Titan sub disaster: Five key questions that remain

The Titan sub was on a trip to see the wreck of the Titanic

- Published

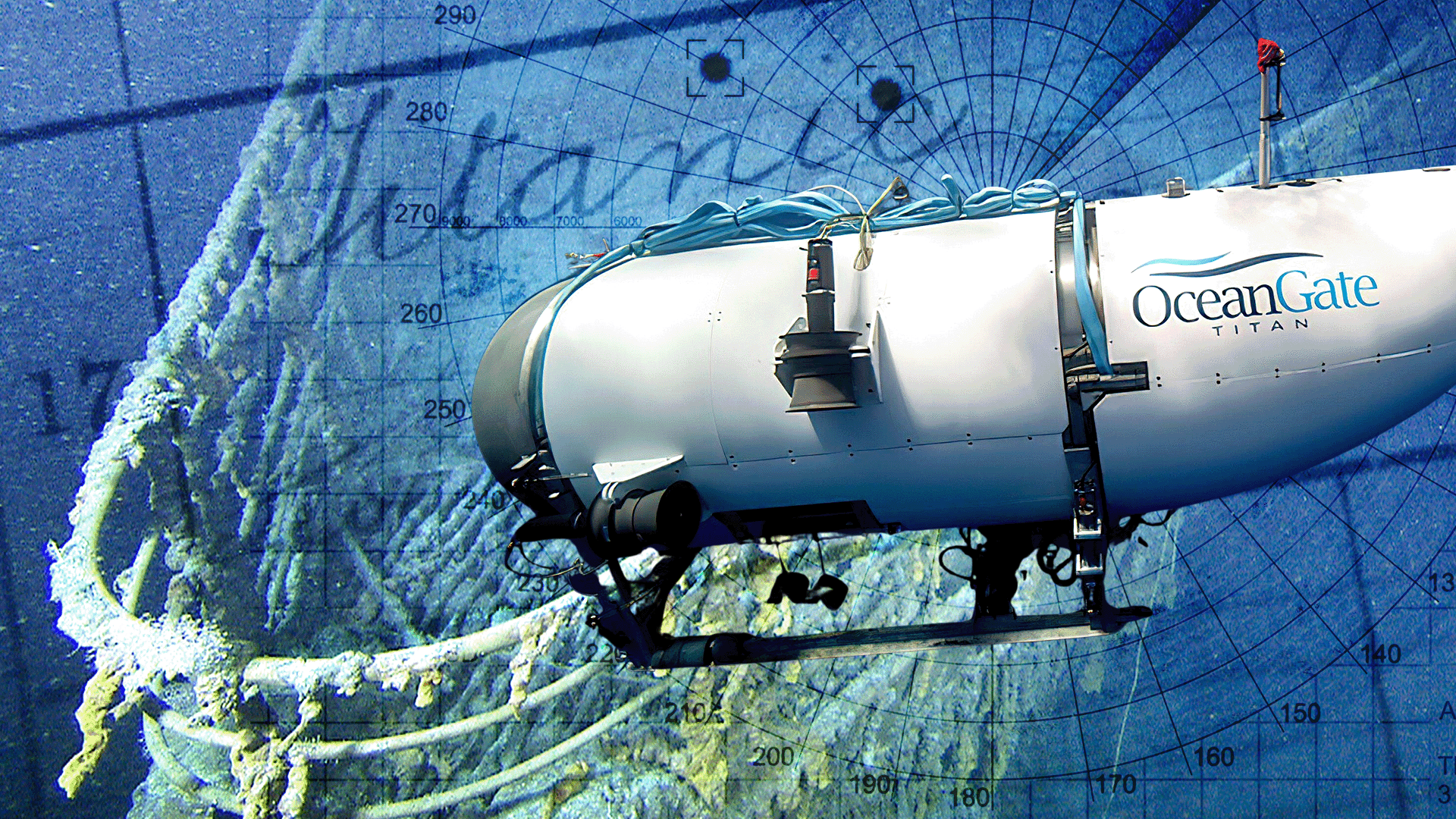

It was the submersible that promised passengers the trip of a lifetime. A chance to descend 3,800m (12,500ft) to the Atlantic depths to visit the wreck of the Titanic.

But last year, a dive by Oceangate’s Titan sub went tragically wrong. The vessel suffered a catastrophic failure as it neared the sea floor, killing all five people onboard.

The US Coast Guard is holding a public hearing on 16 September to examine why the disaster happened, from the sub’s unconventional design to ignored safety warnings and the lack of regulation in the deep.

Titan began its descent beneath the waves on the morning of 18 June 2023.

On board were Oceangate’s CEO Stockton Rush, British explorer Hamish Harding, veteran French diver Paul Henri Nargeolet, the British-Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son Suleman.

Later that day, after the craft failed to resurface, the US Coast Guard was notified, sparking a vast search and rescue operation.

The world watched and waited for news of the missing sub. But on 22 June, wreckage was discovered about 500m (1,600ft) from Titanic’s bow. Titan had imploded just one hour and 45 minutes into the dive.

