'It's scary to think I could have died' - the Americans coming back from fentanyl addiction

Kayla says she became "instantly addicted" to fentanyl as a teenager

- Published

Kayla first tried fentanyl as a troubled 18-year-old, growing up in the US state of North Carolina.

"I felt like literally amazing. The voices in my head just completely went silent. I got instantly addicted," she remembers.

The little blue pills Kayla became hooked on were probably made in Mexico, and then smuggled across the border to the US - a deadly trade President Donald Trump is trying to crack down on.

But drug cartels aren't pharmacists. So, Kayla never knew how much fentanyl was in the pill she was taking. Would there be enough of the synthetic opioid to kill her?

"It's scary to think about that," Kayla says, reflecting on how she could have overdosed and died at any moment.

In 2023, there were over 110,000 drug-related deaths in the US. The march of fentanyl, which is 50 times more potent than heroin, seemed unstoppable.

But then came a staggering turnaround.

In 2024, the number of fatal overdoses across the US fell by around 25%. That's nearly 30,000 fewer deaths – dozens of lives saved every day. Kayla's state, North Carolina, is at the forefront of that trend.

Why fatal overdoses have fallen so sharply

One of the explanations is a commitment to harm reduction. This means promoting policies that prioritise drug users' health and wellbeing rather than criminalising people - a recognition that in an era of fentanyl, drug-taking too often ends with death by overdose.

In North Carolina, where Kayla still lives, and where overdose fatalities are currently down by an impressive 35%, harm reduction strategies are well-developed.

Kayla no longer takes street drugs. And she's a client of an innovative law enforcement assisted diversion (LEAD) programme in Fayetteville. It's a partnership between the town's police and the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. Together, they work to divert substance users away from crime, and get them on the road to recovery.

Lt Jamaal Littlejohn watched his own sister deal with substance use disorder

"If someone's stealing from a grocery store, we run their criminal history. And often we see that the crimes they're committing appear to fund the addiction they have," says Lt Jamaal Littlejohn.

This might make them a candidate for the LEAD programme, meaning they can get support to tackle their addiction, and can start thinking about secure housing and employment.

The proponents of LEAD say it isn't about being soft on crime. Drug dealers still go to prison in Fayetteville. "But if we can get people the services they need, it gives law enforcement more time to deal with bigger crimes," argues Lt Littlejohn, who watched his own sister struggle with a substance use disorder.

Listen to Assignment: Drugs, Overdose, Hope on The Documentary Podcast on the BBC World Service

Kayla has blossomed. She's such a long way now from the days when she used prostitution to fund her fentanyl habit. As part of the LEAD process, her criminal record has been wiped. She recently graduated as a certified nurse assistant, and is now working in a residential home.

"It's like the best thing ever. This is the longest time I've been clean," she says.

Critical to Kayla's recovery has been treatment. She's been taking methadone for nearly a year when she tells her story to the BBC. "It's keeping me from going back," she believes.

Methadone and buprenorphine are medications used to treat opioid use disorder. They stem cravings and stop painful withdrawal. Nationwide, treatment has played a role in puncturing the overdose fatality statistics.

In North Carolina, it's been a game-changer: more than 30,000 people were enrolled in a programme in 2024, with numbers climbing in 2025.

'You're still playing Russian roulette, but your odds improve'

