Violence, overcrowding, self-harm: BBC goes inside one of Britain’s most dangerous prisons

- Published

There’s chaos in HMP Pentonville.

A piercing alarm alerts us to what prison officers describe as an “incident”. There’s a cacophony of slamming metal doors, keys jangling, and shouts and screams from inmates as officers race to see what’s happened. We run behind as they head to where the trouble is.

Cell doors and chipped painted white bars are just about the only scenery as we move through this chaotic and nerve-jangling environment.

A muffled walkie-talkie tells us it’s a case of self-harm. An inmate who’s been locked up for most of the day has carved “mum and dad” into his arm with a sharp object. A quick glance into the cell and the sight of blood. A prison officer crouches down, stemming the flow.

Prison gangs: ‘I've chopped people, attacked staff, hidden drugs’

- Published15 October 2024

Prison officers deal drugs and ask inmates for sex, BBC told

- Published14 November 2024

The BBC has been given rare access to HMP Pentonville men's prison in north London at a time of major crisis for jails in England and Wales.

Next week, with prisons across the country running out of cells for new inmates, the government will release some offenders early in a controversial scheme aimed at easing the overwhelming pressure on a system on the brink of collapse.

Over the course of two days inside Pentonville this week, we were confronted with the stark reality of this crisis.

‘Fights, killings…all sorts could happen’ - Inside one of the UK's most dangerous prisons

