Is Labour's 2030 green energy goal realistic and how would it affect bills?

Labour plans to invest in wind and solar power to end the use of fossil fuels for electricity by 2030

- Published

Keir Starmer's proposals for a publicly-owned company called Great British Energy to invest in clean and renewable energy are a central plank of Labour’s plans to almost entirely remove fossil fuels from UK electricity production by 2030, five years earlier than current government plans.

But there are two criticisms of this goal.

The first comes from the Conservatives, who argue that this rapid decarbonisation timetable will push up households’ energy bills, external.

The second comes from some energy analysts who simply don’t think electricity decarbonisation as soon as 2030 is practically achievable.

So are these criticisms fair?

There’s no question that the Labour target is highly ambitious.

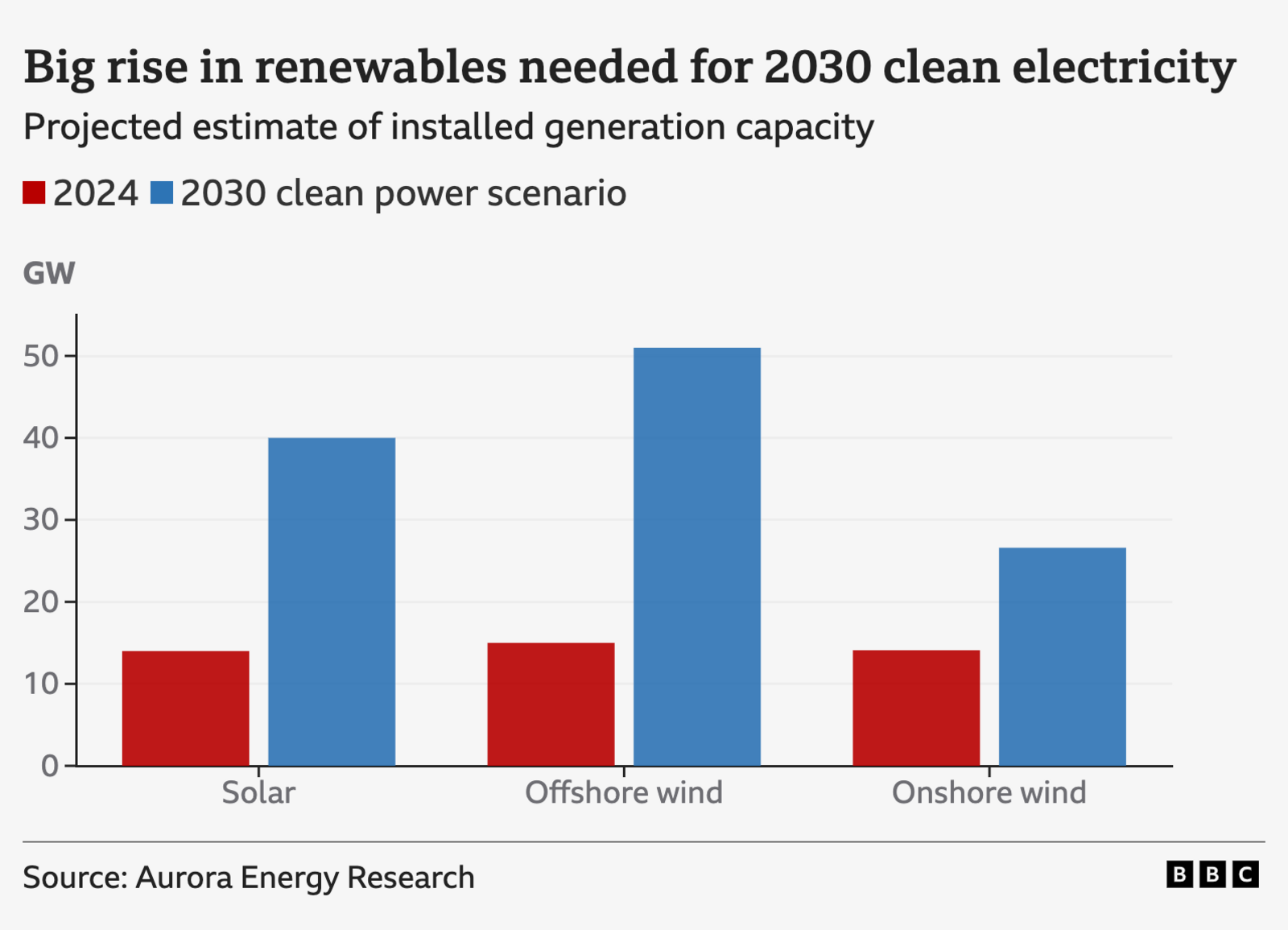

According to estimates from Aurora Energy, external (who were commissioned by the right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange to carry out the research), it would require the total installed UK offshore wind generating capacity to more than triple over the next six years.

Solar electricity generation and onshore wind generating capacity would need to roughly double.

This would be to replace the electricity currently provided by gas-fired power stations.

Would it push up bills?

Most energy experts agree decarbonisation will, in the longer term, be good for household energy bills, external because the UK would be less reliant on imported and internationally traded natural gas and oil for generating power - fossil fuels whose prices can be extremely volatile.

