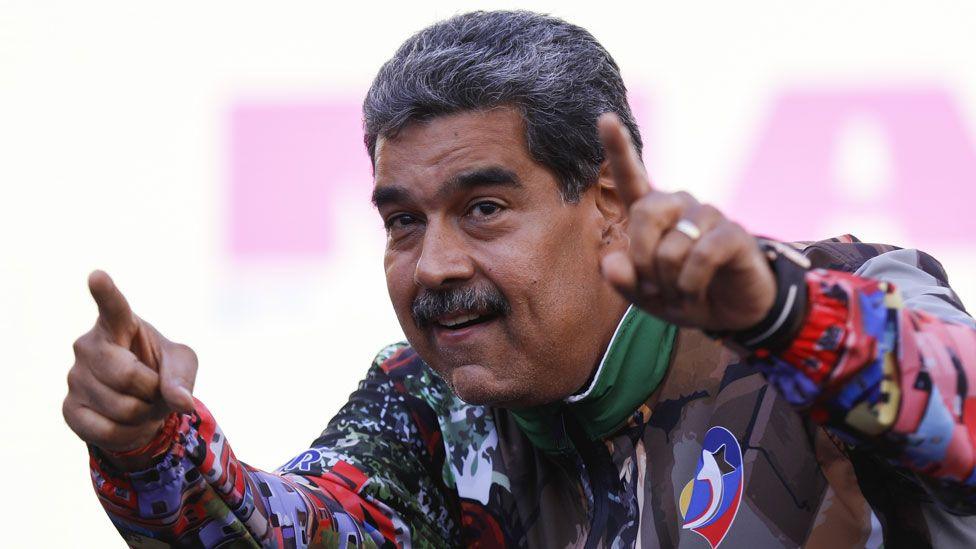

Nicolás Maduro: The leader who promised to win 'by hook or by crook'

- Published

When President Nicolás Maduro took to the stage on 4 February this year to mark the anniversary of the failed 1992 coup led by his mentor, Hugo Chávez, his rhetoric was always going to be fiery.

The fourth of February is the day when followers of Chavismo, the political movement created by Chávez, celebrate their late leader.

Speaking to a loyal crowd of Chavistas dressed in their traditional red T-shirts, Mr Maduro urged them to show "nerves of steel" ahead of this July's presidential election.

On 4 February, Nicolás Maduro said his party would win "by hook or by crook"

He had good reason to do so. Last October, 2.4 million Venezuelans cast their vote in a primary organised by a coalition of opposition parties.

It was won by María Corina Machado with 93% of the vote.

Ms Machado has since become Mr Maduro's most formidable opponent, managing what had eluded others before her - to unite the notoriously divided Venezuelan opposition behind one leader.

During his 11 years in power, Mr Maduro has managed to run rings around the opposition time and time again, aided by the fact that opposition leaders often seemed to spend more time attacking each other than concentrating on beating him.

And maybe it was that nervousness which led Mr Maduro not just to predict a victory in the upcoming election - something many candidates do - but to add that he would win "by hook or by crook".

To opposition activists who have long bemoaned being the victims of government harassment, the president's remark came as no surprise.

After it had been widely reported, Mr Maduro sought to clarify what he had meant, insisting during a TV appearance that his “by hook or by crook” remark had referred not to victory in the election but to his team’s readiness to overcome any “conspiracies” or “any ambush against the Venezuelan people”.

But it is nevertheless a telling slip of the tongue from the leader of a movement which likes to portray itself as representing a mass of Venezuelans, whose loyal support, they argue, has afforded it many an election victory and kept it in power without interruption since 1999.

It is not the first time Mr Maduro's words have raised eyebrows.

His detractors have long made fun of his verbal gaffes and humble beginnings as a bus driver.

But the 61-year-old has used his past to his advantage, cultivating his image as a "man of the people", dancing salsa with his wife during his rambling TV shows and never missing an occasion to whack a baseball, throw a basketball or spar with a boxer.

And while he never achieved the popularity among Chavistas that his predecessor Hugo Chávez had, he has so far managed to remain the movement's uncontested leader.

This was far from a given when he was picked by Hugo Chávez in 2012 as his heir after the latter was diagnosed with cancer.

Many had thought Chávez would choose Diosdado Cabello, a fiery and combative military man, for the role of acting president while the ailing leader was receiving treatment in Cuba.