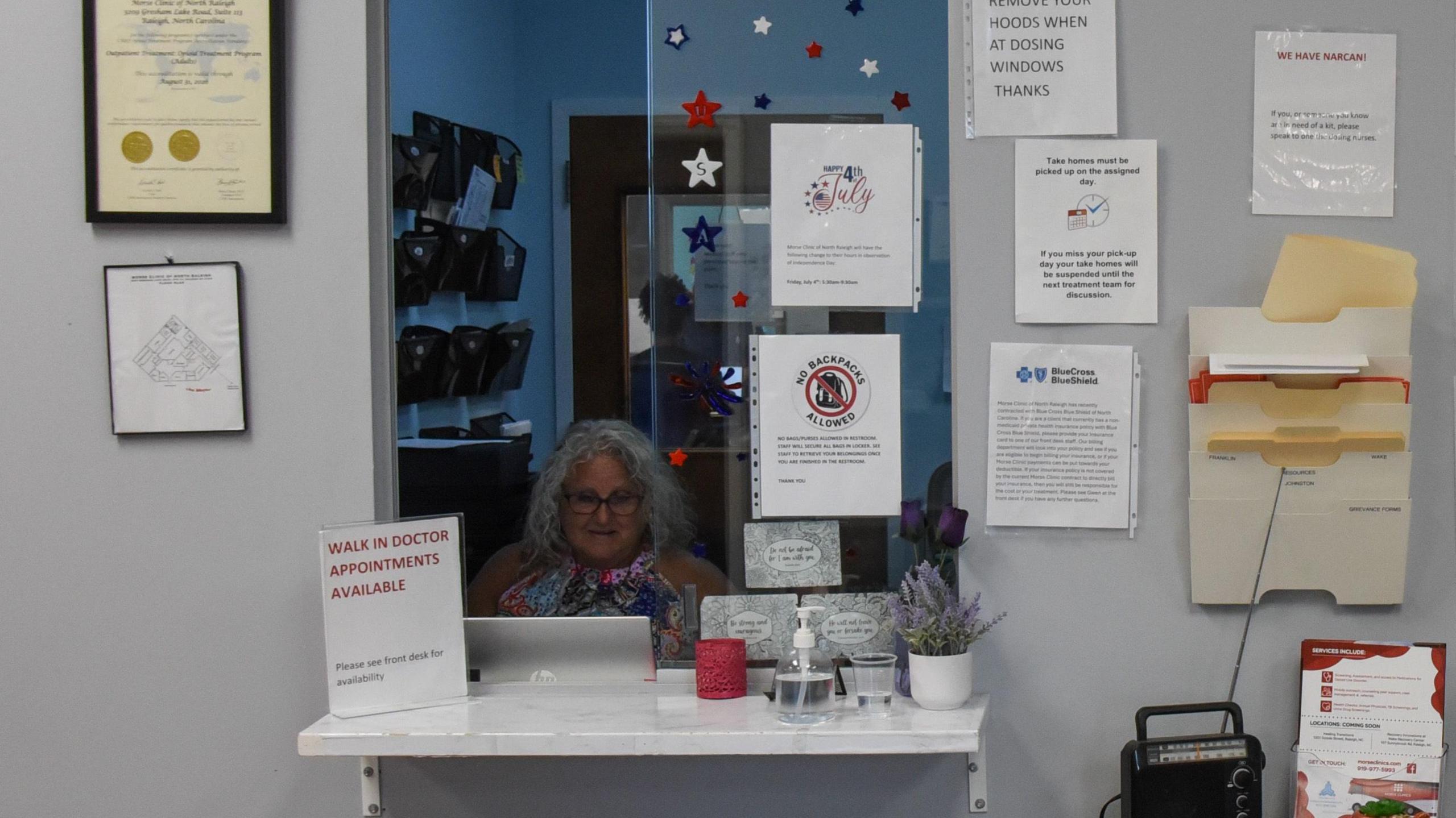

This Morse Clinic experiences its busiest time soon after 05:30

At 09:00 at one of the Morse Clinics in the state capital of Raleigh, two or three people wait their turn in reception.

"The busiest time is 5.30am to 7am, so before work," says Dr Eric Morse, an addiction psychiatrist running nine clinics offering medication assisted treatment (MAT) in North Carolina. "Most of our folks are working - once they're sober, they show up to work on time every day."

The clinic runs a finely-tuned operation. After patients check in, they're called to a dosing window to receive their prescription. They're in and out in minutes.

They'll randomly be drug tested for illicit narcotics. Dr Morse says around half his patients are still testing positive for opioids bought on the street, but he doesn't see this as failure.

"Maybe you're using once a week and you're used to using three times a day… You're still playing Russian roulette with fentanyl but you've taken a whole bunch of bullets out of the chamber, so your survival rate goes up significantly," says Dr Morse.

This is harm reduction. So rather than be expelled from the treatment programme, patients who get a positive drug test are given extra support and counselling. Dr Morse says 80-90% will eventually stop using street drugs altogether. And in time, many will taper off their medication too.

The abstinence debate

Not everyone thinks this is the right approach.

Mark Pless is a Republican who sits in North Carolina's state House of Representatives, and used to be a full-time paramedic. He points out that illegal drug-taking starts with a choice.

And he doesn't believe in harm reduction. In particular he's against treating opioid use disorder with medications like methadone or buprenorphine.