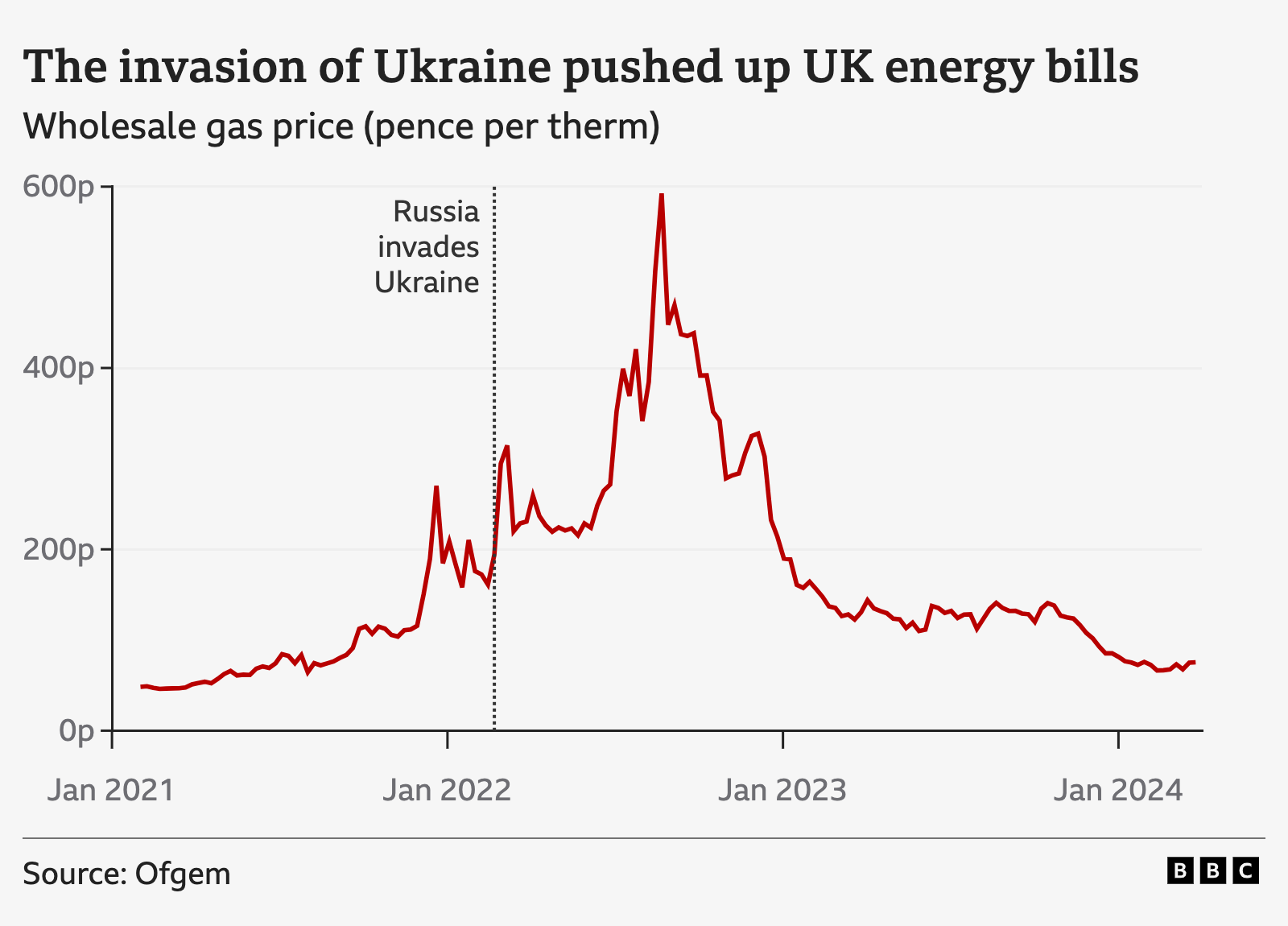

The massive spike in UK households’ bills in recent years has mainly reflected the surge in European wholesale gas prices that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the choking off of gas supplies to the entire continent.

However, the up-front investment in new solar panels and wind turbines required for the UK to decarbonise, in the short and medium term, will come at a cost - and that could well be reflected in households’ bills.

This is a cost that would materialise under the Conservatives’ policy of decarbonising electricity generation by 2035 too, of course.

But all else being equal, a faster decarbonisation effort would mean those costs being passed on faster.

Yet all else might not be equal.

If there were to be another 2022-style global fossil-fuel price shock at some point over the next decade it might be the case that UK households will prove better off financially by moving to renewable energy more quickly.

So in terms of how much a faster electricity decarbonisation might cost - or save - households it’s not very credible to put a cash figure on it. Labour is claiming their plan would save households £300 by 2030.

But the reality is that it would heavily depend on what happens to fossil fuel prices over the coming years.

Is it achievable?

On the second criticism, that electricity decarbonisation can’t be done by 2030, the reality is that experts are divided.

Some, such as Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at the University of Oxford, who was commissioned to produce a cost of energy review for the UK government in 2017, insist Labour’s target is “unachievable”.

But Chris Stark, the former chief executive of the government’s Independent Climate Change Committee, says that while it would take a “Herculean effort” it could, just about, be done.

One of the biggest (and underappreciated) obstacles in terms of hitting the 2030 target is not the cost of installing new solar panels and wind turbines, but the practical difficulty - due to planning regulations and local opposition - of upgrading the UK’s electricity grid network.

The grid is made up of the pylons and cables and substations needed to transmit electricity around the UK from the power stations and wind and solar farms where it is generated to the households and businesses who use it.