But Chávez instead anointed Mr Maduro, whom he had just named vice-president after serving six years as Chávez's foreign minister.

Following Chávez's death in March 2013, Mr Maduro narrowly won the election the president's death had triggered, defeating opposition candidate Henrique Capriles by 1.6 percentage points - a result Mr Capriles disputed.

In 2018, Mr Maduro sailed to victory by a wide margin in elections which were roundly dismissed as neither free nor fair.

The main opposition coalition had decided to boycott the polls after a raft of candidates were arrested or had fled the country, leaving the field virtually empty for Mr Maduro.

Arguably, one of Mr Maduro's main achievements has been how he has managed over the past 11 years not only to prevent any challenges to his rule within his PSUV party, but also to form strong alliances with those who have backed him.

His defence minister, Vladimir Padrino, has been in the post for almost a decade, ensuring that the armed forces remain behind him.

The support of the armed forces was key when the then leader of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared himself the rightful president in January 2019, arguing that Mr Maduro's re-election in 2018 had been fraudulent.

The hope of the opposition that Mr Guaidó would replace Mr Maduro in the presidential palace was soon quashed, with all the major institutions remaining under the firm control of the government.

Allies of Mr Maduro also control the main electoral body, the Supreme Court and the Attorney-General's office, among others.

Suspicious of outsiders, he surrounds himself with a close-knit group of trusted politicians, whom he rotates through different high-ranking posts.

Among them is Delcy Rodríguez, who has served as his communications minister, his foreign minister and most recently, as his vice-president.

Delcy Rodríguez (left) has been one of the closest allies of Mr Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores (centre)

Her brother Jorge is another close Maduro ally, who currently heads the government-controlled National Assembly.

Mr Maduro and some in his inner circle - including his defence minister - have been further welded together by being charged by the US authorities in 2020 with "narco-terrorism" and drug trafficking.

The president used the indictment to portray himself as a fighter against "US imperialist forces", which he claims are targeting him because he "stands up for the people".

He also blames US sanctions for the dire economic crisis which Venezuela has suffered under his leadership.

Almost eight million Venezuelans have left the country over the past decade, driven out by a combination of widespread shortages and increasing political repression.

To stop the economy's freefall, in 2019 Mr Maduro relaxed some of the strict foreign currency regulations brought in by Chávez.

Shortages have eased since then, but those without access to foreign currency continue to struggle.

Opinion polls suggest Mr Maduro's popularity has plummeted over the years, in large part because of the economic downturn he has presided over.

Nevertheless, his socialist PSUV party can still draw on a hard core of supporters, as well as a considerable number of people who have benefited financially from his rule.

Maduro's PSUV party has a hard core of committed supporters

His government's actions in recent months, however, appear to betray his worry that his powerful party machine may not be able to win the election if the vote is free and fair.

First, the comptroller-general, a government ally, banned his foremost rival, María Corina Machado, from running for office - a decision which was later confirmed by the government-controlled Supreme Court.

Then, the woman whom the opposition coalition had chosen to replace her on the ballot was prevented from registering.

Finally, a relatively unknown former diplomat, Edmundo González, was confirmed as the opposition coalition's unity candidate in April.

Mr González has sailed past Mr Maduro in the opinion polls in record time, with some giving the 74-year-old a lead of 40% over the president.

In response, Mr Maduro's rhetoric has become more belligerent, even evoking the risk of a "civil war" should he lose.

“If you don't want a bloodbath in Venezuela, a civil war brought about by the fascists, then let's strive for the biggest success, the biggest victory in the electoral history of our people," he told voters less than two weeks before the election.

Invoking a bloodbath may seem extreme, but Mr Maduro has much to lose, were he to be defeated at the polls.

Not only has the US offered a $15m reward (£11.6m) for his capture on "narco-terrorism" charges, but he is also under investigation at the International Criminal Court for alleged crimes against humanity committed by the security forces during the crackdown on a wave of anti-government protests in 2017.

No one should be surprised if, faced with an election defeat, the former bus driver refuses to accept that he has reached the end of the line.

Many fear he will not go quietly.

Update 21st November: This article has been updated to explain that in a subsequent TV appearance President Maduro denied that his “by hook or by crook” remark was referring to victory in the election.