'I could have lost my child' after flawed DNA test

Unreliable DNA tests have turned lives upside down

- Published

A woman who received flawed DNA test results identifying the wrong man as her unborn baby's father has told the BBC the mistake could have led to her losing custody of her child.

'Sarah' - not her real name - lives in the West Midlands but is one of dozens of people claiming to be victims of unreliable tests advertised online and processed by a lab in Canada.

She said there was a point during the legal battle when her child's biological father was seeking full custody, adding: "The fact that I could’ve lost my child over it was big, very big."

The company, now trading under the name Accu-metrics, has not responded to BBC requests for comment.

When Sarah discovered she was pregnant in 2019, she faced a dilemma.

"At that time, I was seeing two men," she said. "I was engaged and I was having an affair, so I didn’t know who the father was."

Seeking reassurance, she searched online for prenatal paternity tests and found a company based in Canada which had a UK website and phone number.

It offered a blood test costing £350, which promised to confirm the paternity of her unborn child.

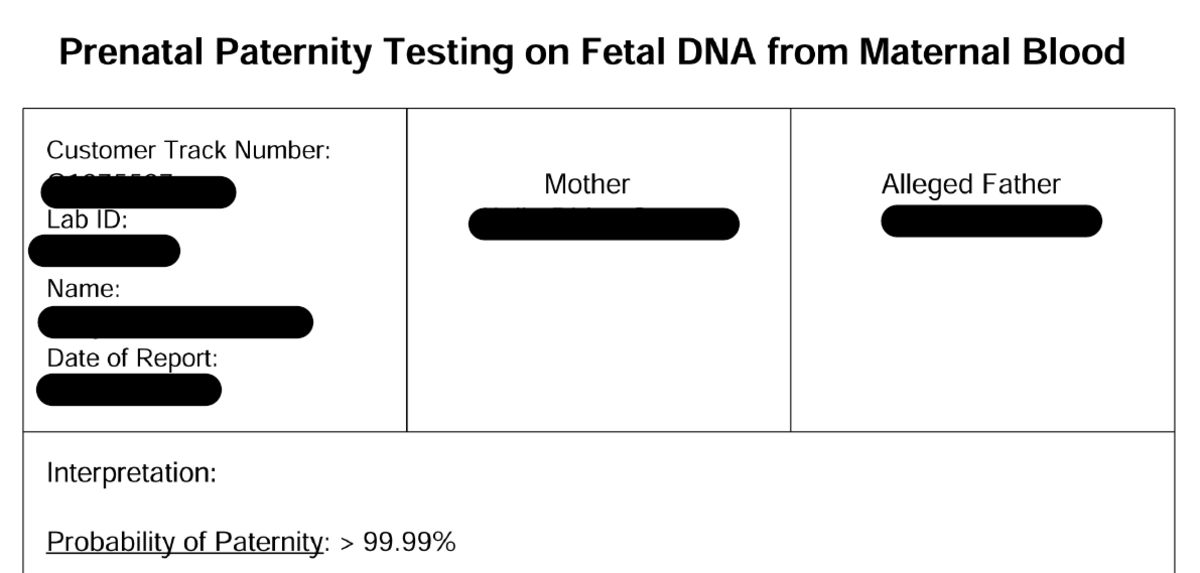

The original DNA test result, which was later found to be inaccurate

Sarah, who is in her thirties, said: "They advised that it was non-invasive and they'd be able to tell me as early as seven weeks pregnant, and it was 99.9% accurate and it wouldn't harm me or anyone else involved, or the baby, which was the most important part.

"They sold me everything really, they told me everything I wanted.

"I was so worried and not in a good state mentally. They were my golden ticket to finding what I needed to know."

Sarah and her fiance used a home-testing kit to obtain samples of their blood via a finger prick tool and posted the samples off as instructed.

When the results came back, they confirmed the baby was her fiance's.

"I think there was a relief, because it was the answer that I wanted. But no matter the result, this was a child I was going to bring into this world," Sarah said.

However, after the baby's birth, a second DNA test - using a UK-based company - was requested by the man involved in the affair.

The results showed he was the biological father, not Sarah's fiance.

She said: "It's been life-changing, completely life-changing and it totally messes with the logistics of life, I guess, because there's another person to consider."

Sarah, who has since married her fiance, was involved in a lengthy legal dispute over custody. The courts ruled it must be shared with her child's biological father.

Describing the situation as "difficult", she said: "We’re not on speaking terms, we don't talk, so we have to be able to figure out how our lives work around all of that and I'm hoping through time, eventually, it becomes easier."

Who regulates testing services?

Earlier this year, an investigation, external by Canadian broadcaster CBC News found a number of customers had been given incorrect results by the company Sarah had used for the first test.

CBC News reported that the company knew the tests were unreliable and yet continued selling them, routinely identifying the wrong biological fathers.

The Canadian government's Department of Health said companies or laboratories offering genetic testing services were not regulated by Health Canada.

It said: "They are regulated under provincial or territorial jurisdictions, as those governments are responsible for the delivery and administration of healthcare services, including laboratory services."

The BBC approached Ontario Ministry of Health but it said its regulatory work in this area related only to laboratories with clinical purposes. It said prenatal paternity testing was not considered a clinical purpose.

Neither organisation could identify who was responsible for regulating the laboratories and companies providing results from genetic test kits, suggesting there may be no regulatory framework in Canada to cover this activity at present.

The Standards Council of Canada, which provides accreditation but is not a regulatory body, said the company - Viaguard Accu-metrics - is no longer accredited by SCC as it did not meet its requirements for accreditation.

Its previous accreditation was only for DNA testing and not all the tests it offers.

Professor Denise Syndercombe-Court said some online firms were not being honest about the reliability of tests

Denise Syndercombe-Court, a professor of forensic genetics at Kings College London, said a blood test was not the most reliable method of establishing paternity before a child was born.

She said it was best to carry out tests after birth but if a prenatal test was wanted, an invasive test was more reliable.

Prof Syndercombe-Court said the best methods for determining paternity before birth were an amniocentesis test, which involves extracting a small sample of amniotic fluid, or chorionic villus sampling during which a small sample of cells from the placenta are removed and tested.

Both tests carry a small risk of miscarriage, meaning some people opt for less reliable non-invasive methods.

"Online, people are not telling you how reliable [blood testing] is," Prof Syndercombe-Court said.

"I have seen one company that says they are 100% accurate and I know they're not."

Years later, Sarah is trying to move on with her life but said it was "terrifying" the company she had originally used was still operating.