How stealth tax hits middle earners with high bills

- Published

Scotland's income tax system has been diverging from the rest of the UK, but the behaviour of top earners is a constraint on pushing further.

In common with the rest of the UK, the big tax dragnet is the freezing of thresholds, in which many middle earners are now stealthily caught by higher rate bills.

Lower earners were being taken out of paying income tax, but that has been thrown into reverse. By 2027, the UK personal allowance will have the same real value that it did in 2013.

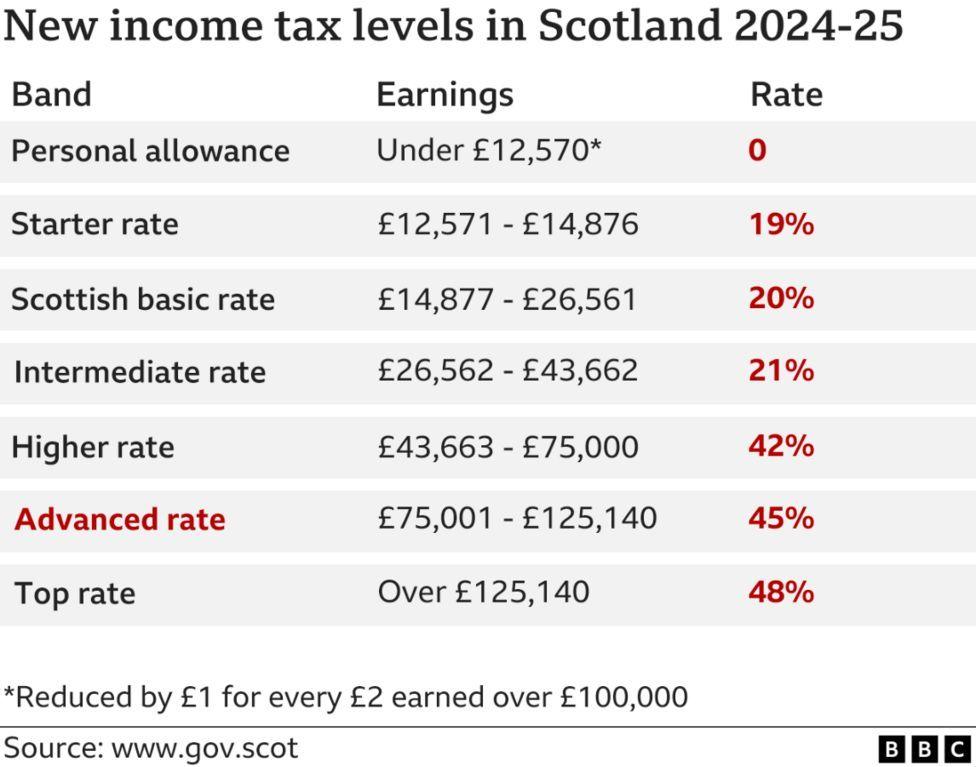

Happy new tax year. With the start of 2024-25 from today, you may be paying a third less National Insurance than you faced this time last year. Or you may be paying more - a higher rate of income tax as your pay goes up, and a lot more if you earn more than £75,000 in Scotland during the new financial year.

If you own a second home in Scotland, you may be facing a doubling of your council tax bill, unless it's in the council areas of Falkirk, Glasgow or North Ayrshire.

And if you run a business from larger premises, you're facing an unwelcome rise in business rates. Retailers are particularly grumpy about that.

The National Insurance cut offsets the income tax rise on higher earning Scots, meaning only those earning above £112,000 face a bigger deduction from their payslip than last financial year.

But the big increase in tax is the stealthy one, of 'fiscal drag'. A couple of years of high price inflation has resulted in high wage inflation. And as people on low earnings have moved above £12,570, they have found themselves starting to pay income tax. That starter threshold, the only bit of income tax in Scotland which is controlled by the UK government, has barely moved while wages have.

The policy last decade, of taking more and more people out of the income tax net, is being reversed, and is likely to take us back to a similar share of workers having to pay income tax. The real value of the starter threshold by 2027 will have returned to its 2013 level.

