrainians were so unyielding. "They are just bloody-minded," the envoy said, and pointed to Ukraine's long history of withstanding hardship.

"They say they have survived the Germans, the Poles, the Turks, the Lithuanians and now they can survive the Russians."

And yet for many in Ukraine, life is going on as usual - or as usual as it can.

For many in Ukraine, life is going on as usual - or as usual as it can

At the Dynamo Stadium in Kyiv, floodlights are on full beam and a game of football is being played - Dynamo Kyiv versus Shakhtar Donetsk, a rough, partisan game, the hardcore fans, known as ultras, wear masks and chant at their opponents.

One of the few signs that this is taking place in a city at war is the number of people there: the stadium can seat more than 16,000 people but only 4,300 fans are allowed in, owing to the capacity of the stadium's bomb shelters.

The fans have come from all parts of society – young and old, families and friends. Servicemen and women are there too, earning applause from the crowds, who part to let them pass through.

'This is just representative of who Ukrainians are,' says Rodion, a 17-year-schoolboy. 'Even though we get bombed every day, even though a drone can hit the stadium anytime, we are still going'

"It's really important to continue to live," says Anatoliy Anatolich, the match announcer, a TV and social media host.

In his view, coming to the football in itself is an act of defiance.

"[It shows] everyone that we are not going to leave our country in this hard period… We've got to be here when we win."

Five minutes before the end of the match, the chanting suddenly stops. The fans put their hands on their hearts and sing the national anthem.

Soon the whole stadium was singing as one; a crowd divided by teams, but united by country.

Top image credit: AFP/Getty Images

More from InDepth

How Russia is quietly trying to win over the world beyond the West

- Published25 August

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.