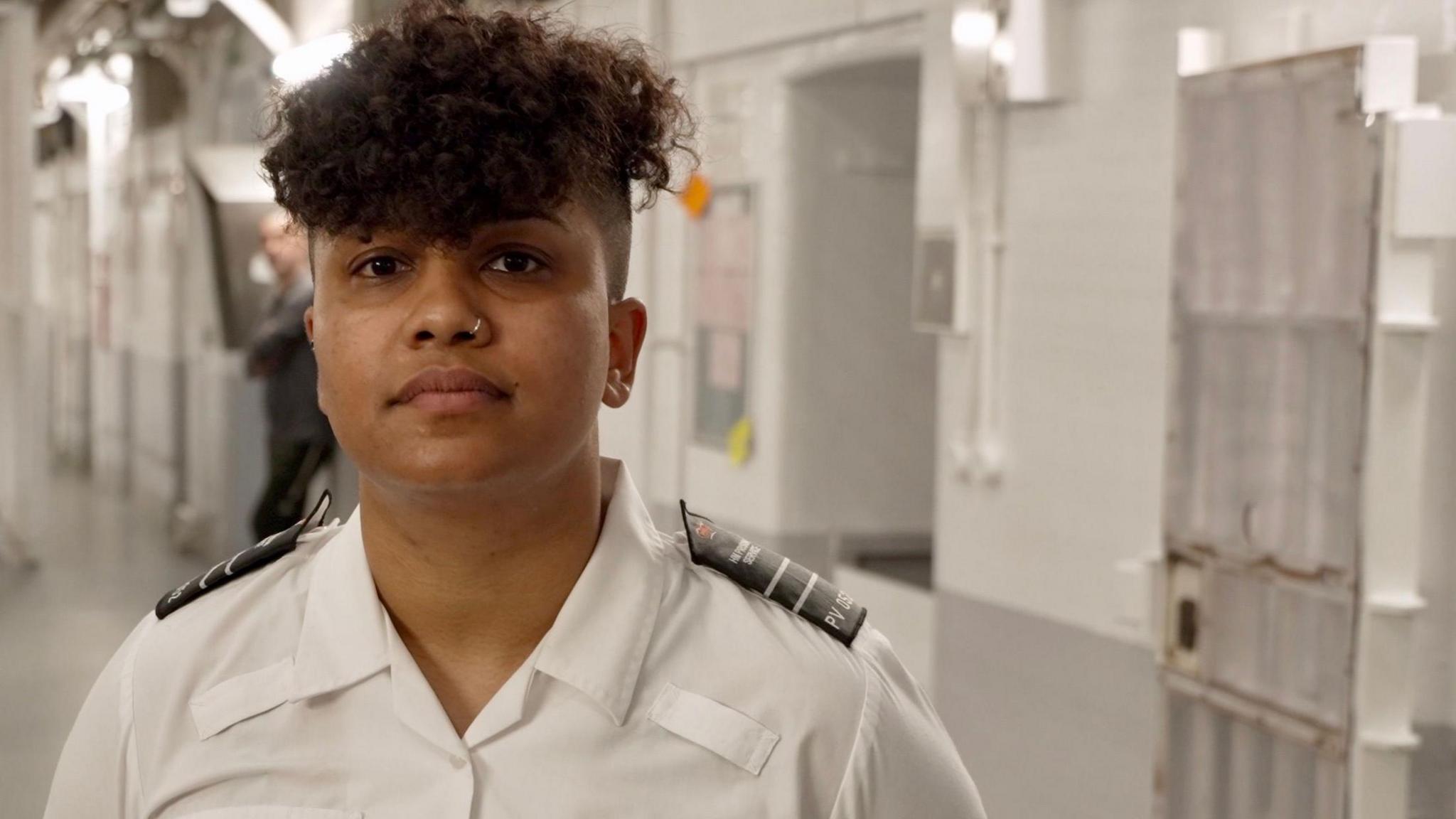

Shay Dhury has been a prison guard at HMP Pentonville for nearly five years

The pressure on staff is immense. In just half a day, we hear six alarms. The day before there were more than 30. Prison officers don’t know what they’re running towards behind those locked and bolted doors. Blood, violence or even death are all possibilities.

Shay Dhury has been a prison officer here for almost five years and says she’s never seen it this bad. Recently, both her wrists were broken as she tried to separate two gang members during a fight. She believes gang-related crime is one of the main reasons there are so many people in prisons, especially Pentonville.

“They go for each other - and when two people go, other people go,” she says. “It ends up us just trying to stop the fight. It gets really messy sometimes - stressful, yeah.”

HMP Pentonville was built in 1842 and is largely unchanged structurally in 180 years. Originally designed to hold 520 people in single cells, it now has an operational capacity of 1,205, with two prisoners packed into each cell.

The jail is dangerously close to capacity - with just nine beds remaining when we are there. And humans are not the only inmates here: mice and cockroaches are rife.

The government says Pentonville epitomises the challenges facing ageing, inner-city prisons with transient populations who have varied and complex needs.

More than 80% of Pentonville inmates are on remand, which means they are awaiting trial. The rest have been convicted of serious crimes including murder, rape, and drug offences.

Remand is at a 50-year high across England and Wales - and that’s partly down to a backlog in the criminal courts. Ministry of Justice (MoJ) figures show the Crown Court system has a backlog of more than 60,000 cases. The Magistrates Court has a backlog of more than 300,000 cases.

HMP Pentonville

It costs £48,949 to keep a prisoner in Pentonville for a year, £52.4m for the whole population

57% of inmates live in crowded accommodation

Those not in training or education spend just one hour a day out of their cell

104 incidents of self harm were recorded in March 2024 - the most in a single month since records began

There were seven suicides in the prison between 2019 and 2023

One prisoner has been trying to get his leaking toilet fixed for three weeks

Tom - not his real name - is on remand. His cell is tiny. It’s around seven feet by six feet (2m x 1.8m) and has a pungent smell of urine, faeces, and rotten food. A bunk bed takes up most of the space. The toilet, in the corner beside the sink, is leaking and there are wet splashes on the floor.

“I've been telling them about that for three weeks,” Tom says. “I could fix it - I'm actually a plumber - but it had no washers in there.”

Overcrowding impacts all areas of life inside. With fewer officers to inmates, prisoners’ needs can’t always be met, which means some, like Tom, are living in cells that aren’t properly operational for several weeks when repairs are needed.

Michael Lewis says his former cell mate tried to take his own life

Michael Lewis is inside for drug offences. He’s 38 and has been in and out of jail for several years, but hopes this will be his last stint.

“It’s hard to rehabilitate yourself in a place where you've got gang violence, postcode wars, drug violence, money wars,” he says, highlighting how overstretched staff are.

“They're trying to do this, this, this and this - but now you want help as well? So it's hard.”

He tells me about the night he woke to find his former cellmate trying to hang himself.

“I could tell he wasn't dead because he was still breathing, he’s still warm,” Lewis says, describing the wait for a prison officer to come to help.

“He can't open the door on his own at night - keys and everything, security risk,” Lewis explains. “Waited for another staff member - and as soon as he came in he saw to him.

“He survived.”

'I would rather die'

I’ve been to several prisons and the situation at Pentonville is the worst I have seen.

The staff seem to be doing what they can in very difficult circumstances, fighting problems, crises, and violence - but they are often struggling to cope.

Sixteen people will be released from here next week when the government releases thousands of offenders early. The prison’s governor, Simon Drysdale, says that will alleviate some of the pressure and mean more people who’ve been sent to Pentonville - a reception prison serving all London courts - can be transferred on to other jails because they too will have more available cells.

“Our total focus is on making sure that we've got space and capacity,” Mr Drysdale says. “That takes up a large proportion of our thinking space and a lot of the staff's time, and because of that we don't get as much time as we would like to think about things like getting men into more meaningful work.”

But some Pentonville inmates are doubtful that 16 inmates being released from here will make a difference. One, who didn’t want to be filmed, speaks to us while crouched on the floor with his back against the wall.

“Nothing will ever change,” he says, sobbing.

“They don’t care about us. I would rather die.”

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this story, support and advice is available via the BBC Action Line.

Sign up for our morning newsletter and get BBC News in your inbox.