These are five key questions that still need to be answered.

Clockwise from top left: Stockton Rush, Hamish Harding, Shahzada Dawood and his son Suleman, and Paul-Henri Nargeolet were all onboard the Titan

Did the passengers know the dive was going wrong?

Those on Titan could stay in contact with the support ship, the Polar Prince, with text messages sent through its onboard communications system. The log of these exchanges could reveal if there were any indications that the sub was failing.

The vessel also had an acoustic monitoring device - essentially mics fixed to the sub listening for signs it was buckling or breaking.

“Stockton Rush was convinced that if there was an imminent failure of the submersible, they would get an audio warning on that system,” explains Victor Vescovo, a leading deep sea explorer.

But he said he was highly sceptical that this would have provided enough time for the sub to return to the surface. “The issue is how quickly would that warning happen?”

If there were no apparent problems during the descent and alarms failed to sound, those on board could have been unaware of their imminent fate.

The implosion itself was instantaneous, there would have been no time for the passengers to even register what was happening.

Which part of the Titan sub failed?

Forensic experts have been examining Titan’s wreckage to find the root of the failure.

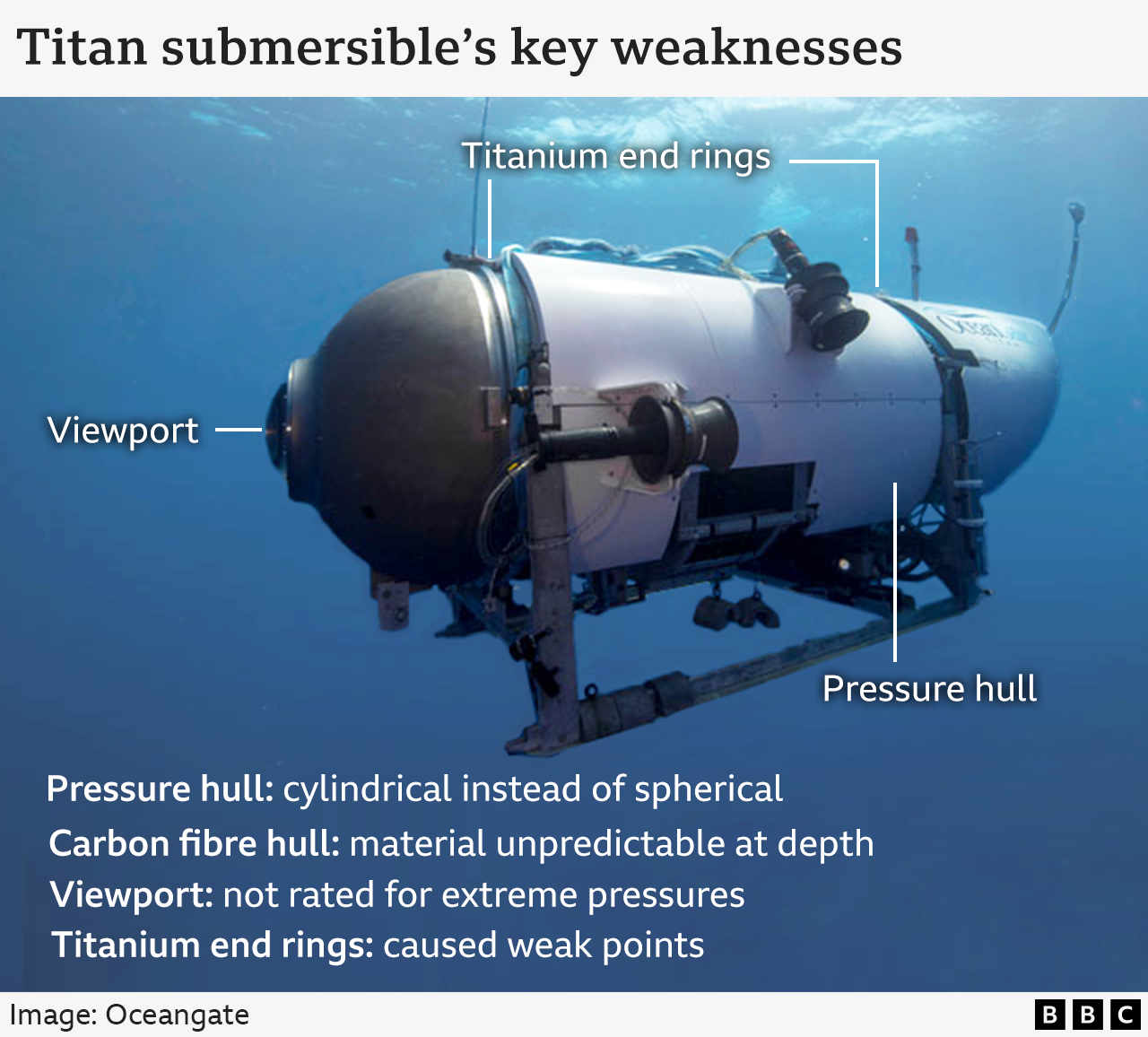

There were several issues with its design.