"You're replacing an addictive product with another addictive product," he says. "If you have to take it in order to stay clean, it's still addictive. We've got to figure out how to get people to where they can do better – we can't leave them on drugs forever."

He favours abstinence treatment programmes, when drug users go "cold turkey".

But there's pushback from health professionals in North Carolina.

"I believe there are multiple paths to recovery," says Dr Morse. "I'm not pooh-poohing abstinence-based treatment - except when you look at the medical evidence."

Dr Morse references a Yale University study from 2023, external analysing the risk of death for opioid users in a treatment programme compared to people not in treatment. The study suggested that someone in abstinence treatment was as likely - or more more likely - to have a fatal overdose as a person who wasn't in treatment and was continuing to use street opioids like fentanyl.

Treatment aside, another drug is helping.

Naloxone is widely available, and used as a nasal spray it reverses the effect of an opioid overdose, helping someone breathe again. In North Carolina in 2024, it was administered more than 16,000 times. That's potentially 16,000 lives saved – and these are only the overdose reversals that have been reported.

"This is as close to a miracle drug as we can ever imagine," says Dr Nabarun Dasgupta, a scientist specialising in street drugs at the University of North Carolina.

Dr Nabarun Dasgupta hails the benefits of naloxone

Many users of narcotics like cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin want to know that what they're taking won't kill them. Some people use test-strips to check for fentanyl, because they know it's been implicated in so many fatal overdoses.

But the strips don't identify all potentially harmful substances. Dr Dasgupta runs a national drugs-testing laboratory. Users send him a tiny bit of their drug supply via local non-profit organisations.

"We've analysed close to 14,000 samples from 43 states over the last three years," he says.

A generational shift

Testing drugs for potentially dangerous additives is an additional weapon in the harm reduction armoury. Dr Dasgupta believes another reason for decreasing overdose fatalities in the US is that young people are avoiding opioids like fentanyl.

"We see a demographic shift. Generation Z are dying of overdose much less frequently than their parents or their grandparents' generations were at the same age," he says.

Dr Dasgupta isn't entirely surprised 20-somethings are steering clear of opioids. A shocking four out of 10 American adults know someone whose life has been ended by an overdose.

It was this epidemic of death, set in train in the 1990s by prescription opioids, that motivated North Carolina's former attorney general - now the state governor - to move against powerful corporations benefitting from so many Americans' dark spiral down into addiction.

Josh Stein picked up the phone to his counterparts in other states, and took a leading role in co-ordinating legal action against opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers.

North Carolina Governor Josh Stein took a leading role in co-ordinating legal action against opioid manufacturers

"There was a Republican attorney general in Tennessee, I'm Democrat in North Carolina… But we're all caring about our people and we're all willing to fight for them," Stein reflects.

The upshot, after years of intense negotiations, was an Opioid Settlement totalling some $60bn (£45bn). This is money that huge companies have agreed to pay to US states, to be used for the "abatement of the opioid epidemic". North Carolina's share is around $1.5bn.

"It has to be spent in four ways – drug prevention, treatment, recovery, or harm reduction. I think it's transformative," says Governor Stein.

Meanwhile, funding from the national government is uncertain. The cuts to Medicaid included in President Trump's One Big, Beautiful Bill Act could have a tremendous impact on this area.

In the Morse Clinics in Raleigh, 70% of patients depend on Medicaid. If they lose health insurance, will they end treatment and become more vulnerable to death by overdose? Although North Carolina's drug fatality statistics look optimistic, thousands of people are still dying - and the state's black, indigenous and non-white populations haven't experienced the same rates of decrease.

And there remain other states that have witnessed a stubbornly slower rate of decrease in lethal overdoses - including Nevada and Arizona.

Kayla credits Charlton Roberson, her mentor at North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition, with being instrumental in her recovery

No one is complacent. Least of all Kayla.

In the grip of fentanyl for three long years, she never overdosed herself, but she did have to save her friends. Kayla's parents didn't know what to do with her.

"They kind of gave up on me - they thought I was gonna be dead," she remembers.

Kayla credits Charlton Roberson, her harm reduction mentor, as being instrumental in her recovery. Her aim now is to taper off methadone and become medication- and drug-free. She also wants to find a job in a hospital.

"I feel more alive than I ever did when I was using fentanyl," she says.

If you've been affected by the issues in this story, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

Related topics

More weekend picks

- Published27 October 2024