Many second property owners face a double council tax bill

Tax take

Another painful threshold is at £43,663. Above that, each additional pound earned is taxed at 42 pence, up from the 21 pence tax take on the pounds below.

Called the 'higher rate', this was intended for higher earners, and in 2017, the threshold of £43,000 caught only the top-earning one in every eight taxpayers. While the threshold has gone up by only £663, earnings have risen more steeply. The 'higher rate' (confusingly, it's now the third highest rate in Scotland) now catches more than one in five income tax payers.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission estimates that fiscal drag has raised an extra £320m in Scotland in only two years.

A similar fiscal drag is being applied by the UK Treasury, with a lower rate and a higher threshold. It is deducting tax at 40 pence in the pound for pay and pensions above £50,270. In the seven years to 2027, the Office for Budget Responsibility reckons that drag effect alone will have dragged £43bn more out of taxpayers.

It's a staggeringly big increase in tax take, but one that people are more likely to welcome as it reflects on their earnings going up. Yet that is the element of the tax system that best explains why tax, in all its forms, is taking its biggest bite out of national income since the 1950s.

The UK income tax gap significantly widens from middle earners upwards

Fat cats

At Holyrood, there is pride taken by the Scottish government in having a more progressive income tax system than the rest of the UK. That reflects Scottish values, they say, it's part of a 'social contract' and it helps protect budgets for Scottish public services.

At the lower-earning end of the taxpayer spectrum, there is a very modest £23 or so to be gained. From the median full-time income just below £29,000, Scots are paying more in income tax than people on the same earnings are having to pay in the rest of the UK.

At £50,000, the tax gap for equal pay is more than £1,500 pounds. For a police chief superintendent or head teacher on £100,000 per year, the tax bill is £3300 higher than the same salary south of the Border, and for a senior hospital consultant on £130,000 in pay, the gap is above £5,000.

Take that up to the fat cat salaries of lawyers and accountants in big global partnerships, and a £700,000 pay package faces a tax deduction £22,000 more than a partner on the same pay in London.

Across borders

There are not many such earners in Scotland. Only 40,000 people are expected to be paying the top rate of tax next year - 48 pence deducted from each pound of earnings above £125,140.

That is only 0.9% of taxpayers in Scotland. The same threshold for the top 45% tax rate across the rest of the UK is paid by 2% of taxpayers, and last year, they contributed around 39% of all income tax revenue.

Those on higher or top rate tax in Scotland paid around 65% of all income tax revenue.

That means it's really important that these people continue to pay. But increased divergence of Scottish and UK income tax rates means an increased incentive not to pay the Scottish rate.

The same is true across international boundaries, and between the states of the USA, where people can go to the lowest tax places, but often choose not to. What makes Scotland and the rest of the UK different is the ease with which people can move their taxable income between the two.

The higher income tax rate is a disincentive for filling doctor vacancies in Scotland

NHS vacancies

For those who own businesses, they can take dividends in place of salary. Tax on dividends is paid to the UK Treasury, at UK rates.

There is an incentive to put more money into pension funds to avoid income tax. People can leave Scotland and wealthy people can locate themselves elsewhere for more than half the year.

But probably more significant is the recruitment of people into high-paying Scottish jobs. A top hospital consultant can look for a similar salary in Scotland and England, but with a tax bill in Scotland that is £5000 higher. That's a disincentive for filling vacancies in NHS Scotland.

Is there a reliable measure of how these 'behavioural effects' reduce tax revenue in response to relatively high tax rates? No, it's hard to estimate. But the Scottish Fiscal Commission has the task of doing so, to set the parameters for Scottish government budgets.

It says the increase at the top levels of income tax in the new financial year would bring the Scottish government a gain of around £200m, if there were no such 'behavioural effects'. But when people have adapted to the diverging tax rates, that gain is forecast at only £82m.

The tax system may be more progressive and that may be politically astute, but that estimate of £118m revenue lost is a measure of the diminishing returns from loading tax on to high earners.