The viewport window was only rated to a depth of 1,300m (4,300ft) by its manufacturer, but Titan was diving almost three times deeper.

Titan’s hull was also an unusual shape - cylindrical, rather than spherical. Most deep-sea subs have a spherical hull, so the effect of the crushing pressure of the deep is distributed equally.

Watch on BBC iPlayer (UK Only)

Titanic Sub Search

- Attribution

The sub’s hull was also made out of carbon fibre, an unconventional material for a deep-sea vessel.

Metals such as titanium are most commonly used as they are reliable under immense pressures.

“Carbon fibre is considered to be a material that is unpredictable [in the deep ocean],” explains Patrick Lahey, CEO of Triton Submarines, a leading manufacturer.

Every time Titan went down to the Titanic - and it had made multiple dives - the carbon fibre was compressed and damaged.

“It was getting progressively weaker because the fibres were breaking,” he said.

The junctions between different materials also gave cause for concern. The carbon fibre was attached to two rings of titanium, creating weak points.

Patrick Lahey said the commercial sub industry had a longstanding, unblemished safety record.

“The Oceangate contraption was an aberration,” he told BBC News.

Planes and ships spent several days looking for the missing sub

Did ocean sounds distract from the search?

Ships, aircraft and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) were scrambled to the Atlantic to try to find Titan.

A couple of days into the search, there were reports of underwater noises picked up by a search plane’s sonar, raising the possibility they were coming from the sub.

ROVs were sent to locate the source but found nothing.

It is still not clear what the sounds were - the ocean is noisy and even more so during an operation like this.

A more pertinent subsea sound was detected by the US Navy’s sonar system at the time the sub went missing - an acoustic signal consistent with an implosion. The information was only made public on the day the remains of Titan were found.

It is not known when the US Coast Guard was told of the noise - or whether the families and friends waiting on the sub’s support ship were informed.

Eventually the deep-sea robots returned to where Titan had gone missing and the wreckage was found.

Rory Golden, who was on the Oceangate expedition when contact was lost, recently told the BBC those on board the surface vessel experienced four days of fear and “false hope”.

Why were safety concerns ignored by Oceangate?

Many were concerned about Oceangate’s sub.

Victor Vescovo says he was so worried, he had urged several passengers against diving on Titan - including his friend Hamish Harding, one of the five who died.

“I told him, in no uncertain terms, that he should not get in the submersible,” he said.

Fears about safety were also brought directly to Oceangate - including by the company’s former director of marine operations, David Lochridge, who assessed the sub while it was being developed.

Witness to Titan sub tragedy tells of fear and false hope

- Published1 August 2024

Titan sub CEO dismissed safety warnings as 'baseless cries'

- Published23 June 2023

James Cameron: Titan sub company cut corners

- Published23 June 2023

US court documents from 2018, external show that Lochridge had identified numerous “serious safety concerns” and the lack of testing could “subject passengers to potential extreme danger in an experimental submersible”.

Engineers from the Marine Technology Society also said that Oceangate’s experimental approach could result in “negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic)” in a letter shared with Stockton Rush.

In an email exchange shown to BBC News last year, deep-sea specialist Rob McCallum told Rush that the sub should not be used for commercial deep dive operations and was placing passengers in a “dangerous dynamic”.

In response, Rush said he had “grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation” and dismissed warnings that he would kill someone as “baseless”.

With the death of Oceangate’s CEO, we will never be able to ask why he chose not to listen to these concerns. But the public hearings could reveal who else at the company knew about them - and why no action was taken.

Titan sub pictured on a previous dive

Why did the authorities allow Titan to dive?

Deep-sea submersibles can go through an extensive safety assessment carried out by independent, specialist, marine organisations such as the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) or DNV (a global accreditation organisation based in Norway).

Oceangate chose not to put Titan through this process.

The assessment would have confirmed whether the vessel - from its design through to construction, testing and operations - met certain standards.

Most operators opt to have their deep-sea subs certified - but it is not mandatory.

Rush described his sub as “experimental” and, in a blog post in 2019, he argued that certification “slowed down innovation”.

In an email exchange with Rob McCallum, he said he didn’t need a piece of paper to show Titan was safe, and that his own protocols and the “informed consent” of passengers were enough.

The passengers on Titan paid up to $250,000 (£191,135) for a place. They all had to sign a liability waiver.

Oisin Fanning (right) went to see the Titanic in 2022, accompanied by Stockton Rush (left) and PH Nargeoloet (centre)

Irish businessman Oisin Fanning made two dives in Titan in 2022 - the last before the sub’s fatal disaster.

He said the Oceangate team took safety seriously, with extensive briefings before each descent. But it wasn’t made clear to him that Titan had not been certified.

“I would be lying if I said I didn't think there had been something like that done already - that it conformed with certain norms,” he said.

“We all knew that the Titan was experimental. We were very confident, because obviously there'd been a few dives before that, and it seemed to be working well.”

The public hearings will last for two weeks. The hope is the answers it provides could prevent a disaster like this from happening again.