The struggle for justice in one English town

- Published

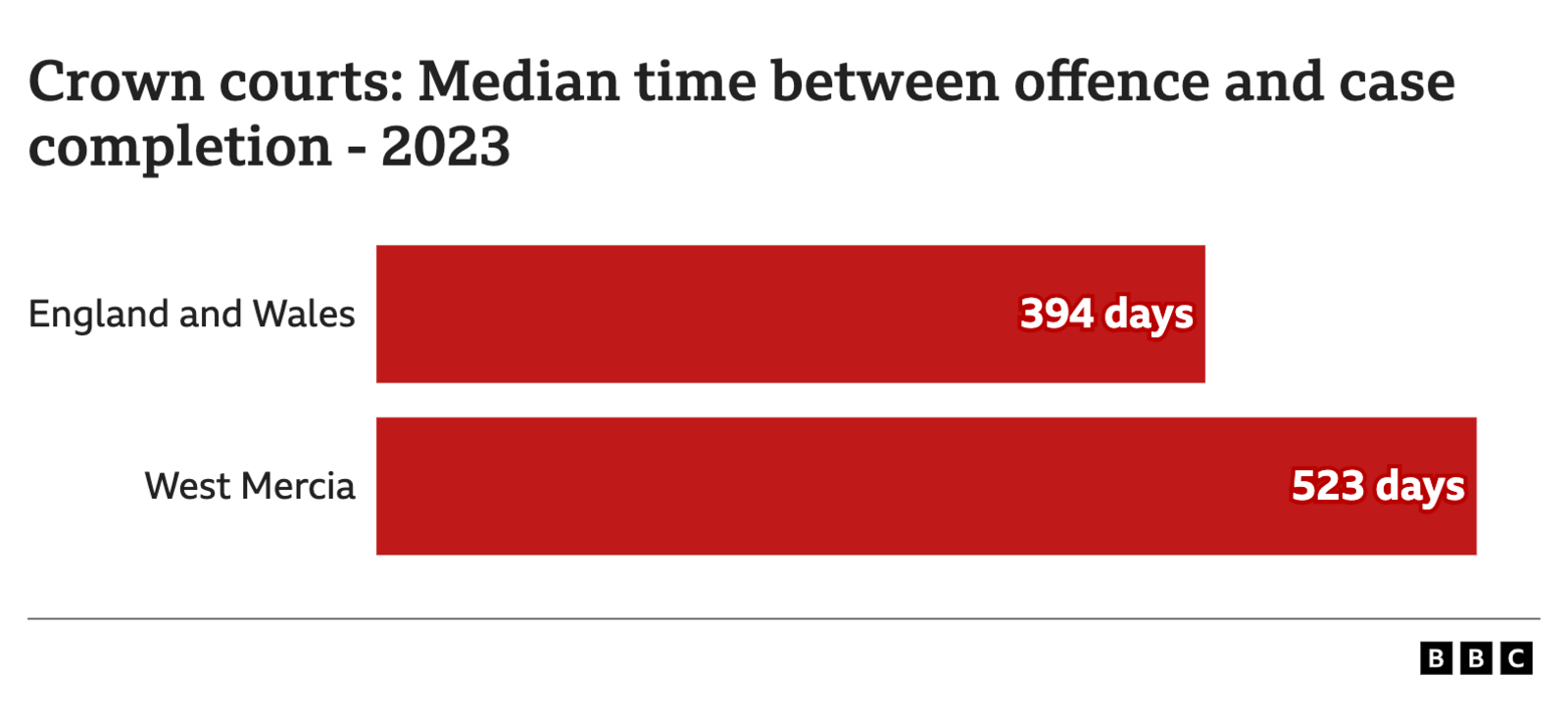

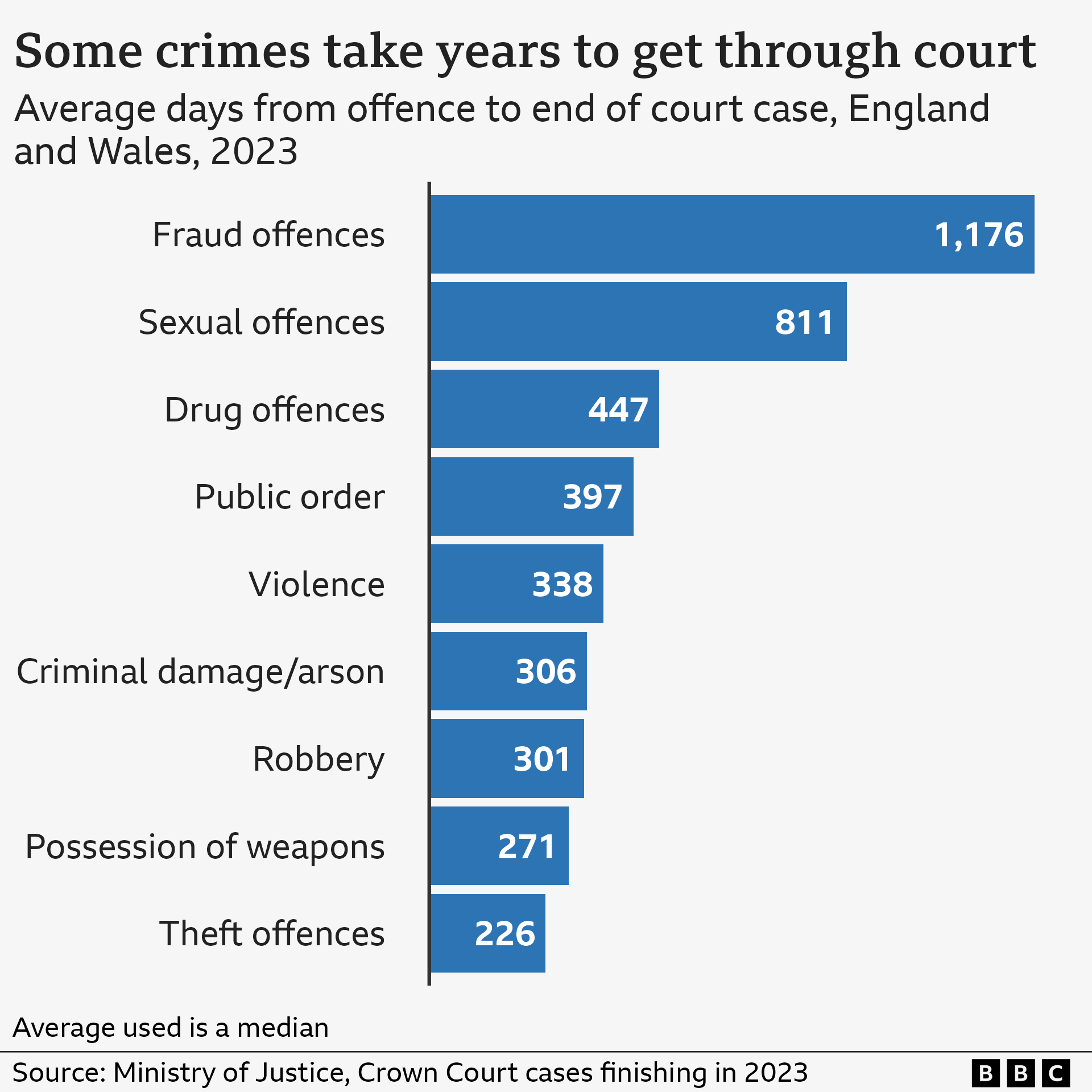

The backlog of Crown Court cases in England and Wales is close to a record high - more than a quarter have now been open for over a year. In one area, on average nearly 18 months pass between an incident occurring and a jury reaching a verdict.

But many people have been waiting a lot longer for justice.

Silkin Way is a 14-mile walking route that snakes its way through much of Telford. On 25 January 2018, there was an altercation on the path between four males, and a few days later three teenagers were charged with grievous bodily harm.

Telford magistrates sent the case to be heard at Shrewsbury Crown Court, because of its seriousness, and a trial was fixed for September 2019.

