Woman installed first north Wales phone 'to listen to opera'

- Published

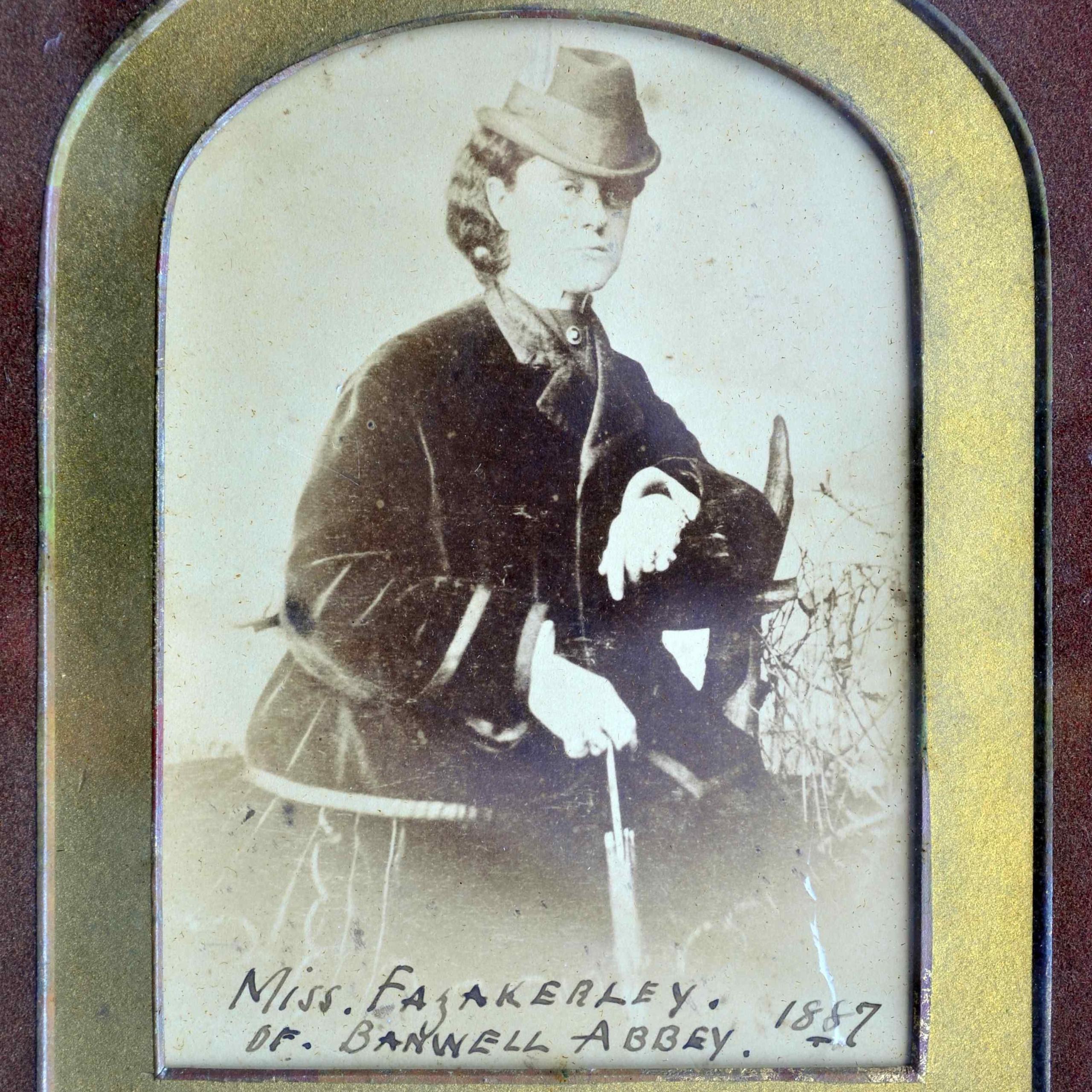

Emily Fazakerley may be a million miles removed from Bob Hoskins or Maureen Lipman, but even she knew it was good to talk.

Because in 1881, philanthropist Emily had the first private telephone installed in north Wales.

The reason? So she could listen to an operatic performance at the Denbigh Assembly Rooms, about half a mile from her Plas Castell mansion, in the shadow of the market town's castle.

Provided by the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephone Company – a subsidiary of the Bell Telephone Company - it came just five years after Alexander Graham Bell had patented the device.

Emily Fazakerley was renowned for her flamboyancy and work in the community

Emily Augusta Gillibrand Fazakerley was born on Anglesey in 1840, daughter to Lancastrian-landed aristocrat Henry Hawarden Fazakerley, who owned vast swathes of north Wales and North-West England.

Growing up in Chorley, she moved back to Wales in the 1850s, following the deaths of her sister, brother and father in quick succession.

Living at Plas Castell with her mother and remaining sister, Emily developed a strong but somewhat whimsical personality, which saw her foster her two loves: modern innovations, and helping her community.

An 1878 example of the sort of telephone which Emily would have had installed in her house in 1881

Clwyd Wynne, chair of Denbigh Museum, said: "[Emily] loved to be talked about, but for the right reasons. Her telephone was clearly a massive act of showing off, but even that was done to please six of her friends, who were able to listen to the opera concert with Emily, through rubber ear trumpet extensions.