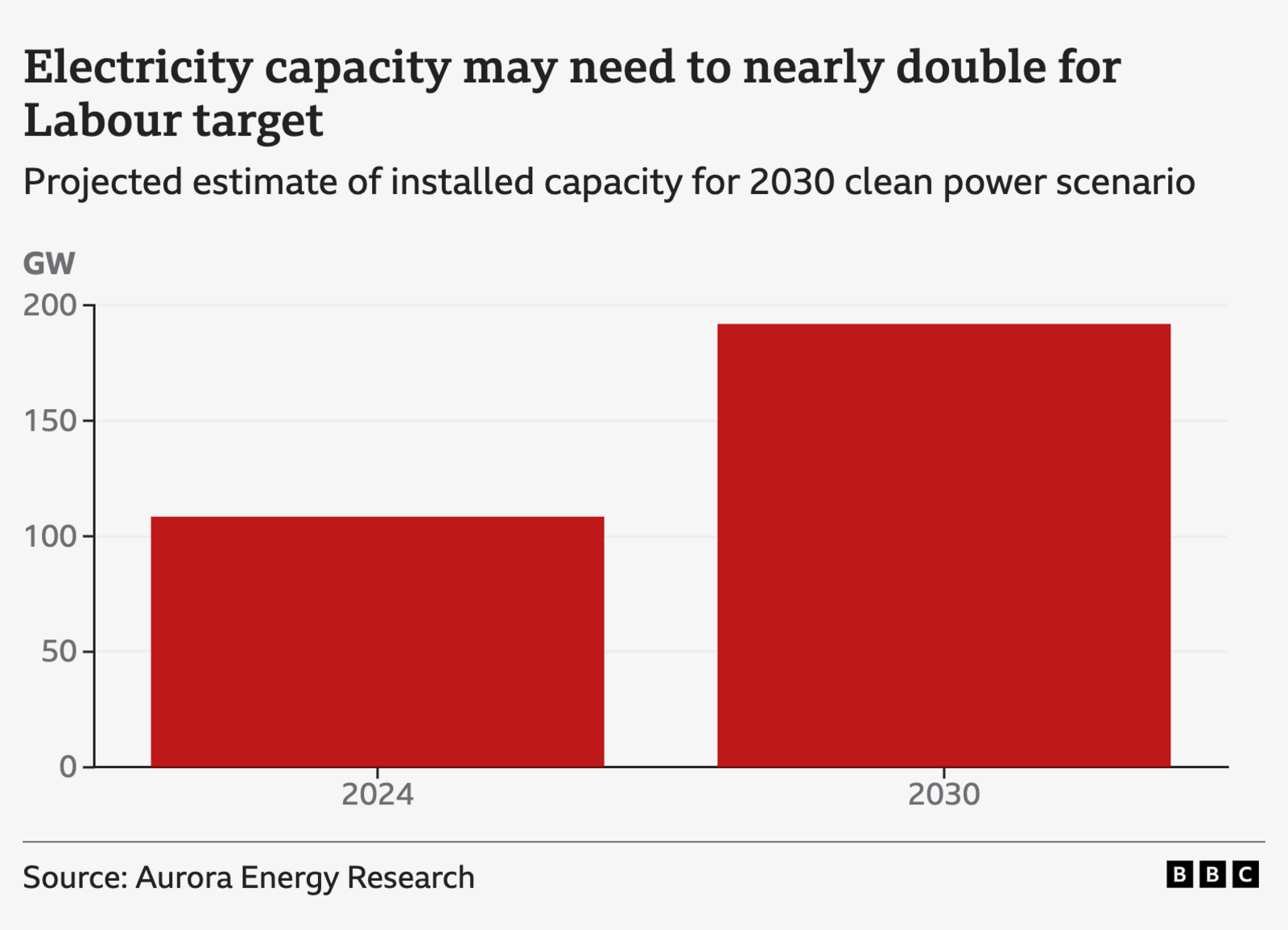

Under Labour’s plans it’s estimated that total UK electricity capacity would need to almost double by 2030.

This additional capacity would be required to provide electricity, among other things, for new electric heat pumps to warm peoples’ homes (replacing gas-fired boilers) and also the electric cars (replacing petrol and diesel vehicles) that people are expected to be driving in the coming years.

Meeting that surge in demand for electricity will require a vast grid infrastructure construction effort.

As the head of the International Energy Agency, Fatih Birol, put it, external last year: “We must invest in grids today or face gridlock tomorrow.”

BBC Verify brings together journalists and experts from across BBC News. We fact-check, verify video, counter disinformation and explain complex stories in the pursuit of truth. BBC Verify journalists have a range of forensic investigative skills and use open source material to inform our storytelling.

We are putting transparency at the heart of what we do, to show you how we know what we know and why you can trust it. If there is a story you'd like BBC Verify to look at, please get in touch below.