A problem at the court meant it had to be rescheduled for November 2020, but again the court couldn’t fit the case in. An effort to hear the case in February 2022 also failed.

A new trial was then set for November 2022. Further problems with court availability, however, meant the case was once more delayed, until last month, April 2024.

Then on the day the six-day trial was due to begin, the court removed it from its listings, as an existing trial had overrun - Shrewsbury didn’t have the capacity for both trials to take place simultaneously.

A new trial has now been set for January 2025, seven years after the incident on Silkin Way.

“Even if I’d been found guilty, it would have been better than what I'm subjected to now,” says Lewis Harborn, one of the three accused, who, like the others, has pleaded not guilty and maintains he is innocent of any wrongdoing.

“I would have rather just got locked up - even if it’s for something I've not done - get out and start my life again, than be seven years on thinking, ‘Is it going to happen?’”

Lewis Harborn says even a guilty verdict would have been better than his years-long wait for a trial

Now 24, he says he has been to court 16 or 17 times over the years. He had a mental breakdown because of the strain, he says, but is now a fully qualified truck mechanic and workshop foreman.

If convicted, the three accused could still face seven-year prison sentences.

Lewis Harborn points out, however, that if the original 2019 trial had gone ahead, and even if he had been found guilty and imprisoned, then he would most likely have been out in 2022 or 2023 and would have been able to put it behind him.

He says that people are not sympathetic when he expresses his frustration about the delays.

“If you try and talk about this sort of situation, people tend to just judge you straight away, think you're a bit of a wrong ‘un,” he says, adding that it often seems pointless to make any plans for the future.

In brief comments to the BBC, the alleged victim of this incident said he felt he had been “pushed aside to just deal with it on my own with no support or anything. I just feel like the system is failing”.

Polling suggests that most people think public services have deteriorated nationally in recent years. This article is the second of three focusing on the town of Telford, which a BBC News analysis has identified as facing particular challenges across its courts, schools and health services. Similar problems to those found in Telford are widespread, however.

The delays in the courts system are one of a number of problems in the criminal justice system.

Prisons are full, so some inmates are being released early while trials are being deliberately delayed to ease the pressure on jails.

To cope with the backlog at Shrewsbury Crown Court, the Ministry of Justice has created an additional courtroom at Telford Magistrates’ Court.

Cases listed for Court 4 at Shrewsbury Crown Court are now physically heard 14 miles away in Court 1 at Telford.

The West Mercia region covers Telford, the rest of Shropshire, plus Herefordshire and Worcestershire

During a recent visit I made, a recorder from Manchester, a part-time judge, was hearing a case about alleged sex abuse within a family, which had finally come to court after being reported in 2019.

The passage of time contributed to several witnesses responding with “I can’t remember” to many of the barristers’ questions.

Breaks in the trial had to last a minimum of 20 minutes, said the judge, as the building, a magistrates’ court, wasn’t set up to handle jury cases.

Jurors had to be escorted across two car parks and up two flights of stairs to get to the jury room.

Though proceedings were nominally due to start at 10:00 and 14:00 each day, in reality the trial would resume up to an hour late, as the court tried to squeeze in other cases.

One defendant failed to show up as he had not realised his hearing was in Telford rather than in Shrewsbury.

Another geographical mix-up saw the judge in Telford hearing a case online with the defendant and barristers sitting in a courtroom in Shrewsbury.

A hearing in another case presided over by the same judge - concerning a man accused of threatening someone with a knife - was delayed as the prosecuting barrister failed to show up.

An enterprising lawyer from the Crown Prosecution Service scurried out of court and returned minutes later with the barrister prosecuting the sexual abuse trial.

He walked into court saying, “I literally have no idea what this case is about. I’ve not had any opportunity to read anything beyond the indictment.”

The defence barrister proceeded to brief him on the case. When the judge then turned to the prosecuting barrister and asked him to confirm whether the indictment was correct, the barrister replied: “I can’t say one way or the other.”

The case has now been listed for trial in December.

Criminal lawyer Steven Meredith says many people are leaving the legal profession

“The system is broken,” says Steven Meredith, a criminal lawyer at WMB Law in Telford. “I don’t believe there's enough judges. I don't believe there's enough courtrooms.