"I think there were telephones in south Wales before that, probably to do with the mines, but hers was the first up here, certainly the first privately-owned one."

He added how Emily would buy up a travelling tinker's entire stock, then call an impromptu tea party for every woman in the town, "high and low", in order to gift the pots, pans, brushes and utensils.

Calls for 'iconic' phone box to return

- Published9 July

Abandoned phone box to become community museum

- Published28 December 2024

50 years since the first mobile phone call!

- Published3 April 2023

"In 1885 she revisited Denbigh in a coach and four horses, which the local newspaper reported was more usual of royalty, certainly never seen outside of London.

"Nevertheless the people loved her – turning out in their hundreds to greet her – and she appears to have loved them back, gifting to the crowds upwards of £50 in one afternoon, an enormous sum for those days."

Emily sought to use her money and immagination in order to make ordinary people's lives better

At the time she had her telephone installed, the Post Office and the Bell Telephone Company were locked in a bitter legal dispute as to whether a phone was a separate device to a telegraph, over which the Post Office held a government-granted monopoly.

"Telephones weren't telephones as we know them today," said Clwyd.

"They needed to be plugged into the existing telegraph network in order to be connected.

"By commissioning her own entirely private line she must have circumvented the raging battles going through the courts at the time."

Emily donated the land on which Banwell's first fire station was housed

As ill-health began to overtake her in the 1880s, Emily moved to another of her family's seats, Banwell Abbey in Somerset.

Historian Harry Mottram wrote of how she was equally as admired in the West Country as she had been in Wales.

"Emily was to leave a lasting impression when she arrived by train on the Strawberry Line at Banwell and Sandford Station," he said.

"Looking slightly severe in her funereal black gown the Welsh aristocrat cut an exotic image of a cross between Mary Poppins and Queen Victoria."

He describes how she immediately set about establishing one of the first professional fire brigades outside of London.

"Depicted as a "wealthy, eccentric, lady bountiful" on Barry Mather's website about the history of Banwell: "The wealthy spinster of the parish was noted for her acts of generosity to the community.

"These included donating land and a cottage to set up a fire station in 1887, and buying a horse drawn fire engine and uniforms for the new fire brigade.

"Like many rural villages, Banwell was almost entirely thatched, and fuelled by open fires, making it highly prone to blazes, so she provided the very latest in fire-fighting equipment to improve their lives."

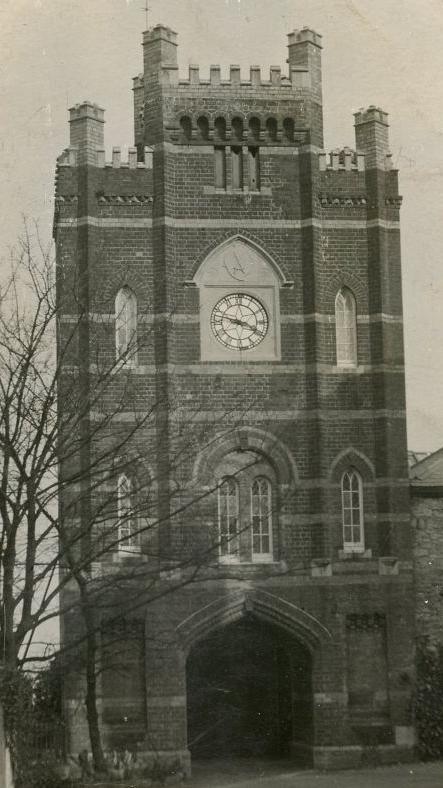

In 1884 Emily had the clock from this tower moved from Plas Castell, Denbigh to replace the broken example in Banwell

But in 1884 Emily fell foul of local opinion, when – in another attempt at local improvement – she replaced the broken clock at Banwell's St Andrew's Church, with a 24-hour gas-lit timepiece she'd moved at great expense from her own home in Denbigh.

"Believing she was helping, Miss Fazakerley had one brought from her family home in Denbigh and paid for the workmen to have it installed on the church tower," wrote Harry.

"Lit by gas which automatically switched on at night it appeared to be the perfect timepiece. However this was the 19th Century and folks weren't so keen on all modernisations.

"It would be the equivalent of a vast digital clock being put there today along with neon lighting. It would do the job but somehow not in the right way.

"The villagers took against the new clock and made their feelings felt. It must have been a painful moment in the relationship between the parishioners and Emily – but she got the message and had the clock removed."

Emily was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London, which is also the resting place of William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Babbage and Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Emily died tragically young, at just 48, on 17 June 1888, and was buried in her family's plot in London.

Her north Wales family home at Plas Castell lived on after her, as the residence of Thomas Gee, an influential Welsh Nationalist; which would be visited by prominent Welsh MP Thomas Ellis and future Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Plas Castell, Denbighshire, lived on after Emily's death

Today it is a boutique hotel, and if you have a bit of spare change in your pocket, it's currently up for sale for £1.1m.

"As we've tried to put together Denbigh's story for the launch of the museum's new premises, we've learnt that the town's collective history is made up of all these magnificent individual stories like Emily's," said Clwyd.

"Once great in the 19th Century, but falling on harder times in more recent years, Denbigh can take inspiration to rise again into somewhere where people are proud to come from."