A lot of the magistrates’ courts were closed a number of years ago. There's a lot of people leaving the profession, the pressure is too high. And it's [because of] cost-cutting, in my opinion.”

Delays were increasing at crown courts before the pandemic but the backlog now stands at more than 67,500 cases across England and Wales according to the latest official data.

The number of days in which Shrewsbury Crown Court was sitting decreased by 18% between 2016-17 and 2019-20, part of a nationwide effort by the Ministry of Justice to cut costs.

A Ministry of Justice spokesman said crown courts had sat for over 107,000 days in the past financial year, the highest number in seven years.

BBC analysis of government data shows on average, it takes 17 months between an offence being committed and a crown court closing a case in the West Mercia area - which covers Telford, the rest of Shropshire, plus Herefordshire and Worcestershire.

That is the third longest in England and Wales, after central London and Hertfordshire.

The problem has been exacerbated as one of the courts in the area, Hereford Crown Court, has been closed since June 2020, when the roof fell in. Cases have therefore had to be moved to other parts of West Mercia, or the wider West Midlands.

The number of outstanding cases in the area stood at 1,362 at the end of December 2023, 92% higher than in December 2019. Over the same period, the England total increased by 78%.

Several lawyers, victims and defendants living in the Telford area told the BBC of delays lasting years

The constant delays and adjournments mean that West Mercia Police’s Witness Care Unit - the team that deals with people giving evidence, such as eyewitnesses, police officers or court experts - now has 26,000 people on its books, double the figure before the pandemic.

Despite the increase in Shrewsbury Crown Court’s sitting days, several lawyers, victims and defendants have told the BBC in recent weeks of delays lasting years.

Here are three examples:

One man was charged with possession of an imitation firearm in 2019. After several attempts to start the trial, the case was finally dismissed last month, because the main witnesses failed to attend court

A man charged with fraud in 2019 will not have his case heard until 2025. In the meantime he cannot get divorced, as he doesn’t know what sort of financial settlement he can reach with his wife

A drug dealer, found in possession of heroin and crack cocaine, was given a suspended sentence after it took four years to bring his case to court. The judge said he would have received a two-year prison sentence if his case had been handled promptly

One of the largest backlogs, however, appears to involve rapes and sexual assault cases.

BBC News has heard from numerous complainants who have been waiting years for justice.

“Our justice system is in crisis,” says Becky Jones, chief executive of Axis Counselling, which provides support to victims of sexual abuse.

Complainants about to appear in court have to review the video of the original interview they gave police, but often, she says, they find out a couple of days before they are due to attend, or even on the day itself, that the trial has been adjourned and relisted for another time.

“And this happens again and again and again. We have seen our clients face up to six adjournments spanning more than two years, where each time they must do all the preparation, only to be let down by the system again.”

The delays, Ms Jones says, compound the impact of the abuse, affecting survivors’ mental health and family relationships.

“The continued delays in the criminal justice system can prevent them from moving on with their lives. Survivors’ experiences of the criminal justice system have been described by some as like being raped all over again.”

In Emma’s case (not her real name), the delays were exacerbated by errors.

After she reported a case of historical sexual abuse in 2019, the first trial, due at Worcester Crown Court in 2022, was delayed because of a strike by barristers. It finally began at the end of 2023.

“I knew squarely what I had to do. You have to dig deep, you’ve got to put your armour on,” Emma says.

Standing in the dock was the alleged abuser, waiting for Emma and her sister to give evidence. But within hours, the case was adjourned.

The listings officer had put the trial down for two days rather than the necessary eight, and the judge was not available to hear the case.

“You just need it to happen, you need it to go ahead. I remember going and seeing my sister in the afternoon and I haven't held my sister like that for such a long time. We just sobbed.”

The trial has now been scheduled for February 2025, almost six years after Emma first went to the police.

Additional reporting by Katie Inman, Daniel Wainwright and Callum Thomson

Related topics

More from Michael Buchanan in Telford:

- Published11 June 2024

- Published9 June 2024